Gloom shrouds the news on the economy. Workers get blamed for inflation and the common solutions on offer bring more pain. But when we center the interests of workers and communities, we get a different picture of the causes and cures for our economic woes. While wage increases can contribute to inflation, they don’t have to. Corporations can absorb higher wages by cutting profits or CEO salaries, for example. In fact, the increases in workers’ wages have barely brought them up to pre-COVID levels, while CEO pay and profits have increased exponentially. And there are other key sources of inflation such as energy prices and supply chain issues, that are more significant than wage increases.

The Federal Reserve, usually presented as a gray eminence above the fray, actually plays out a distinct neoliberal agenda—one that sees higher unemployment as an aid in disciplining the workforce. Raising interest rates is far from the only answer to inflation. Investments in clean energy could help bring down fossil fuel prices, for example; targeted policy interventions could help un-kink the supply chain. And powerful people-centered movements could rein in corporate power.

Our new series, “People-Side Economics,” expands on these perspectives, exposing the bias and half-truths we hear every day, and bringing ideas we can use in organizing. In this third installment of the series, Economic Policy Institute President Heidi Shierholz talks with Convergence editorial board member Stephanie Luce about what does—and doesn’t—cause inflation, and how worker power plays a part in fighting it.

Stephanie Luce: A lot of people are feeling quite anxious about inflation these days. What can you tell them about what’s going on?

Heidi Shierholz: Commentators say all the time that high wages are driving inflation, but it isn’t true. Wages do have some impact, but they are dwarfed by other things.

Policymakers and public commentators who don’t want things like a high minimum wages are using inflation as an excuse to say we can’t do them, but they are wrong. Things that raise wages for working people are more important than ever right now to offset the hardship that comes with high inflation. Now is absolutely the time we need to raise the minimum wage—it is not going to contribute in any meaningful amount to inflation. And it’s crucial, because inflation is a hardship, particularly for our lowest wage workers.

SL: Are there other solutions that would be the right thing to push for now?

HS: The other thing is union contracts. People are arguing that we can’t have strong union contracts because of inflation fears. That is absolutely not the case. This is the time when people need to be getting higher wage increases. Inflation over the last year was 8.5% so if people aren’t getting at least an 8.5% increase, they are actually seeing a cut in their living standards. This makes it all the more important to raise wages.

We hear it in other things about strengthening labor standards, such as the efforts at the federal level to raise the overtime threshold. Trump weakened this, and it should be raised. However, we see resistance from policymakers who point to inflation as a concern. But our temporary spike in inflation, which will be virtually unaffected by where the overtime threshold is set, should not be informing that policy decision.

SL: What are the factors that are really driving inflation?

HS: It’s pandemic and war-driven. The war in Ukraine impacted fuel prices, but we’re already seeing gas prices come down. So that’s good news.

Then there are the other pandemic-related factors that fortunately are now abating. We had massive supply chain problems that were due to COVID, because of rolling port shutdowns and related factors. Also because people made a shift in purchases from services to goods, such as dropping a gym membership and buying at-home gym equipment, or canceling travel but buying furniture. That created snarls in the supply chain that boosted prices.

Corporate profits are also a key driver of our spike in inflation. I don’t think that corporate greed actually increased over this period, but corporations are always trying their hardest to make more profit and they have capitalized on the pandemic and war-related factors to increase their profits. The data shows this to be true.

You can break down the price of most goods and services into three main components of costs: (1) labor costs, like wages and benefits; (2) non-labor inputs, like equipment, materials; and (3) corporate profits. And, in this recovery, corporate profits explain 40% of the rise in prices, about three times more than normal. So consumers are paying higher prices and corporations are raking it in.

SL: What are the implications of all of this for the average person who is worried about the economy?

HS: We need to think about power, and I’ll focus on worker power. In general, workers have two potential sources of power. One is the implicit threat that they could quit and take a job elsewhere. The second is joining together with their coworkers to make demands, as in a union. That’s it. That’s what that’s what workers have.

It was unexpected, but the extraordinary circumstances of the pandemic recovery––basically our truly groundbreaking COVID relief and recovery measures––have led to strong job growth. The strong jobs recovery has made it much more possible for workers to quit to take better jobs. Now, the possibility that workers could find a better job elsewhere is much more real for employers, which has shifted power to workers.

And then on the organizing side, union favorability is now at its highest in almost six decades:71% from the most recent Gallup poll.

There are lots of reasons for this. One is the fact that workers are seeing high-profile organizing drives, like at Amazon and Starbucks. And that kind of attention helps workers recognize that coming together with their co-workers is an option for them if they are being treated unfairly.

So there has been action on both these fronts: workers’ power to quit, and workers organizing.

But, with the Fed taking aggressive action to slow the economy, we are likely to see changes. Job growth is already starting to slow, and it’s likely to slow further. If unemployment rises, that will dry up the increase in worker power that workers have had from the increased ability to quit their job to take a better job.

