There was no disagreement within the new left during the 1980s about whether we should work on the Jesse Jackson campaigns of 1984 and 1988. Nor should it be a point of debate today about whether we participate in electoral politics. It was right for us to work on the Jesse Jackson campaign, just as many radical activists united with Bernie Sanders and worked for him in 2016. The goals for doing this in the 1980’s and 2016 are just as valid; to push the debate further to the left than the Democratic Party leadership was willing to entertain. In retrospect, both campaigns accomplished this although both Jesse Jackson and Bernie Sanders lost their primary challenges to the Democratic National Committees anointed candidates. These basic points are not in dispute.

The question for Rainbow Coalition activists and the post-Bernie Movement now is: did these campaigns help build the mass movement? Did they help build the left trend in this country? As evidenced by the dissolution of the Rainbow in 1989, and the League of Revolutionary Struggle dissolution a year later in 1990, the answer would have to be no on both fronts to these questions after 1988. For the Sanders campaign we may need to wait to answer this question until the 2018 mid-terms coming up this year or later.

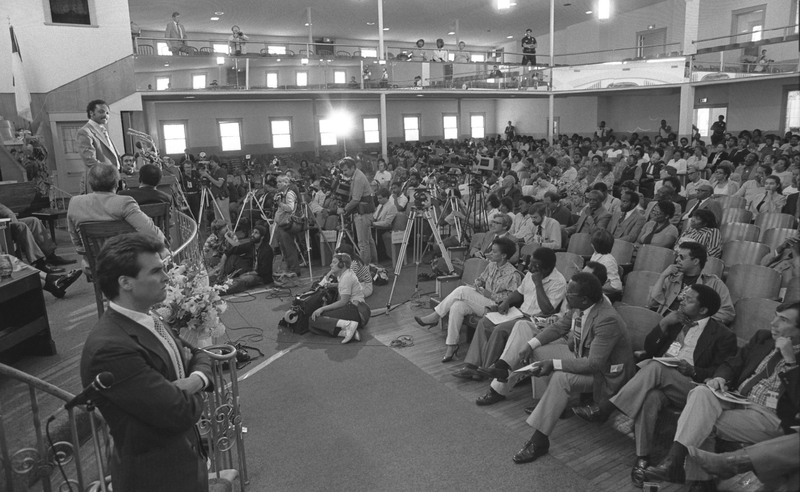

1984: A strong left roots Jackson in the grassroots

I worked on both the 1984 and 1988 Jesse Jackson for President Campaigns and was an open member of the LRS during my tenure. There was a big difference between the Jackson campaign in ’84 and ’88. In 1984 Jesse Jackson was less of a serious challenger and more of a messenger for progressives, including the African American community, that had seen the Democratic Party backpedal on all the gains of the civil rights movement won in the late 60’s and early 70’s. The new left organizations of the previous decade were mostly still in place during the 84 campaign, with a mass base in unions and communities of color. In 1984, many of the struggles Jesse Jackson was involved in that Bill Fletcher mentions in his “Lessons for today from the 1980’s Rainbow,” were the result of the left’s ability at that time to pull Jesse into struggles and in return give him reciprocal support for his electoral aspirations from places we had a base. For the LRS, this meant striking hotel workers, striking cannery workers, support committees for miners, and visits to Chicano barrios and Chinatowns. On college campuses he visited with Asian Students, Chicano Students in MECHA, and the Anti-Apartheid divestment and anti-sweatshop movements.

Jesse Jackson deserves credit for his leadership in embracing racial justice and class inequality, but without the left’s participation, he would not have received the breadth of exposure or the depth of analysis, nor in return receive as broad a reception as he received outside of the Black civil rights movement where he had historic ties. The left, including the LRS, also challenged the lack of proportional delegates Jackson was entitled to at the 1984 Democratic Party Convention held in San Francisco. As luck would have it, the San Francisco Bay Area was the national center of many new left groups including the LRS. As a few of our elected Jackson delegates entered the Moscone Convention Center, thousands rallied outside, demanding an equal voice, based on the votes cast in the 1984 primary. That convention changed the electoral threshold required to gain primary delegates, laying the groundwork for Jesse Jackson to become a serious contender in 1988.

1988: The demise of the New Left organizations & LRS

It would seem from the in-roads made in 1984 that the left would have had a bigger impact and made more significant gains in 1988, but while Jesse got more votes, the organized left and mass movements were much weaker after the 1988 elections. There were two trends we underestimated or ignored. First, this country was still moving to the right. Reagan easily trounced Mondale in the general election of 1984 and George Bush, likewise, dispatched of Dukakis in 1988. Worse, the Democratic Party was also moving to the right. I agree with Bill Fletcher on the left’s wishful thinking about the Democratic Party’s consolidation under the Democratic Leadership Council, which would usher in the Clintons and later accept Barack Obama. African American Democrats, elected into local office, would follow this trend. For those of us from San Francisco, Assemblyman, State Legislator, and San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown reflects this trend. By the 1980’s, Black mayors and Black municipal elected officials carried out the Democratic Leadership Council’s programs: attacking social safety nets, dismantling affirmative action and implementing the war on drugs, increasing the incarceration rates for Black and Brown people.

