The significance of the landslide victory by the United Auto Workers (UAW) at the Volkswagen plant in Chattanooga, TN cannot be overstated. One of the greatest sources of hope for the labor movement in 2024 and beyond is the real potential for an unprecedented wave of union organizing across the US South. For the past 150 years, since the defeat of Reconstruction and its experiment in worker power and democracy, the large-scale unionization of Southern workers has been a puzzle that the labor movement has mostly failed to solve. Creative organizing efforts by multiple unions and workers’ organizations now have learned from the past and are trying new ways to solve the puzzle.

There are plenty of structural reasons for the failures of organized labor in the South: The economy of the region, rooted in the processes of colonialism and racialized plantation slavery, has historically been based on commercial agriculture and resource extraction rather than manufacturing (although this is now changing), and in general has suffered from underdevelopment in relation to the North. On top of this, the political and legal structures of the South have been designed to prevent workers from expressing even the most basic forms of power. Going back to the 1930s, the largely Black Southern workforce in the major sectors of agriculture and domestic service was excluded from National Labor Relations Act organizing rights and Fair Labor Standards Act wage-and-hour protections. Every Southern state has right-to-work laws in place; public sector workers are often prohibited from collective bargaining; and state preemption laws prevent progressive local governments from raising the minimum wage, advancing union rights, or otherwise improving working conditions at private employers. Put simply, organizing unions in the South is really hard.

Today, despite these barriers, Southern workers are on the march. Nearly three-fourths of the 3,213 workers who voted at the Chattanooga plant opted to join the UAW. Their resounding endorsement builds on the momentum generated by the UAW strike last fall and the record contract gains it produced. Thousands of auto workers across multiple states are joining a bold and innovative effort to organize the growing Southern auto sector. Over 3,000 grad student workers at Duke and Emory universities recently voted in two separate landslide elections to join SEIU-Workers United. In the public sector, unions like UE Local 150, the Durham Association of Educators, and United Campus Workers are building power despite decades-old laws outlawing collective bargaining for public workers. These are just a few among countless examples. What they all share in common is a willingness to take risks, and a relentless belief in the ability of Southern workers to build power against the odds.

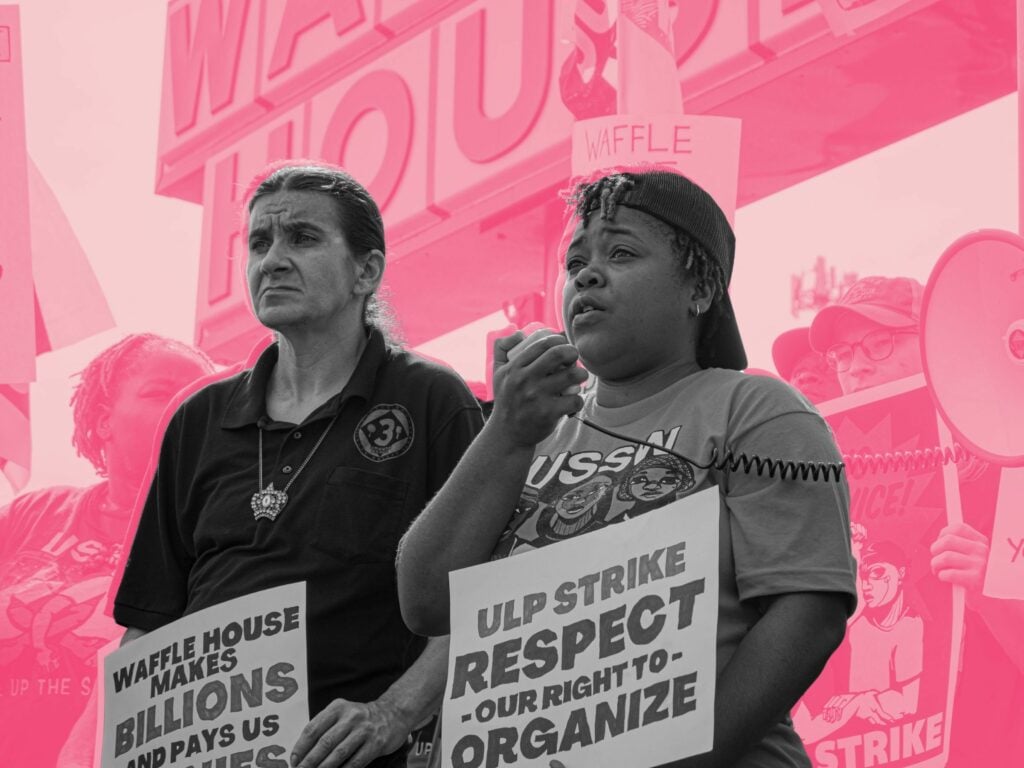

Within this context of growing upsurge, the Union of Southern Service Workers (USSW) was founded in November 2022. It organizes workers across the low-wage service sector in North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia and Alabama, and is concentrated among workers in fast food restaurants, dollar stores, and care jobs. USSW has three goals animating all of its work: 1) win immediate improvements on the job through organizing workplace campaigns; 2) reform the system of Southern labor relations so that all workers, including the most excluded, can achieve dignity; 3) transform Southern society to serve the interests of the working class rather than big corporations.

