This is the first in a series of reflections on the opportunities and challenges facing the labor movement this year. How can the movement use the momentum of 2023 to keep building power? How should it set its strategic compass? What kinds of organizing can help it navigate our shifting economy and rough political terrain?

We leave our home in the morning, We kiss our children good-bye, While we slave for the bosses, Our children scream and cry.

And when we draw our money,

Our grocery bills to pay,

Not a cent to spend for clothing,

Not a cent to lay away…

It is for our little children,

That seem to us so dear,

But for us nor them, dear workers,

The bosses do not care.

But understand, all workers,

Our union they do fear,

Let’s stand together, workers,

And have a union here.

—Ella May Wiggins, “Mill Mother’s Lament”

Around 2007, I worked at a large Target warehouse in Queens, New York. I clocked in at 7:30 p.m. and left at 5:30 a.m., if I was lucky. I was often unlucky, putting in 14 hours, stacking boxes on pallets, unstuffing boxes, climbing up ladders to reach the highest shelves. The company had made sure we used space efficiently, meaning all the available space from the lowest shelf cranny to the highest. The end result was a flurry of hands and feet moving at a dizzyingly fast pace in a swiftly orchestrated mobilization of labor. From the top of a ladder, as I stuffed Christmas ornaments ahead of the holiday shopping bonanza, I marveled at how we zigzagged across the floor—each of us performing the functions that ensured the store was always stocked, feedback fed into scanners we wielded like the batons of an unseen symphony of working-class conductors in khakis and red T-shirts. We made our labor appear to the would-be customer as a mere conjuring trick, making stacked shelves appear as if by sleight of hand.

The workforce was largely Latino, Black, and West African. The Latino and Black workers came from the Queens neighborhoods of Corona, Elmhurst, Jackson Heights, Jamaica, and LeFrak City. The West Africans came from the Tremont and Kingsbridge sections of the Bronx. One of the lead workers was from the West African country of Togo. He commanded respect from everyone because he always took the extra overtime and helped other workers by slipping them pain pills or an energy drink when their bodies crashed. I remember him always wearing an orange lifting belt for back support as he zipped around the warehouse floor in a forklift.

At the time, I had another job at a lounge restaurant in the Astoria neighborhood of Queens, not far from William Cullen Bryant, the public high school that I had graduated from a few years earlier, before enrolling at LaGuardia Community College, a two-year school made up of converted factory buildings that educates the city’s working-class majority who speak 97 languages. My cousin and I worked for a cleaning company that paid us off the books and misclassified us as independent contractors. On a typical day, I’d get on my knees and scrape gum from the floor with a spatula. My cousin would stand on a ladder dusting the spider webs off the light fixtures. While I lifted the chairs onto the tables inside, he dragged the bar mats outside, hosed all the bottle caps off, and laid the mats to dry against a parking-lot fence. The workforce was largely Latinos, with Colombians as waiters, Mexicans as dishwashers and busboys, and Dominicans as the clean-up crew. The owners and managers were Greek.

