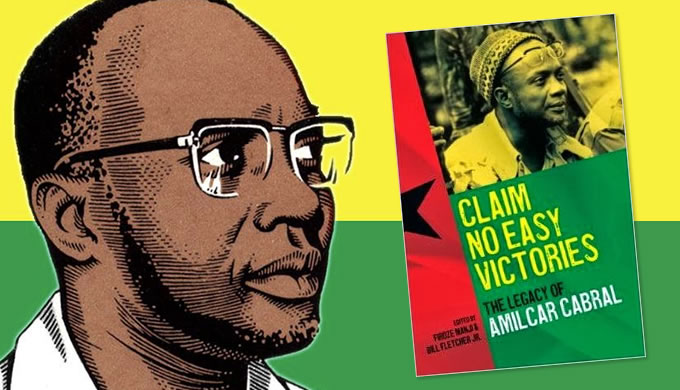

This essay is published in the book “Claim No Easy Victories: The Legacy of Amilcar Cabral,” published by CODESRIA, Senegal, available in the US at Powell’s Independent Bookstore Online.

Join the Bay Area Book Launch event featuring book contributor Walter Turner, host of KPFA’s “Africa Today,” and María Poblet, on 2/21 at 6pm at Oakland’s Eastside Arts Alliance. Full event information »

As a Left community organizer in the United States, working with oppressed and exploited people in the San Francisco Bay Area of California, I have benefitted greatly from Amílcar Cabral’s work and thought. I am part of a broader growing political tendency that is building a working class base for the Left in urban centers inside the United States, innovating with organizing fights for housing and transportation, immigrant’s rights, and women’s rights, building race-conscious class unity, particularly between oppressed communities of color who are pitted against each other at the bottom of the economy in the US, and have a strong basis for solidarity with working class and poor people throughout the world.

Like a lot of radical political organizing in the 21st century, our tendency, in part, comes out of critiques of the 20th century socialist models. From rejecting the authoritarianism of Stalin, to broadening the concept of the revolutionary subject to include a broader set of marginalized groups not limited to the industrial working class, to rejecting race-blind class reductionism, to lifting up the liberatory aspects of cultural traditions among oppressed people.

Amilcar Cabral’s work has been profoundly influential to the development of this political tendency, among many others around the world. His theory provides a way to engage with the shortfalls of 20th century models of radical change that do not throw the class struggle baby out with the Soviet bathwater. Cabral is a luminary among the broader set of Third World Marxists who, from Nicaragua to Kenya, led successful national liberation movements. He formed and led the PAIGC, and was instrumental in strategizing the successful overthrew of Portuguese colonialism, not only in his home of Cape Verde & Guinea Bissau, but also throughout the continent of Africa. He was core to the development of a broader Pan-Africanist tendency, which built strong links to liberation movements in Asia and Latin America, and had inspiring, global impact.

Even in the United States, the belly of the beast, in such a markedly different time, place and set of conditions than the ones Cabral operated in, we have a lot to learn from his work. He grappled with theoretical questions that have parallels to the ones we face today. And, he reached a level of depth and sophistication regarding movement strategy that we have yet to achieve in the 21st century.

Revolutionary Democracy

Today’s emerging movements in the west hold Democracy to be a core value. They have have emphasized collective decision-making as an attempt to increase engagement, inclusion, and community control. This approach, heavily influenced by Anarchism and Zapatísmo, attempts to remedy problems attributed to top-down approaches by Left political parties of the 20th century. The vast majority of the people involved in those movements have little knowledge of Cabral’s insights on the question of what he called “Revolutionary Democracy.”