USSW members are united in a collective struggle against the indignity and exploitation that is common to all low-wage service jobs in the South. Given the high-turnover, transient nature of low-wage service work, and the prohibitively difficult prospect of building power through traditional collective bargaining in those workplaces, USSW focuses on militant direct action and solidarity to build power both within individual worksites and across the service sector. USSW members have formed organizing committees at prominent Southern employers such as Waffle House, and organized cross-employer issue campaigns across geographies around unsafe heat levels and other widely-felt concerns. USSW members have also joined community struggles on a host of issues that impact Southern workers. A foundational principle of the union is the understanding that Southern service workers cannot win on their own. Large-scale improvements on the job can only come about through a broad social movement to win real democracy in the South.

Across the landscape of the Left, there is a growing shared awareness that building worker power in the states of the former Confederacy is necessary in order to fundamentally change the nation. The gaze of the labor movement is once again shifting South. The possibility represented by all of this has created a palpable sense of excitement among workers and trade unionists, and anxiety among corporations and their politicians. Finally, perhaps, we can envision a future where Southern workers have their place in the sun.

The CIO’s Southern organizing drive

In order to formulate strategy for the future, trade unionists and social movement leaders must look to the successes and failures of the past. In 1946, the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) launched Operation Dixie, the largest attempt at organizing the South in the 20th century. CIO President Philip Murray declared that it was “the most important drive of its kind ever undertaken by any labor organization in the history of this country.” At its height, Operation Dixie included over 200 full-time field organizers hired directly to the CIO’s Southern Organizing Committee, with additional organizers assigned from individual unions. Organizing campaigns were launched at a multitude of workplaces in core Southern industries of the time including textiles, woodworking, tobacco and manufacturing.

Pathbreaking unions were formed during that period, including FTA Local 22, at the Reynolds Tobacco plant in Winston-Salem, NC, and FE Local 236, at the International Harvester Plant in Louisville, KY. These radical, anti-racist unions dramatically raised standards for their members and built a multi-racial working class power base in their communities. They offer a model for how workers can win in the South.

Taken as a whole, however, Operation Dixie was a near-total failure. Why didn’t it work? The conjuncture of the late 1940s, characterized by a campaign of anti-communist hysteria and the passage of federal anti-union legislation in the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act, is one factor to consider, but external causes alone are not to blame. A narrowness of vision and multiple strategic errors on the part of the CIO doomed the project from the start:

- Blindspots on race. Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, countless trade unionists at all levels of the CIO stood at the cutting edge of the fight against Jim Crow and white supremacy in the South. Operation Dixie director Van Bittner and his appointed leadership team were not among them. Rather than placing the fight against Jim Crow at the center of the campaign, Bittner’s strategic orientation was to sidestep the messy issue of race, saying that “there is no question of race or national origin in our campaign of organization.” Operation Dixie leaders even went so far as to court the support of viciously racist politicians, such as Strom Thurmond and Bull Connor. In doing so the CIO cut itself off from its most likely base of supporters—Black workers—and crippled its own ability to challenge the roots of the anti-union Southern power structure.

- Divorcing union struggles from social and community struggles. Many of the strongest worker organizing campaigns in the South have gained sustenance from a wide-ranging vision of social change, and solidarity with other groups fighting oppression. Operation Dixie actively disassociated itself from groups organizing around other issue areas, including Black faith leaders and even the CIO’s own political action committee, which was challenging Dixiecrat politicians and pushing for Black voting rights.

- Exclusion of radicals. Socialists and communists were integral to the growth of the CIO, and members of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) played a leading role in many of the most dynamic unions of the time, including in the South. By the time of Operation Dixie’s launch, anti-communist witch hunts were spreading across the country, and left-led groups such as the Southern Negro Youth Congress were under siege. Operation Dixie addressed this dilemma by excluding the participation of any person or organization deemed too radical, in the mistaken belief that by doing so they could avoid similar attacks. Even long-standing Southern allies of the CIO, such as the Highlander Folk School and the Southern Conference for Human Welfare, were pushed to the side because of their radical associations.

