Today is October 13. Ruth Bader Ginsburg died twenty-five days ago.

Eight days later, her proposed replacement was named. The Rose Garden ceremony celebrating the announcement became a COVID-19 super-spreader event. Donald Trump got sick, took a helicopter to the hospital, and was soon back in the White House, calling up Rush Limbaugh and Fox News and blaming Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer for the right-wing paramilitary plot to kidnap her. He says he wants a deal on COVID relief, says he doesn’t, then says he does.

McConnell’s laser focus: Stack the judiciary

Either way, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell isn’t moving on any real relief and by all signs has never had any intention of doing so. McConnell is focused on pushing through Ginsburg’s replacement in the final days before the election, notwithstanding past arguments against “robbing” the people of the chance to weigh in on such a decision. Packing the federal judiciary – and not only the Supreme Court – has been McConnell’s singular goal as majority leader from day one.

Speaking to the Federalist Society last November, he explained his objective: “do everything we can for as long as we can to transform the federal judiciary, because everything else we do is transitory.” As of September 25, 218 Trump nominees had been confirmed, making up one quarter of active federal judges requiring Senate confirmation. As of Monday, the hearings on Trump’s Supreme Court nominee are underway.

So, in typical time-warping 2020 fashion, a lot has happened since September 18, and it can be hard to keep up with all the assaults, crises, and provocations.

Crazy way to run a country

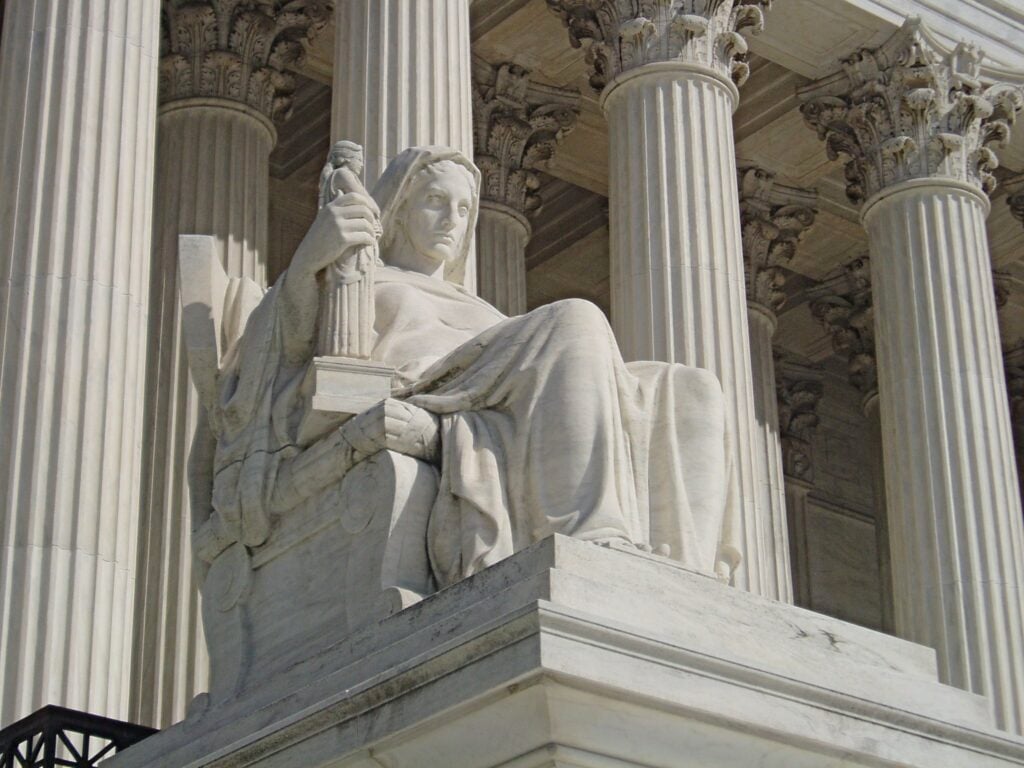

The Supreme Court for years has been an utterly detectable political iceberg. With Ginsburg death, we’ve barreled straight into it. Given the power the Supreme Court exercises now, just about everything progressives and people on the left hope for or fear hinges on its composition, starting with how the outcome of the election may well be determined.