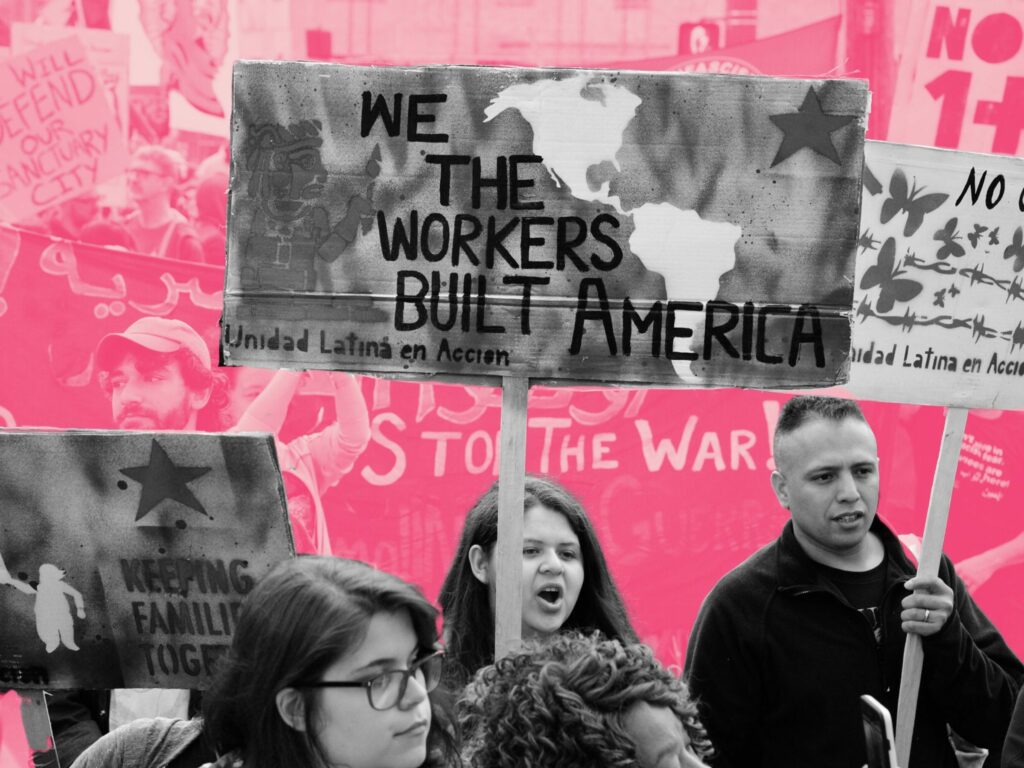

When I think about challenges the labor movement will face in 2024 and beyond, I return to these experiences to grapple with a question and issue an exhortation, bending the question of how we build mass, independent working-class organization in unions and communities into an exclamation point. My twin concerns—working-class organization and stopping the rise of a consolidated far-right movement—revolve on the hope of building a powerful multiracial working-class movement.

We need a multiracial working-class movement, which brings together all who toil in grinding poverty for a shitty paycheck while barely affording high rents, childcare, healthcare, and groceries, because the bosses have all the power, and they maintain it by keeping us divided by differences. They seek to instill fear in us because they want to immobilize us, lest we come together and topple their social hierarchies, replacing them with bonds of solidarity and equality. They confuse us by claiming systems of oppression are natural, like the air we breathe. We are pinched between state violence and obscene wealth accumulation at the top and misery and despair at the bottom.

There is money for the masters of war in Israel, money to fund death machines abroad and police repression on our streets. The belts tighten at state and federal levels when we demand money to repair the crumbling infrastructure of our schools, debt forgiveness for students saddled with crushing debt loads, stable housing for homeless people across the country, asylum for those fleeing violence, and reproductive health access.

In 2022, the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health eliminated the constitutional right to an abortion; the ruling fell hardest on those least likely to have resources to travel for care. The US has the highest maternal mortality rate among wealthy nations. Meanwhile, billionaires are bankrolling anti-transgender advocacy groups, fueling violent attacks against transgender and gender non-conforming people.

To make their billionaire economy and society ours again, we need to take back the power.

The independent organizations necessary to wield power and defeat the Far Right must be rooted in neighborhoods and workplaces. The primary locus must be at the point of production on the job, beginning with the class power that flows from strategic locations in key industries. The second needs to be in mass neighborhood organizations that can act as tribunes for a working class drawing together to face off against the bosses and scab politicians like Donald Trump. We are poor because they are rich. We don’t have health care because they buy the politicians who make the laws. They put company men in elected office to rule us not only at work but in society. They hurt us from on high and on the shop floor. But their social distance from us doesn’t diminish our anguish; it only grows our yearning for a better tomorrow. That’s why we must stand together because an injury to one is an injury to all.

Our solidarity doesn’t take root and grow unless we rub elbows with each other in the same institutions we help co-create, from working-class sports clubs to labor unions.

On the job

While the percentage of workers belonging to a union continues to decline, last year’s uptick in union membership was driven by workers of color and young people. Black workers, whose 13% unionization rate is the highest of any major ethnic or racial group, accounted for the entire numerical increase, according to a January report from the Economic Policy Institute.

Millions of Black and Latino workers toil at nonunion jobs in the logistics sector, at Target, Walmart, and Amazon. Amazon has clustered its facilities in metropolitan areas, so workers can flit more easily in and out of delivery stations to reach customers more quickly. These tight supply chains were central to the Amazon Labor Union’s successful union drive at the company’s fulfillment center on Staten Island, New York in 2022, argued logistics experts Charmaine Chua and Spencer Cox in The Socialist Register last year.