- Miscalculations on industrial and geographic concentration. Operation Dixie chose the largely rural and white textile industry as its primary focus, in part because it was the largest single industry in the South. Southern textile was also one of the most notoriously difficult industries to organize, and the CIO had made few inroads despite decades of intense conflict between workers and employers. In contrast, the CIO successfully organized in many other Southern industries before and during Operation Dixie, including steel, lumber, tobacco, rubber, and mining. Even agricultural workers, facing some of the most adverse conditions in the country and lacking NLRA rights, built formidable unions with the Alabama Sharecroppers Union and the Southern Tenant Farmers Union. Many industrial cities such as Winston-Salem, Louisville, Memphis, and Birmingham were poised to become union strongholds by the 1940s. Operation Dixie chose to focus on textiles to the exclusion of those industries and geographies where the conditions for organizing were more ripe, rendering victory harder to obtain for the entire Southern working class.

- Arrogance towards Southern workers. “The Southern Textile Worker is a small-town, suspicious individual, who is extremely provincial, petty, gossip-mongering, who is completely isolated and knows only his mill,” wrote the New York textile workers union official Solomon Barkin in 1939. Southerners were “easy prey” and “mute and undisciplined,” he continued. These types of attitudes towards Southern workers typified many of the high officials of the CIO.

- Short-term investment. Upon its launch in 1946 the CIO billed Operation Dixie as a long-term commitment to organizing the South, but within less than a year, facing setbacks and losses, it pulled the bulk of its resources from the field. By 1948 Operation Dixie had all but disappeared in most Southern states, officially coming to an end in 1953.

What is required of us in this moment?

All kinds of strategic implications flow from the peculiar circumstances of the South, and from the history of efforts such as Operation Dixie. The Southern fortress of corporate power, union busting and low wages—all cemented in place by systemic racism—can seem nearly impenetrable. A multi-dimensional effort is required, deploying varying forms of power and sometimes using unconventional methods. The fight to organize the South isn’t just a question of locating chokepoints of structural power, or unionizing a handful of major companies, or leveraging political instruments, although these are all vital pieces of the puzzle.

Only masses of workers in motion can bring comprehensive change to Southern labor relations. Organizing the South will require a movement-building approach aimed at uniting workers across lines of race, industry, and occupational status, and building links of solidarity across Southern society. It will require diverse forms of organization that can withstand attacks from hostile employers and government institutions. It will require sharp moments of disruption and conflict at strategic focal points. It will require a protracted battle of ideas, culture, and emotions for the hearts, minds and soul of the South.

The South is fertile ground for creative, bold union organizing. Southern workers are a constituency in waiting. The majority of Black Americans, who are the most pro-union demographic in the country, live in the South. There are 2,738,910 production workers, 4,574,830 healthcare workers, and 4,208,010 food service workers in the South, nearly all of them not yet unionized. As of 2023, one in five Southern workers were still making less than $15/hour. Black and brown workers disproportionately occupy the most exploited jobs, but millions of white workers are counted among them, too. What kind of social force can be constructed out of this multi-racial working class, who all share a common interest in a better South?

The South has a rich lineage of worker organizing to draw on, rooted in the Black freedom struggle and expanding outward. Beginning with slave revolts, the underground railroad, and the “general strike” of slaves during the civil war, Southern workers have devised all kinds of creative methods to advance their interests under very oppressive conditions. At key moments, these efforts of Southern workers have shaken the country and forced tectonic shifts of power. During Reconstruction, thousands of Black freedpeople and smaller groups of poor whites in the South banded together to form militant “Union Leagues” of agricultural workers, winning major concessions from landowners with the backing of the Freedmen’s Bureau.

The disruptive 1934 textile strike, centered in the Southern piedmont, pushed Congress towards passage of sweeping labor law reform; the 1969 Charleston Hospital strike helped to spark a wave of hospital worker organizing across the country. When Southern workers have been presented with the opportunity to join unions and other forms of working-class organizations, they’ve done so with enthusiasm. The South is not a barren wasteland of organizing and Southern workers are just as interested in organizing as any other group of workers are. The moment is ripe with the potential for Southern worker power, if we can dream big enough to seize it.

Resources: The information on the history of Operation Dixie was drawn from Michael Goldfield, The Southern Key: Class, Race and Radicalism in the 1930s and 1940s, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020); Barbara Griffin, The Crisis of American Labor: Operation Dixie and the Defeat of the CIO, (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1988); and Patricia Sullivan, Days of Hope: Race and Democracy in the New Deal Era, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992).

Featured image: Organizing at Waffle House, courtesy of USSW.

Did you enjoy this article?

We're in the middle of our annual fund drive, and this year we're building our own internal infrastructure for subscriptions, meaning more of every dollar pledged goes to fulfilling our mission. Subscribe today to support our work and be a part of Convergence's next evolution.