Churchill Downs in Louisville, KY draws people of means from near and far for the running of the Kentucky Derby. It rises like a castle among the one-story shotgun houses of South Louisville. Most of the homes are old, in need of a repair or three. “People say the area is ‘sketchy’ or ‘dangerous,’ said Al Sack, who used to live there, and volunteers with the Louisville chapter of Showing Up for Racial Justice (SURJ). Violence is real, linked in large part to the ravages of drugs.

Violence is also part of the storyline that the mostly white working-class residents of the South End neighborhoods hear all the time. It fuels the “tough on crime” line, the racist dog-whistle that the Right has been using to recruit them for decades. But knocking on doors in that area, Sack and other SURJ volunteers found huge support for ending cash bail. “About 75% fully agreed with us,” Sack said. Even among registered Republicans, about half agreed.

Louisville SURJ has been working to end cash bail for more than four years in a campaign co-created with the Louisville office of The Bail Project. As part of that effort, LSURJ endorsed 13 candidates for local judgeships in November 2022. Seven won. The victory, hopeful in itself, points to ways that electoral work can feed long-term organizing.

“Our goals are to grow a base of support, predominately in majority white poor and working-class neighborhoods where people are impacted by the inequity of wealth-based release from jail and have the deepest shared interest in the change we need,” said Carla Wallace, a SURJ co-founder and member of Louisville SURJ. “This also becomes the base for fights on other issues at the intersection of race and class,” she said.

Cash bail: poor people rot, rich people walk

“You feel like you’d do anything to get your child out. I thought of selling everything I owned, but that wouldn’t be enough,” said Patricia Adams, a volunteer with Louisville SURJ. Her son Lucius landed in the Louisville Metro Detention Center (LMDC) after his December 2019 arrest and stayed for more than three years. A single mom, Adams couldn’t pay Lucius’ bail, even with her three jobs, even when it was knocked back from $100,000 to $25,000. The average felony bail of $10,000 amounts to eight months’ income for a typical defendant. “That’s the issue at hand here. There’s justice or lack thereof for the poor, and a more expedient route for the rich,” Adams said.

Cash bail is supposed to guarantee that a person accused of a crime returns to court. Some guidelines exist, but judges have wide leeway in setting bail. Defendants facing the same charges may get high, low, or no bail. If, like Lucius, they can’t make bail, they remain in local jails awaiting trial. Of more than a half-million people in local jails in the US, more than 80% have not been convicted of a crime. By law and the Constitution, they’re presumed innocent.

“We don’t really believe that, because if we did, this wouldn’t be an issue. We assume people are innocent but yet we’re holding a whole lot of them in jail before they have pled or been found guilty of anything,” said Kungu Njuguna, policy strategist for the ACLU of Kentucky.

The price paid by defendants and their families far exceeds the money burden. Even a few days in jail can cost a defendant their job; longer holds put their housing and even custody of their children at risk. The trauma affects those on both sides of the jail door, as Shameka Parrish-Wright knows.

For families, “it’s like you’re doing the time with them. You’re waiting, you’re scared, you don’t know what’s happening, you have to come up with legal fees, phone call fees, take them things they need if you’re allowed to, and you worry about your loved one being inside,” said Parrish-Wright, the former director of The Bail Project’s Louisville office, now executive director of VOCAL-KY. She had been arrested at 18 for defending herself against an abusive boyfriend.

“The police came for me and I told them what happened and they put those cold, hard cuffs on me, and I did not understand. If you don’t have money, if your family doesn’t know you’re in there, it’s the scariest thing. Jail is hell no matter what level. It’s demeaning. When you’re poor, you have to prove yourself innocent,” she said.

Under the physical and psychological pressures of incarceration, many defendants also end up pleading guilty just to get out, as did Parrish-Wright, and Patricia Adams’ son Lucius. After three years in a dorm built for 20 people that held 45, with no exercise, no fresh air, no sunlight, Lucius went to court. His lawyer thought he had a good chance of beating his charges—but on day two of the trial, he took a plea instead.

“He said, I can’t do this anymore, Mom, I can’t do this anymore. I’m just, I’m going to take the plea’,” Patricia Adams said.

And cash bail isn’t even needed. Experiences from around the country, including those of The Bail Project in Louisville, show that defendants make their court dates without it.

End Cash Bail campaign

The Bail Project runs a national revolving bail fund. Its two dozen local projects pay bail for people in need and provide community support to ensure that they get to court. “Our return rate—people returning to court and completing their cases—was 90%, better than the 70% for people released on their own recognizance, not just in Jefferson County but across the state,” Parrish-Wright said. The Bail Project sees its work as “combatting mass incarceration by disrupting the money bail system—one person at a time.” Their experience helps make the case for long-term policy change, and they commit to working in local coalitions to make that happen. In Louisville, the SURJ chapter became their closest partner.