That’s nuts, of course. “Nothing important should turn on whether some old person chooses to retire or keep working until they’re in their 90s,” law professor Daniel Epps recently told Politico. “It’s a crazy way to run a country.”

All sorts of questions hang in the balance. Will the Court keep rubber-stamping disenfranchisement and locking in white minority rule? Will it block us from establishing much-needed public goods? Will it tie the hands of federal agencies to act on climate change or to hem in corporate power? Will it overrule decisions on reproductive freedom or trans and queer rights? And so on.

Since at least the Kavanaugh hearings, progressives concerned about the federal judiciary have been waving their arms, trying to get Democrats to pay more attention. Though federal court reform hasn’t historically been at the top of the agenda for social movement organizations, this summer progressive groups successfully pushed the Democratic Party to include a mention of “structural court reforms” in its platform.

In the last three weeks, the conversation over the courts has picked up lots of speed. Proposals to expand the federal judiciary (and make it more representative of the country), reform it through term limits, and/or reduce its power through jurisdiction-stripping and other measures have moved from the pages of law reviews and policy-oriented left media to the mainstream press. The Court has become a campaign issue, too, with Joe Biden facing questions about where he stands on expansion. And, with the confirmation hearings this week, the Supreme Court has again landed at the top of the news.

Push the conversation further

We can’t afford to let this discussion wane. The shift in conversation over the past three weeks signals an important opening to challenge the federal courts as an anti-democratic force. And, for progressive and left organizations particularly, the conversation is a reminder that, as things stand now, there’s no effective agenda for governing power if it doesn’t address what to do with the federal courts.

Beyond the immediate issue of a contested election, this fact raises numerous questions from the perspective of left strategy. How should we think about federal courts and what expectations should we have of them? Where should federal court reform fit into our agenda? How would we build a constituency or coalition broad and powerful enough to win that reform?

If Democrats win in November and we’re able to move federal legislation, how do we prepare to defend that legislation when the fights inevitably move into the federal courts? And how do we grapple with the legitimating power of federal courts? In other words, how do we drive meaning-making of our own around questions of law, democracy, and justice?

Shatter the myth that courts are not political

In her opening statement to the Senate Judiciary Committee, Trump’s Supreme Court nominee referred to the “political branches” of the state, meaning Congress and the Presidency. Part of the longstanding mythology of the federal courts – and an element in what’s been called liberal Court veneration – is the idea that the courts stand outside politics.

We know that they never have. The 2013 evisceration of the Voting Rights Act’s key enforcement mechanism is among the most outrageous of examples of the past decade. But there are a host of recent politically consequential decisions – decisions often based on class, racial and gender injustice – on issues beyond voting rights and election procedures. And, historically, from taking action to secure white sovereignty or consecrate corporate power, the Supreme Court has time and again enacted reactionary politics under the guise of legal neutrality or loyalty to the Constitution.

A reckoning with the courts can’t happen without good organizing. The past few years have seen a surge in electoral organizing among social movement groups and, along with it, a drive to take on fundamental questions about elections, systemic racism, and democracy. This has inspired broadly popular efforts to expand voting rights, like the smart, tireless campaigning that won more than 64 percent support for Florida’s Amendment 4. It has also prompted House passage of the For the People Act and the Voting Rights Advancement Act, as well as discussions about what it would take to curb minority rule, from expanding the number of states to eliminating the electoral college. That’s the kind of change we need if we want democracy.

Those who have been shining a spotlight on the federal courts are calling for a similar kind of thinking, and a similar dedication to the fight. As we formulate a specific action agenda, there will be debates about what is achievable at what stage, whether to expand seats or set term limits or both, and other democratizing proposals. But, no matter what shape the fight takes, the antidote to conservative capture isn’t a “return to normal.” It’s winning a federal court system worthy of our democratic aspirations.

Did you enjoy this article?

We're in the middle of our annual fund drive, and this year we're building our own internal infrastructure for subscriptions, meaning more of every dollar pledged goes to fulfilling our mission. Subscribe today to support our work and be a part of Convergence's next evolution.