Cabral’s work presents a different approach, in a very different context, with some of the same values. His advice to militants in his organization reflected a commitment to revolutionary democracy: ‘Do not be afraid of the people and persuade the people to take part in all the decisions which concern them – this is the basic condition of revolutionary democracy, which little by little we must achieve in accordance with the development of our struggle and our life.’ (1) He addresses this question in a dialectical way, acknowledging what our movements have been beginning to understand: that oppression and exploitation rob people of the capacity to self-govern, both structurally and psychologically, and that building that capacity is a core task within the revolutionary struggle, and not after. This very same assessment is built into radical community organizing that seeks to develop working class leaders who can advance the social justice movement as a whole. Structures of support, capacity-building, and decision making that we have built in the community organizing sector prioritize people directly impacted by the problems of capitalism, and are attempts to build that kind of revolutionary democracy within our progressive movements.

Cabral called for both collective and individual leadership, and theorized the role of individual leadership as part of a collective whole. He said ‘The leader must be the faithful interpreter of the will and the aspirations of the revolutionary majority and not the lord of power’. (2) This approach affirms the role of leaders in and developing the vision emerging from the people, while not putting leaders on a pedestal of unchecked power. To that end he called on militants to ‘Tell no lies, claim no easy victories,’ and encouraged a practice of profound humility, honest evaluation, and integrity throughout his organization.

He also theorized collective leadership:

To lead collectively, in a group, is to study questions jointly, to find their best solution, and to take decisions jointly, it is to benefit from experience and intelligence of each and all so as to lead, order and command better. In collective leadership, each person in the leadership must have his own clearly defined duties and is responsible for the carrying out of decisions taken by the group in regard to his duties… But to lead collectively is not and cannot be, as some suppose, to give to all and everyone the right of uncontrolled views and initiatives, to create anarchy (lack of government), disorder, contradiction between leaders, empty arguments, a passion for meetings without results. Still less is it to give vent to incompetence, ignorance, intellectual foolhardiness…In the framework of the collective leadership, we must respect the opinion of more experienced comrades who for their part must help the others with less experience to learn and to improve their work. In the framework of the collective leadership there is always one or other comrade who has a higher standing as party leader and who for this reason has more individual responsibility…We must allow prestige to these comrades, help them to have constantly higher standing, but not allow them to monopolise (take over) the work and responsibility of the group. We must, on the other hand, struggle against the spirit of slackness, and disinterest, the fear of responsibilities, the tendency to agree with everything, to obey blindly without thinking. (3)

The PAIGC was so committed to being an instrument of the people, that, in 1973, after more than a decade of armed struggle, when they finally defeated Portugal militarily, they did not storm the palace of power. Rather, they returned to the people, conducting a vote of confidence among the population, affirming their approval through a popular vote before officially taking up governance. This referendum is a powerful example of revolutionary democracy.

What would today’s movements look like if we had highly effective, collectively controlled instruments of political struggle? What would organizations look like if we held individuals to high standards of integrity, provided structured developmental support, and consciously built our capacities towards governance?

Re-imagining political power is a central challenge to today’s 21st century generation of freedom fighters. I have been part of experiments in structure that sought to uphold the value of collective leadership, from flat collectives to ultra-democratic centralism, to developmental hierarchies that focused on in-depth training and mentorship for emerging leaders. These approaches, none of them perfect, have re-enforced the core lessons that Cabral offers: the need for clarity on the outcomes you seek, the necessity for alignment and accountability, and the value of collective leadership among people who share a political goal.

Class analysis & class consciousness

Cabral argued that no revolution could be truly successful without leadership from the working and peasant classes whose work produced the wealth of the country and of it’s colonizers, and whose strategic position was powerful enough to turn the tables on economic injustice. And that a revolutionary vision of liberation would not be satisfied by simply replacing Portuguese political and economic control, putting the national bourgeoisie at the top of the exploitative structure created by colonialism.

Gaining political representation or even political control would not be sufficient to truly change the economic structure that colonialism put in place. Neither would it be possible or ideal to return to the way indigenous societies were organized before colonialism. So, Cabral argued, the task of revolutionaries was to make possible the development of national productive forces (the capacity of Cape Verde & Guinea Bissau to sustain an economy independent of Portugal), while laying the ideological foundations and movement infrastructure to fight against exploitation that would emerge under the rule of the national bourgeoisie.

