Strikes against employers and rank-and-file struggles for union democracy and reform often go hand in hand, or at least overlap. While tens of thousands of University of California employees have been engaged in the largest higher education strike ever, they have, as members of the United Auto Workers (UAW), also been strong supporters of a major campaign to revitalize their own national union.

In 2021, many UC workers were part of a successful movement to change the UAW constitution so its top leaders could be chosen through direct elections, not easier-to-control union conventions attended by a few thousand delegates. As a result, all working members of the UAW and retirees received referendum ballots this fall enabling them to choose between candidates backed by an opposition group called Unite All Workers for Democracy (UAWD) and the Administration Caucus, which has controlled UAW headquarters for 75 years.

Confounding all expectations, the UAWD challengers won four top positions and face January run-off elections for the union presidency and two other positions. At a time when younger activists around the country are embracing a “rank-and-file strategy” to increase the effectiveness of their union organizing, bargaining, and strikes, this UAW election victory has been an inspirational backdrop for the UC contract dispute. After a six-week strike, the academic workers “ratified a pathbreaking new contract that brought most of them 50-60% increases within the next two-and-a-half years,” Nelson Lichtenstein wrote, noting that the agreement still fell short in other areas.

Fittingly enough, UAW dissidents have mounted their national challenge to the “old guard” in their union 50 years after rebellious members of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) made a similar political breakthrough. Campaigning as part of an insurgent group called Miners for Democracy (MFD), three coal miners challenged national union officials guilty of corruption, cronyism, and collaboration with management as bad, or worse, than in the UAW of recent years. Their unprecedented December 1972 victory—and its turbulent aftermath—remains relevant and instructive for modern-day union reformers, because the MFD experience shows that ousting incumbents is just the first step in changing a dysfunctional national union.

MFD candidates Arnold Miller, Mike Trbovich and Harry Patrick were propelled into office by wildcat strike activity in a union whose 200,000 members had a culture of workplace militancy without peer. Their campaign also benefited from years of grassroots organizing around job safety and health issues, including demands for better compensation for black lung disease, which afflicted many underground miners.

Although none of the MFD leaders had ever never served on the national union staff, executive board or any major bargaining committee, they defeated UMWA President W.A. (“Tony”) Boyle, the benighted successor to John L. Lewis, who ran the UMWA in autocratic fashion for 40 years. As inspiring as it was at the time, this election victory also illustrated the limitations of reform campaigns for union office when they’re not accompanied by even more difficult efforts to build and sustain rank-and-file organization. Of all the opposition movements influenced by the MFD, in the 1970s and afterwards, only Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU) has achieved continuing success as a reform caucus, largely due to its singular focus on membership education, leadership development and collective action around workplace issues.

Different route to the top

But, by the late 1960s, there had not been a real contest for the UMWA presidency in four decades. This enabled Tony Boyle to become a compliant tool of the coal industry, unwilling to fight for better contracts or safer working conditions. Boyle was able to maintain internal control by putting disloyal local unions and entire UMWA districts under trusteeship, which deprived members of the right to vote on their leaders. Increasingly restive miners staged two huge wildcat work-stoppages protesting national agreements negotiated in secret by Boyle (with no membership ratification). In 1969, 45,000 UMWA members joined an unauthorized strike demanding passage of stronger federal mine safety legislation and a black lung benefits program for disabled miners in West Virginia.

Critics of a deeply entrenched union bureaucracy, with a history of violence and intimidation, paid a high personal price. When Joseph (“Jock”) Yablonski, a Boyle foe on the UMWA executive board, tried to mount a reform campaign for the UMWA presidency in 1969, that election was marked by systematic fraud later investigated by the DOL. Soon after losing, Yablonski was fatally shot by union gunmen, along with his wife and daughter, as Mark Bradley recounts in Blood Runs Coal: The Yablonski Murders and the Battle for the United Mine Workers of America.

Jock Yablonski’s martyrdom set the stage for a rematch with Boyle. It took the form of a government-run election, ordered after a U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) investigation of vote-tampering and misuse of union funds by Boyle’s political machine. The standard bearers for reform in 1972 were Yablonski supporters who created MFD as a formal opposition caucus a few months after his death. They also published a rank-and-file newspaper called The Miners Voice as an alternative to the Boyle-controlled UMW Journal.

At MFD’s first and only convention, 400 miners adopted a 34-point union reform platform and nominated Arnold Miller from Cabin Creek, WV as their presidential candidate. Miller was a disabled miner, leader of the Black Lung Association and former soldier whose face was permanently scarred by D-Day invasion injuries. His running mates included another military veteran, 41-year-old Harry Patrick, a voice for younger miners, and Mike Trbovich, who helped coordinate Yablonski’s campaign in Pennsylvania. Despite continuing threats, intimidation, and heavy red-baiting throughout the coalfields, the MFD slate ousted Boyle by a margin of 14,000 votes out of 126,700 cast in December 1972.