SURJ runs a Court Watch program and ongoing canvasses to build support for ending cash bail. Both of those projects informed the 2022 judicial elections—and the election work in turn strengthens the ongoing outreach.

In the Court Watch, started at The Bail Project’s suggestion. SURJ volunteers observe arraignments two or three days a week. They take notes on when and how judges use their huge discretion to set bail, observing how race, the presence of a private attorney, and other factors influence the decision. Periodically they also meet with judges to review the patterns they see.

“The Court Watch program has a transformative effect on volunteers, and we have heard that it has a big impact on judges as well,” Carla Wallace said. “Providing a level of transparency and accountability for their decisions is core.”

Talking bail

While people of color are over-represented among those in jail awaiting trial, there are many ways to talk with people about cash bail, Parrish-Wright said. “I start showing the relevance and how we’re interconnected.…The damage that substance use and the opioid crisis has done to our cities and our state, from the hood to the holler, means that more people have a connection to incarceration than they realize,” she said.

SURJ began door-knocking for the End Cash Bail campaign in 2018. Volunteers canvassed the predominantly white working-class neighborhoods of South Louisville. When they got a warm reception, they asked people to sign postcards opposing cash bail, which would go to local judges.

Often their experiences on the doors mirrored Parrish-Wright’s.

“Almost everyone I talked to knew someone who had been involved in the system—although some had family members who were correctional officers or police officers and they were hesitant to engage,” Al Sack said. “Poor white people who’ve had a family member involved know judges have bias against poor white people, are more likely to see them as dangerous. Even if they had never been to jail, people can realize that it could be them someday.”

Unlike most criminal justice issues that polarize left to right, “this polarized from top to bottom,” said Alex Flood, SURJ lead organizer for Kentucky. “When we said this is a wealth-based issue, and not a criminal justice issue, that really resonated with people.”

Election opens opportunities

Residents of Louisville/Jefferson County (the city and county merged in 2000) elect district, circuit and appeals court judges. All the seats across the county courts came open in 2022. Local judges, mostly those in the district court, set charges and bail. Electing judges who were committed to bail reform and to equity in the court system could both improve outcomes for individual defendants and build more traction for ending cash bail.

SURJ based its endorsements on its Court Watch records, a candidate questionnaire, and interviews conducted under the strict state laws governing contact with candidates for judge. Up until eight days before the election, volunteers incorporated information on the judges into their ongoing canvassing. Supportive voters got a copy of an endorsement card that explained, “Judges are the elected officials we’re most likely to interact with directly. They also have a big impact on our communities.”

Just before the election, SURJ switched into GOTV mode, branching out into new neighborhoods, starting a text campaign, and hand-delivering 2,600 endorsement cards to people who had signed “End Cash Bail” postcards. On the day early voting started, they also held a press conference with allies and community leaders.

Almost all the work was done by volunteers. SURJ built a “distributed organizing” model: Members invited supportive people they met on the doors or at actions to join them as volunteers; staff helped volunteers and members build the skills needed to lead parts of the work. Altogether about 100 people worked on the judicial campaign, 40 on the doors and 60 in other roles.

“Elections and electoral work are a great way to find people who are values-aligned with you as an organization because their values align with the candidate that you’re working for,” Flood said. The work can also force organizations to scale up. Over the four years of the End Cash Bail campaign, SURJ had door-knocked somewhere between 9,000 – 11,000 homes. In Spring 2022, they hit more than 11,000 doors in four months to support State Rep. Attica Scott’s primary bid for US Congress. Volunteers from that campaign, like Al Sack, got involved in the ongoing End Cash Bail work.

Electing allies

Louisville voters supported a majority of the SURJ-endorsed candidates. In the highest-profile contest, Black progressive lawyer Tracy Davis edged out incumbent Judge Mary Shaw, who signed the no-knock warrant that led to Breonna Taylor’s death.

SURJ had canvassed 24 of Jefferson County’s 674 precincts over the four years of the End Cash Bail campaign. In those precincts, Davis beat Shaw by 870 votes—more than one-third her margin of victory. To try to get a hard-data assessment of the effectiveness of their work, SURJ compared a precinct where they had canvassed and distributed literature and yard signs to two others with similar demographics where they hadn’t worked. Davis won the canvassed precinct by 23.4%, won one of the others by 9.4% and narrowly lost the third.

The week after the election, SURJ invited the winning judges to a Zoom call—part of the process of building relationships and accountability. The ongoing Court Watch will contribute to that as well. Volunteers will continue to canvass—and the End Cash Bail campaign is connecting with the growing opposition to building a new jail.

No new jail!

“Bail has crept alongside this train that led to mass incarceration,” Shameka Parrish-Wright said. Pretrial detention increased 433% between 1970 and 2015. The Louisville jail, regularly filled past capacity, bears witness to this explosion. In these circumstances, pretrial detention can be deadly.