This sophisticated strategy came from a deep conviction in the fundamental right of his people to live free of exploitation of any kind. He described the national liberation movement in this way: ‘We are fighting so that…our peoples may never more be exploited by imperialists not only by people with white skin, because we do not confuse exploitation or exploiters with the colour of men’s skins; we do not want any exploitation in our countries, not even by black people.’ (4)

Today’s reality is one where the exploiting class is no longer made up only of European colonial rulers. There are plenty of political and corporate leaders from oppressed nationalities, some of whom use their oppressed identity as an excuse to not only exploit others, but to celebrate that exploitation as if it were a hallmark of progress.

The question of class exploitation was core to Cabral’s strategy, and is just as important for freedom fighters today. Without organizing working class people from oppressed nationalities, our movements lack the strategic base of power that can challenge capitalism’s core. Without organizing working class and peasant communities, our movements can easily remain focused on social issues without tackling the underlying economic structure of capitalism. That is why organizing working class people is so important to building a successful movement towards economic democracy.

He also detailed the role of privileged layers of society in the revolutionary project. The fact that the national petty-bourgeoisie live the contrast between the world of the colonizer and the world of the colonized, he said, could be a catalyst for revolutionary consciousness. In fact, he theorized, these layers of society who were privileged in some ways but still not owners of the means of production were likely to see the need for national liberation sooner, given their role in society and in the economy:

The colonial situation, which does not permit the development of a native pseudo-bourgeoisie and in which the popular masses do not generally reach the necessary level of political consciousness before the advent of the phenomenon of national liberation, offers the petty bourgeoisie the historical opportunity of leading the struggle against foreign domination, since by nature of its objective and subjective position (higher standard of living than that of the masses, more frequent contact with the agents of colonialism, and hence more chances of being humiliated, higher level of education and political awareness, etc.) it is the stratum which most rapidly becomes aware of the need to free itself from foreign domination. This historical responsibility is assumed by the sector of the petty bourgeoisie which, in the colonial context, can be called revolutionary, while other sectors retain the doubts characteristic of these classes or ally themselves to colonialism so as to defend, albeit illusorily, their social situation. (5)

Organizers in the 21st century can learn from this type of detailed assessment based on the time, place and conditions, and should be asking ourselves these same questions. What is the most strategic role for privileged layers of society in social movements today?

The economic crisis has pushed more and more racially privileged and self-identified middle class people into precariousness and even poverty. Foreclosures, unemployment, loss of pensions, and lack of basic resources like healthcare are no longer problems unique to the self-identified working classes. While it is true that these privileged sectors have not felt the brunt of the burden of the failures of neo-liberalism, denying their experiences, or writing them off as irrelevant to the movement is a self-marginalizing mistake. Unless we can leverage this opportunity to provide new entry points into the movement, and engage the falling “middle class” in the project of fighting for economic justice for the working class as a whole, our movement will not be able to grow to the scale we need to win. Nor will we be able to capture the imagination of society as a whole.

How to best engage privileged sectors is a complicated question. Just as capitalism has robbed oppressed and exploited people of leadership capacities, it has ingrained privileged people with a complex of superiority that undercuts our collective capacity for revolutionary democracy. A more nuanced understanding that recognizes that we all have experiences of privilege and oppression allows us to build a more intersectional analysis. Just as Cabral theorized the unique potential of a sector of the petty-bourgeoisie, while positioning the working class as the motive force of change, our movement should also get clear on the role of particular sectors of the falling “middle class,” in a broad multi-racial, multi-cla

Did you enjoy this article?

We're in the middle of our annual fund drive, and this year we're building our own internal infrastructure for subscriptions, meaning more of every dollar pledged goes to fulfilling our mission. Subscribe today to support our work and be a part of Convergence's next evolution.