Propelled by militancy

The union establishment was deeply shocked and unsettled by this electoral upset. Not a single major labor organization (with the exception of the independent United Electrical Workers) applauded the defeat of Boyle, an already convicted embezzler, who was later indicted and found guilty of ordering the assassination of Yablonski. The MFD victory and its tumultuous 10-year aftermath has been chronicled by such authors as women’s studies professor Barbara Ellen Smith in Digging Our Own Graves: Coal Miners and the Struggle of Black Lung Disease, and the late Paul Nyden, a Charleston Gazette reporter, in Rebel Rank and File: Labor Militancy and Revolt from Below During the Long 1970s, a collection of case studies about the period’s labor insurgency.

As Nyden notes, the MFD’s grassroots campaign “channeled the spontaneous militancy arising throughout the Appalachian coal fields.” Before and after their election, MFD candidates had key allies inside and outside the union. Among the former, according to Nyden, were “wives and widows of disabled miners, wildcat strikers, and above all the young miners who were dramatically reshaping the composition of the UMWA.” Among the “outsiders” were community organizers, coalfield researchers, former campus activists, investigative journalists, and public interest lawyers, some of whom would later play influential roles as new national union staffers.

The MFD inherited a deeply divided organization, with internal and external problems that would have been daunting for any new leaders, not just working members suddenly catapulted from the coalfields into unfamiliar union headquarters jobs. In Digging Our Own Graves, Smith faults MFD leaders for deciding to “dismantle their own insurgent organization” because the “skeletal network of rank-and-file leaders” that was the MFD had “basically become the institutional union.”

“Many activists joined the union’s staff or became preoccupied with running for office in their new autonomous districts,” she writes. “The decision to disband the MFD had serious consequences, however. It left the new administration without a coherent rank-and-file base and it left the rank-and-file without an organized vehicle to hold their new leaders accountable.”

Democratized structure

The reformers elected in 1972 did succeed in democratizing the structure and functioning of the UMWA. They also revitalized union departments dealing with workplace safety, organizing, membership education, internal communication, and strike support (see Harlan County USA, an Academy Award-winning documentary, about one early test of the MFD’s commitment to fighting back, rather than selling out).

In the crucial area of national contract negotiations and enforcement, greatly heightened membership expectations were harder to meet. A 1974 settlement with the Bituminous Coal Operators Association (BCOA) provided wage increases of 37% over three years, a first-ever cost-of-living allowance, improvements in pensions and sick pay, strengthened safety rights and job security protection. But the new leadership’s approach to grievance procedure reform did not resolve the greatest point of tension between rank-and-file militants and those among them elevated to top union office.

In the mid-1970s, the underground miner tradition of direct action was still so strong that UMWA members regularly walked off the job over local disputes of all kinds. Their culture of solidarity enabled roving pickets to shut-down mines nearby, in the next county, or an adjoining state, even if a different BCOA employer was targeted and the conflicts involved were unrelated.

These wildcat strikes subjected the national union to potentially ruinous damage suits by coal operators seeking to enforce a much ignored “no strike” clause, which required most grievances to be submitted to binding third-party arbitration. In 1974, new UMWA negotiators did not press for an open-ended grievance procedure that might have turned such quick strikes into a more disciplined and legal tool for contract enforcement. Instead, they agreed to the creation of an Arbitration Review Board, which merely added another frustrating step to a dispute resolution process already backlogged and overly judicialized. As post-contract discontent mounted in 1975 and 1976, an estimated 80,000 to 100,000 miners joined unauthorized strikes for the “right to strike,” while also protesting federal court sanctions (fines or imprisonment) of strikers who ignored back-to-work orders.

A counter-revolution

Within the union, the conservative Boyle forces continued to be a strong obstructionist force on the UMWA executive board and in some parts of the coalfields. Frustrated by Arnold Miller’s shortcomings as a negotiator and administrator, the most promising MFD leader—Secretary-Treasurer Harry Patrick—mounted an unsuccessful challenge to his fellow officer in a three-way race for the UMWA presidency in 1977.

Re-elected with a former Boyle supporter as his running-mate, Miller became increasingly weak, isolated and ineffective. His erratic handling of national bargaining with the BCOA helped set the stage for a 111-day strike by 160,000 miners who had to battle both the coal operators and their own faltering leadership. Highlights of that 1977-78 struggle included two contract rejections and a failed Taft-Hartley Act back-to-work order sought by President Jimmy Carter, a White House intervention even more controversial than Joe Biden’s role in the current national rail labor dispute.