“Any product that moves now, anybody who moves, goes through more connections in chains and networks than a generation ago,” said the historian John Womack in a long interview in the collection Labor Power and Strategy. He described a production process made up of “a series of intermediate and intermittent links in the chain, the steps between the fixed stations of transformation.”

The millions of workers at those links—Amazon Flex drivers; warehouse workers in fulfillment, sorting, and delivery centers; and the delivery service partners (DSPs) Amazon hires through nominally third-party employers to deliver packages—have a patchwork of different employment relationships. These numbers grow even larger if you include Target and Walmart, which are now experimenting with on-demand employment arrangements, meaning hiring workers for short blocks of time without paying them any of the benefits full-time employees get. The task of organizing the unorganized must begin with these low-wage workers of color and others at vulnerable points of the supply chain, where they can choke off the flow of commodities with strike action.

These aren’t the only opportunities for new organizing, but they are the most obvious, if challenging, ones. Other notable efforts include the Communications Workers of America’s push to organize call-center workers in the South, and the United Auto Workers’ ambitious goal of supporting workers launching union drives across the nonunion auto and battery plant sector, especially in the South. Another is the potential for the Teamsters to organize Costco stores nationwide.

In community

Though a serially truant high school student, I became a teacher myself, teaching ESL classes to immigrant workers around 2006 at the community organization, New Immigrant Community Empowerment in Jackson Heights, Queens. That was also the year of massive immigrant marches to defeat legislation that would have made being an undocumented immigrant a crime. Using a popular education approach, I taught English to day laborers who spoke only Spanish. We talked about wage theft and navigating the subway system instead of the typical stuff at language learning centers, which wasn’t part of their lives, such as conversational prompts about visiting Paris.

In 2008, a high-profile raid in Pottsville, Iowa, created a climate of fear across immigrant communities. The raid was part of Operation Endgame, launched in 2003, designed to deport 11 million undocumented people by 2012. My home became a base of operations for the defensive counterattack. Instead of Black Hawk helicopters, bulletproof vests, and other military gear, we had markers, flyers, and a table to sit around and talk. Once my mom, who worked in a paper mill in the Long Island town of Bay Shore that had unionized with the Steelworkers, left for her overnight 12-hour shift at 2 p.m., my former students huddled together and began planting seeds of Jornaleros Unidos (Day Laborers United), the rank-and-file organization that replaced the No-Raids Committee, built with the support of socialists.

Since then, most independent organization of immigrant workers has taken the form of mutual aid groups and loose networks. Most of the institutional expression of organizing among immigrant Latino workers, however, has been through top-down, staff-driven nonprofits. With the possibility of another Trump term in the White House, these organizations are largely ill-equipped to mount the kinds of disruptive mass actions necessary to upset the status quo. They function as social-service providers, and political organizations get drawn in by funding to the Democratic Party’s get-out-the-vote apparatus. There are important exceptions that engage in organizing and power-building, from Desis Rising Up and Moving in Queens to Arise Chicago to the Workers’ Justice Project in Brooklyn, but they are exceptions that prove the rule.

Unions, even those that display labor militancy, have varying responses to today’s fascist threat. The Teamsters’ political arm donated $45,000 to both the Republican and Democratic National Committee funds. At the union’s national headquarters, after speaking with its President Sean O’Brien on January 31, Trump put a target on migrants by saying, “They come from jails and prisons…mental institutions and insane asylums, and they’re terrorists.” Standing in front of a Teamster flag, he then menacingly tied people seeking asylum to the job security of union members, tapping the nativism that has historically soiled the labor movement: “The unions and the Teamsters, if they don’t have [the southern border] closed down, they’re not gonna exist.”

“The Teamsters union supports immigrant workers because we all come from people that came from different countries,” said O’Brien after Trump spoke. Challenging Trump’s nativism was important, but offering him a platform to spew his venom was an abdication of trade union principles masquerading as a democratic process. The real dynamic is one of accelerating class dealignment in which “mechanics and truck drivers give to Trump, while professors and scientists support Biden.”

That’s not the fault of the leaders at the helm of the Teamsters. It’s about understanding the true social base of a Democratic Party “that wins 60 percent support from the wealthiest 10 percent of the country and 75 percent support from top earners in business and finance,” argues the historian Matt Karp. But even if a transformation of class power won’t come from the Democrats, at least their reforms, including saving the pensions of 350,000 Teamsters, create a terrain of struggle for the labor movement and the Left.