But I want to be clear that an increase in the unemployment rate doesn’t have to dry up the other source of worker power, the power in organizing.

I think there has been a kind of structural shift in workers recognizing their power and the importance of collective action. That is a lesson learned, and that’s not going to immediately go away when the unemployment rate rises. A rising unemployment rate will put some pressure on it, because having high jobs availability makes it much less risky for workers to organize. While organizing is technically legally protected, it is largely not protected in reality, because of weak enforcement, lack of penalties, etc. So a higher unemployment rate puts pressure on that organizing momentum, but I do not think we’re going to see a wholesale drying up. I think that momentum will last, but we all have to work hard to support it.

SL: It seems like there’s an important lesson for organizers: let’s inoculate people, to prepare for the fact that unemployment may rise. And let’s build our collective support for the unemployed workers in solidarity with worker organizing.

HS: Yes. I think this talk of “are we in a recession right now?” is sort of confusing because we’re pretty obviously not in a recession now. But we should be clear that things will likely change.

And when they do, organizing unemployed workers is key.

If we fall into a recession in the coming months, many will blame it on the COVID relief and recovery measures––they say those measures caused inflation. That is incorrect, and that kind of narrative will make it harder to do the kind of relief and recovery that we will need again.

So we might have people in much more dire situations than they were when unemployment benefits were much stronger during the thick of the COVID recession. That means there’s going to have to be a lot more organizing to have a real movement to support unemployed workers. But we shouldn’t assume that organizing has to slow down just because there is a rise in unemployment or a recession.

SL: Like in the 1930s.

HS: Right.

SL: Are there solutions we should be pushing to deal with inflation?

HS: The good news is the drivers of our spike in inflation are weakening. Gas prices are coming down. Supply chain issues are abating. Consumers’ spending patterns have normalized. Wage growth is slowing. But because inflation is being driven by global forces, there is little policymakers can do to fight it directly. That means that the most important things to push policymakers to do are things that help people who are most harmed by inflation, like raising the minimum wage, expanding the Child Tax Credit, and more. I think that is the right way to address this until it naturally comes down.

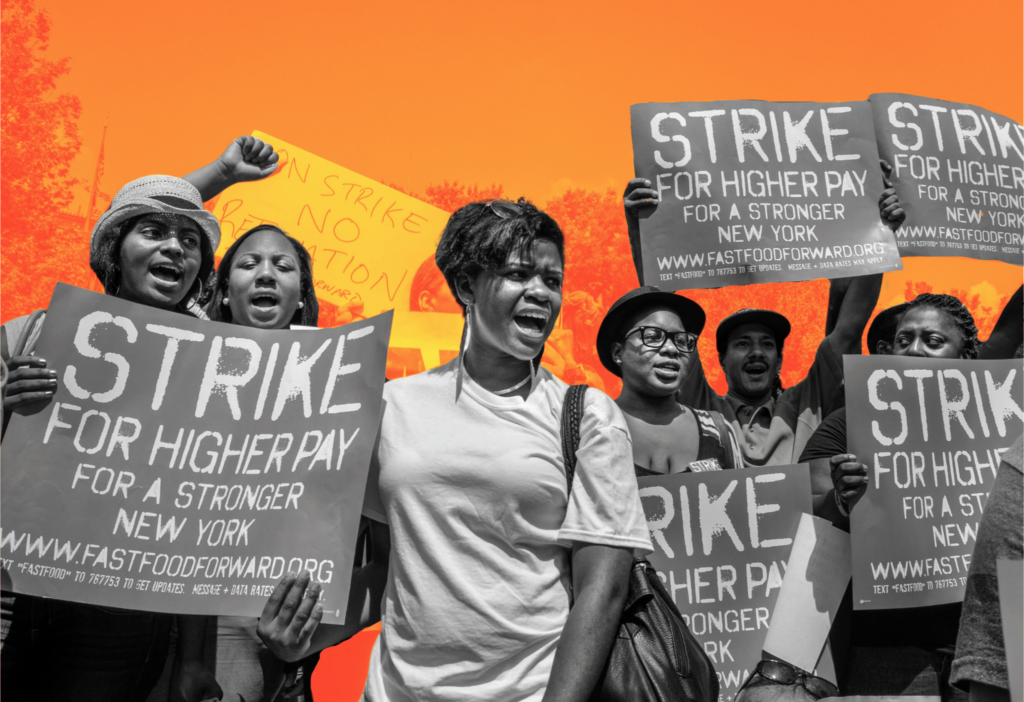

Featured image: Fast food workers on strike in New York City in July of 2013. Photo by Annette Bernhardt, via Flickr (Creative Commons, modified).

Did you enjoy this article?

We're in the middle of our annual fund drive, and this year we're building our own internal infrastructure for subscriptions, meaning more of every dollar pledged goes to fulfilling our mission. Subscribe today to support our work and be a part of Convergence's next evolution.