UMWA contract concessions in 1978 and 1981 made organizing the unorganized increasingly difficult. More coal production shifted to the West, where huge surface mines required much smaller workforces, which usually remained “union free.” In the meantime, the multi-employer BCOA began to fragment, leaving the UMWA with fewer and fewer companies with which to negotiate an overarching national contract. Even firms operating in the eastern coalfields started non-union affiliates or subsidiaries, in what was becoming a declining industry.

More competent, progressive leadership was not restored until a second-generation reformer, Richard Trumka, took over as UMWA president in 1982. Trumka defeated Sam Church, who replaced Miller when the latter retired, after multiple heart attacks, in 1979. Trumka had gained valuable experience in the UMWA legal department during the mid-1970s. He had been a working miner before going to law school and then returned to the mines in preparation for seeking union office. But even with steadier, more skilled hands at the helm—and an inspiring strike victory at the Pittston Coal Company in 1989 — the union entered a downward spiral of reduced membership and diminished organizational clout. In 1995, Trumka become secretary-treasurer of the national AFL-CIO and, 14 years later, its president until his death in 2021 at age 72.

As the UMWA reform struggle confirms, the road to rank-and-file power includes many potholes and more than a few detours along the way. If union members can create a durable opposition movement and effectively utilize direct election of top officers, even many decades of institutional stagnation can be replaced by uplifting periods of organizational revitalization. But struggles for union democracy and reform often face larger constraints, including downsizing and restructuring of the industry which employs those seeking to revitalize their union and improve its leadership. Auto workers in the UAW have long suffered from a less severe decline of their basic industry but now have a rare and exciting opportunity to turn a union reform victory into a longer-lasting embrace of new organizing, bargaining and strike strategies that would benefit both white-collar and blue-collar members.

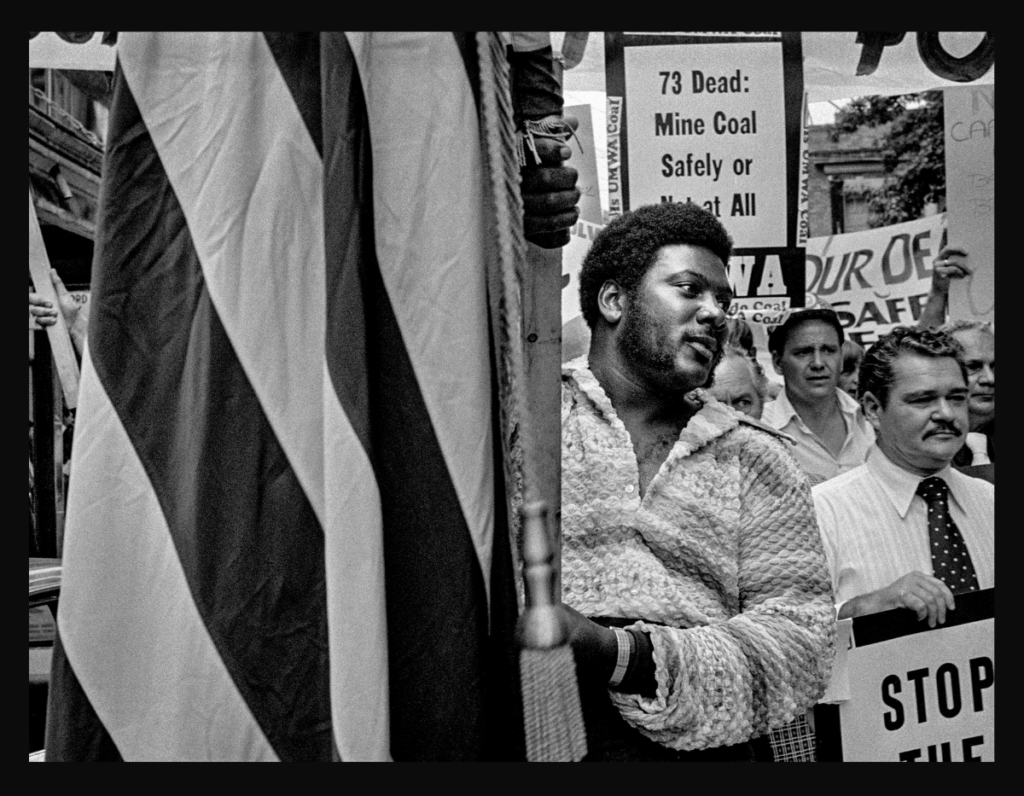

Featured image—Harlan County, KY 1974: A UMWA National Day of Remembrance for miners who had died in the pits. UMAW Secretary Treasurer Harry Patrick on far right with tie was one of the original members of the Miners For Democracy. Photo by Robert Gumpert, used with permission.

An earlier version of this article appeared on In These Times.

Did you enjoy this article?

We're in the middle of our annual fund drive, and this year we're building our own internal infrastructure for subscriptions, meaning more of every dollar pledged goes to fulfilling our mission. Subscribe today to support our work and be a part of Convergence's next evolution.