Rubbing elbows with Trump twice to curry favor with right-wing members or hedge the union’s bets in case the former president is re-elected is a missed opportunity for political education. Trump is Scabby incarnate, minus beady eyes and sharp teeth, looming over the labor movement, with a blow-dried shrub of hair and the toasty tan of a boss splayed on a beach somewhere we’ll never afford to visit.

Whatever the union’s internal polling says about the number of rank-and-file Teamsters who support the former president—the rest of the electorate is also gradually moving towards the right—Trump’s record is one of successfully mounting a one-sided war against the working class. He used the courts and federal agencies— stacked with the enemies of working people, from pro-corporate lawyers to union-busters dressed up in the robes of judges and the suits of CEOs— to cut off millions of workers from overtime pay and make their jobs unsafe. Bosses laughed all the way to the bank, giving themselves tax cuts, while workers got robbed of their tips and wages.

The tally is clear: “Donald Trump is a scab. Donald Trump is a billionaire and that is who he represents,” said UAW President Shawn Fain, announcing the union’s endorsement of President Biden, who is facing opposition within his party for providing Israel military aid and political cover as it carries out a genocide against Palestinians living under apartheid and occupation. “If Donald Trump ever worked in an auto plant, he wouldn’t be a UAW member, he would be a company man trying to squeeze the American worker.”

Any effective movement to defeat the fascist Far Right must include fighting unions, and the rural white workers, immigrant workers and other oppressed groups within them, building their own durable, pro-worker mass organizations from the bottom up.

Fusing unions and community

In the 1930s and 1960s, the labor and civil rights movements learned how to build mass organizations. In his book I’ve Got the Light of Freedom, the historian Charles Payne talked about how organizers brought together Southern teachers, preachers, beauty-salon workers, and idealistic white students from the North, social worlds colliding and reshaping each other. Civil rights organizers Ella Baker and Bob Moses have many lessons to teach us today about how to join righteous anger with strategy and humility, so the vehemence of our conviction doesn’t burn so hot it obliterates our capacity to reach beyond its orb of flaming passion.

“Organizers had to be morale boosters, teachers, welfare agents, transportation coordinators, canvassers, public speakers, negotiators, lawyers, all while communicating with people ranging from illiterate sharecroppers to well-off professionals and while enduring harassment from agents of the law and listening with one ear for the threats of violence,” Payne wrote. This isn’t a world of abstractions but of juggling many different roles to meet people where they are at.

In the 1920s, William Z. Foster, the radical labor organizer, argued that the left must do the work of organizing the unorganized. “The left wing militantly lead, the progressives mildly support, and the right wing oppose,” he summarized. He called for establishing workers’ clubs and fraternal organizations to generate a left-wing culture. In meatpacking, after World War I, he was prescient to hire Slavic organizers in the Chicago stockyards and African Americans when the company bosses tried to use workers coming North from the South to break strikes. That’s a practical dimension absent from today’s debates about diversity and inclusion, which are largely moral arguments divorced from any socialist vision of a unified and multifaceted working class.

We have to be ruthlessly materialist. We can learn from the example of the late political activist and intellectual Mike Davis.

“What distinguished Davis perhaps above all else was his insistence that, while the social world could be—and ultimately had to be—grasped as a unified totality, this totality could at the same time only be understood as a complex system of differentiated parts, each of which in turn had to be comprehended in its own specificity. It is not enough to say ‘worker’; Davis would then want to know what industry and how it is organized, what skills, living in what neighborhood, worshiping in what religion, participating in what organizations, shaped by what racial and ethnic formations. In this way he showed what it means to make good on Marx’s methodological point, ‘The concrete is concrete because it is the concentration of many determinations, hence unity of the diverse. It appears in the process of thinking, therefore, as a process of concentration, as a result, not as a point of departure.’”

—Historian Gabriel Winant, 2023

We must bring that same rigor to the most important tasks for socialists and anyone else fighting for transformative change today: Building independent class organizations, from caucuses in established unions to serve as the alternative political party within the union bureaucracy, to organizations of self-defense and mutual aid in the community. From that political independence will spring many opportunities to forge stronger solidarities and create new political horizons where at the rendezvous of a future victory there’s a place for all of us.

.

Did you enjoy this article?

We're in the middle of our annual fund drive, and this year we're building our own internal infrastructure for subscriptions, meaning more of every dollar pledged goes to fulfilling our mission. Subscribe today to support our work and be a part of Convergence's next evolution.