Patricia Adams knew this. COVID hit just after Lucius was incarcerated. She felt like she had to do something. “I made a big sign on posterboard that said, ‘Innocent until getting COVID?’ and went downtown by myself,” she said. “It was on Freedom Friday, where everybody drove around the courthouse saying, ‘release the prisoners so they don’t die of COVID.’ You know, they don’t deserve a death sentence.” That’s where she met Louisville SURJ, which organized the event.

Just in the last 14 months, 13 people have died in the jail. “Several of the last five have been homeless folks who just don’t have a support system,” Adams said.

In response to the deaths, the ACLU of Kentucky convened Community Stakeholders to End Deaths at LMDC. “It’s a great group of community orgs who don’t necessarily agree on everything, but we agree the deaths aren’t right,” Kungu Njuguna said. Each group in the coalition has its lane. The ACLU works with the County Attorney’s office. It also focuses on working with Metro Council, the local legislative body, as do many other groups. Several groups concentrate on educating the public. SURJ participates, adding its work with the judges to the mix.

LMDC’s latest victim, Ishmael Worth Puckett, passed on Jan. 9, 2023. “Politicians will use his death as argument to build a half-billion-dollar jail,” Carla Wallace said, “but we’re focused on lowering the numbers of people in jail.” Ending cash bail could make the new construction unnecessary.

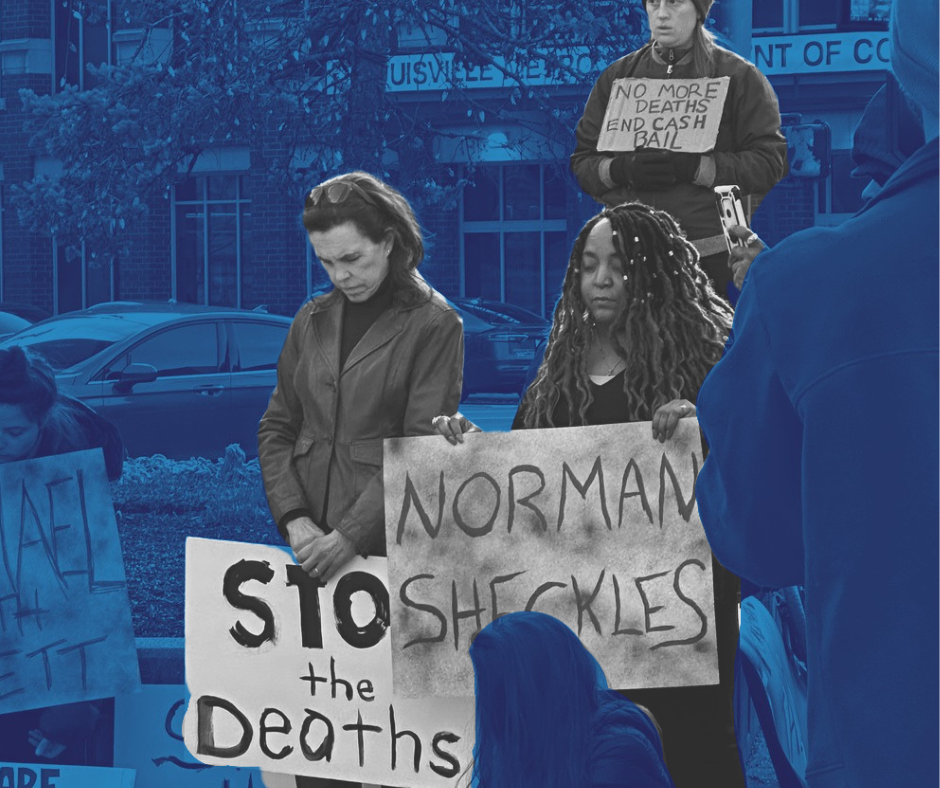

SURJ and other members of the stakeholders’ group, including the ACLU, VOCAL-KY and the Buddhist Justice Collective, came together for a silent vigil in front of the jail after Puckett’s death. They took note of the immediate tragedy and the big picture.

“We continue to hone what it means to strategically work together,” Carla Wallace said. “Electing judges committed to reform is an important step on the road to transformative change, with deep implications for what kind of community we want to be—but none of the pieces can work alone.”

Featured image: Vigil at the Louisville jail on Jan. 10, 2023 after the thirteenth death in the jail in just over a year. More than 80% of the people in jail nationwide have not been convicted of crimes; they’re incarcerated because they can’t make bail. On the left in the photo, Carla Wallace of Louisville SURJ; on the right, Shameka Parrish-Wright of VOCAL-KY. Photo courtesy of Louisville SURJ.

Did you enjoy this article?

We're in the middle of our annual fund drive, and this year we're building our own internal infrastructure for subscriptions, meaning more of every dollar pledged goes to fulfilling our mission. Subscribe today to support our work and be a part of Convergence's next evolution.