But the other crucial trend, which many of us in our left bubble did not realize until too late, was that while the right was on the rise throughout the 80’s, our New Left movement was on the decline. There was a big difference in what remained of the New Left between 1984 and 1988. The LRS lasted longer than most, officially dissolving in 1990. By the 1988 elections and definitely by the debate on the Rainbow’s future in March 1989, most of the New Left groups were gone. I didn’t know it at the time but the LRS was also in critical condition.

In 1984 I was a cook in a hotel in San Francisco, and an elected rank and file officer of Hotel and Restaurant Employees (HERE) Local 2. I pushed for Jesse Jackson’s endorsement in this capacity and as a delegate to the SF Labor Council. Most LRS members worked this way in some capacity or other. Most if not all of us were unpaid volunteers. By 1988 I was on as a full time paid organizer of the same Local. I got release time to go to work on the Jackson campaign as his Northern California Labor coordinator. I also went down to Houston to work on Super Tuesday. I worked as a full-time paid staff member of his campaign.

In 1984, the LRS was not alone in my union local; there were many cadres from various left groups in hotels and some restaurants all over the city. By 1988-89 all those organizations and by extension, their cadres were gone. In 1988, there were more leftist staff in Local 2, including from LRS, but our cadres’ anchoring our base in various workplaces were mostly gone. This was the beginning of the end for the new left organizations, coinciding with the 1988 Jackson campaign, creating the perfect storm.

Without a strong mass movement and base, the left is at a disadvantage in a united front electoral campaign

Why is this important? I joined I Wor Kuen (IWK), a predecessor of LRS in 1974. We were growing exponentially and expanding across nationalities and geographical areas. As socialists we believed we should be based in the working class. We targeted industries to go into. I half- jokingly tell people who asked why I went into culinary work that “it is because of my gender and race”. Chinese men have long anchored the kitchens in the hospitality industry of the San Francisco Bay. I could speak Chinese and this added to my ability to organize the majority immigrant workforce. I went into HERE, because I was asked/told to. I held working class jobs as a Teamster, but working in union warehouses was still better than union restaurant work, which was immigrant based work and I was American born. I had done restaurant work in high school and hated it. I swore I would never do it again – until I became a leftist. Besides strategically placing cadre in union industries, IWK also had the line that we could run for elected union office but not take appointed union staff jobs. We explicitly opposed people who had never worked in an industry taking on union staff jobs.

By the mid-80’s, we were having a harder time recruiting into the LRS. We changed the above policies slowly. First we started taking union staff jobs, but with cadre who had at least worked in the industry. This coincided with one area of recruitment that had not totally dried up: student work, especially in some of the campuses with an active anti-apartheid movement. Many new recruits in the 80’s came from some of the elite universities. Many factory and working class jobs in the 70’s were filled by student radicals who came off the campuses in the 60’s. The LRS student recruits leaving college in the 80’s would not consider going into factories or low level service work. They did however consider going directly into union staff jobs, work as legislative aides or on campaign work with politicians. They also moved directly into municipal government jobs, another position we opposed in the early days of IWK. We felt it was difficult to fight city hall when you work there.

Some members in the national leadership of the LRS, in particular Asians from the IWK, also had ambitions to move on from revolutionary work and their educated backgrounds gave them rapid entre to Jesse Jacksons upper-echelon staff positions. The exceptions they made for the younger cadre of the 80’s on college campuses like Berkeley and Stanford fit in nicely with their own aspirations to move on. Many of the top national and regional staff positions in the ’88 Jackson campaign were occupied by not just members of LRS, but Asian Americans, formerly of IWK. This is one reason we sided with Jackson on the dissolution of the Rainbow into his personal campaign organization in 1989. His top staff members would stay with him, or with his blessing, go into local electoral campaigns of their own. This was not unique to LRS cadre. Many former members of CWP, CPML, LOM, etc. ran and won local offices after the 1988 campaign or got jobs as legislative aids or took positions as municipal bureaucrats.

San Francisco Mayor Ed Lee, an apprentice of Willie Brown was one such example. He played on his background as a lawyer for tenants in public housing but never acknowledged any claims to the Asian American radical left, where much of that struggle for tenants was incubated. Why would he? As a city functionary for three decades, and finally Mayor, he followed in Willie Brown’s foot-steps. In spite of its progressive imagery, San Francisco, under Lee’s leadership, continued policies of development-deals, fast tracking gentrification, tax-breaks for the newly minted billionaires in the tech sector, continued police violence against the Black and Brown communities, and street sweeps against the homeless. Ed Lee died suddenly, last year while in office, and some remnants of the left and progressives lined up with the Chamber of Commerce, developers, and tech giants to mourn his passing.

In summation, the left must work on electoral campaigns – better Democratic candidates can move the needle of popular discourse. This is not in question. In power, progressive and liberal political officials can also soften capitalism’s attacks against the poor and oppressed minorities. This should also not be debated. In the 70’s we even saw some moderate reforms. But, we should be realistic. We won’t hold anyone accountable, not even former leftists, unless the mass movements on the grass roots level continue to grow and organize. They won’t grow through elections. In this regard, the history of electoral politics has not been kind to the left.

Did you enjoy this article?

We're in the middle of our annual fund drive, and this year we're building our own internal infrastructure for subscriptions, meaning more of every dollar pledged goes to fulfilling our mission. Subscribe today to support our work and be a part of Convergence's next evolution.