“I’ve dreamed of this moment since I was a little girl,” India Walton said when she announced her run for mayor of Buffalo in December 2020. “I’ve always wondered what it would be like if someone in City Hall cared about me or what I wanted.”

That dream might have seemed far-fetched. An unknown nurse turned community organizer, who grew up on Buffalo’s East Side in a working-class family, was going to take on a deeply entrenched political machine and win: in what world? Mayor Byron W. Brown—a career politician with every advantage—didn’t take it seriously. And it cost him.

India Walton stunned the mayor, and everyone else. With her victory, she was poised to become the person in City Hall that she had always wondered about.

But the story had an unfortunate end.

Byron Brown reversed his fate by refusing to concede the race to Walton. Instead, he launched a seemingly desperate write-in campaign with the encouragement of political elites, such as ardent Trump supporter and real estate developer Carl Paladino. It turned out to be a successful strategy after all. When all the votes were counted, Brown had won with 38,338 votes to Walton’s 25,773. Not only did he win a fifth term, becoming the longest-serving mayor in the city’s history, but he joined the exclusive company of Lisa Murkowski, who used this strategy to retain her U.S. Senate seat in Alaska, and Mike Duggan who did likewise to become mayor of Detroit.

Brown won by diffusing the influence of the Democratic Party machine and engaging the city’s business elites, by courting the right wing and painting Walton as an extremist. The missteps that cost the Walton campaign dearly could be chalked up to inexperience—another of Brown’s major appeals to voters. Still, Walton won in key Black and working-class neighborhoods, and the multiracial, intergenerational, gender-inclusive coalition that came together behind her transformed Buffalo’s political map.

Brown mobilizes the elites

While most people thought the write-in campaign was a fool’s errand at first, the weeks and months following the primary showed that it was anything but. The Brown campaign was able to organize the business elite, for-profit developers and real estate lobby, and several Democratic politicians quickly and methodically. He did so by appealing to their political leanings and ambitions, known in organizing as self-interest.

Additionally, Brown did what most wouldn’t do. He courted the GOP, accepted significant donations from individual Republicans, and benefited from independent expenditures by the New York Republican Party. Available data suggests that Brown won near universal support among registered Republicans in the city.

The Buffalo Police Benevolent Association (PBA) also endorsed Brown during the general election. The president of the Buffalo PBA said, “There has never been an easier choice for mayor.” In a conservative Democratic city like Buffalo, the call to “Defund the Police ” or align with defund’s proponents can become a death knell for political campaigns.

The Buffalo PBA and the Brown campaign exploited Walton’s organizing and advocacy during the racial uprisings in Buffalo and across the country after the murder of George Floyd. As Buffalo ranked 12th worst among 79 mid-sized cities for violent crimes, the Brown campaign painted Walton as a candidate who, if elected, would make Buffalo less safe. It released a campaign ad with a handful of Buffalo police officers endorsing the mayor. The message: Buffalo police will lose their jobs and Buffalo will be thrust into a state of anarchy.

The Walton campaign didn’t have an immediate response to the attack ad. In the absence of a rebuttal, the question lingered: Would Buffalo become less safe? By the time the campaign had raised enough funds for their own ad, it was too late. That ad began to change voters’ perception of the two candidates. South District, home of a disproportionate number of City of Buffalo employees, including BPD officers, reflect that reality: Walton received a meager 1,395 votes in South District as opposed to Byron Brown’s 7,724.

Corporate media backs brown

The Buffalo News’s publisher and president serves in a leadership role in the Buffalo Niagara Partnership (BNP), as did his predecessors. BNP, the “area’s chamber of commerce and privately-funded economic development organization,” has pulled the strings behind the scenes to shape the city policy under the 16 years of Byron Brown’s administration.

The BNP funneled tens of thousands of dollars to the Brown campaign through its political action committee and individual donations from its corporate members and their executives. The News aided these efforts through its skewed election coverage, which frequently crossed the line from bias toward the powerful to outright misinformation and unverified character attacks.

In the runup to the Nov. 2 election, Our City Action Buffalo and city residents took action to hold The Buffalo News accountable for its flaming bias. Their mini-campaign led to publication of a couple of pro-Walton articles and op-eds.

Two media outlets consistently provided voters with an alternative perspective throughout the race: The Challenger, which endorsed Walton for mayor, and Investigative Post.

The judge and the developer

Many times during the campaign, the connections Brown made over his time in office pulled through for him. Nowhere was this more obvious than in his ploy to get his name on the ballot in November, after initiating his write-in gambit.

Brown attempted to appear on the general election ballot by filing a petition under the newly created “Buffalo Party.” The commissioners from the Erie County Board of Elections denied the petition because the campaign failed to file before the May 25 deadline put forward by the state.

Byron Brown appealed the decision, and when he did, he won. Trump-appointed U.S. District Judge John L. Sinatra, Jr. ordered Byron Brown’s name to be put on the ballot less than one week before the state’s deadline to certify ballots.

Nick Sinatra, the judge’s brother, is a real estate developer in Buffalo. He and limited liability companies associated with him donated more than $11,000 to Brown between 2012 and 2021. In addition, Brown appeared in a commercial for Sinatra and Company Real Estate in 2018, praising the developer for his commitment to the city of Buffalo. The Brown administration also didn’t collect taxes from the real estate developer to the tune of $800,000 until the Public Accountability Initiative, a Buffalo-based research organization focused on corporate and government accountability, prepared a report and shared it with local media outlets.

The people won that day, but it could have just as easily gone the other way. Buffalo’s power structure closed ranks around its own, presenting the Walton campaign with huge institutional obstacles even as it strove to learn the ropes of electoral work.

Messaging missteps

Those within and outside of the Walton campaign, organizers and community leaders, politicos and pundits, and everyone in between has opinions about why the campaign ultimately failed.

During her victory speech after the primary, Walton made a messaging misstep that would haunt the rest of her race. “This campaign is only the beginning,” she said. “This doesn’t stop with me. We’re coming for all the damn seats.” That felt good to the faithful in the moment, but in a campaign debrief someone shared how deeply damaging the comment was. It alienated elected officials and leaders who would have otherwise been allies and moved their bases to support Walton as the Democratic nominee. The comment has been reiterated by others as well and points to a tendency to polarize that the left writ large must grapple with in a more nuanced manner to create viable campaigns in the future.

Defying traditional political wisdom, Walton veered left in the general election, embracing the term “socialist” in a way she hadn’t during the primary. Though she was the only candidate to have a detailed policy platform, many observers felt the campaign couldn’t leverage this to define the issues. Case in point: Walton’s top policy priority was “Getting Serious About Public Safety.” She talked at length about her approach, which was “evidence-based, data-based, and founded on proven practices in Buffalo and elsewhere.” And yet, she couldn’t shake the extremist label. By contrast, it took her campaign far too long to push Brown to defend his record.

Mechanics matter

Unlike Byron Brown, who got his political start with the political club Grassroots, started by a group of insurgent Democratic block club leaders, India Walton began her insurgent campaign with no political apparatus in place.

Soon after her primary win, her campaign manager was replaced with two co-campaign managers, but the relaunch of the campaign took longer than most anticipated. Time ticked away and elected officials, political strategists and operatives, as well as Walton’s supporters, began to wonder if the campaign was in crisis, not taking Brown’s write-in campaign seriously enough, or both. The local Democratic Party didn’t help: It took them more than 65 days to endorse their own nominee for mayor. The local Democratic Party didn’t help: It took them more than 65 days to endorse their own nominee for mayor. Prominent Dems from around the state came to campaign for her opponent or stayed out of the race altogether. At one point state Democratic Party Chair Jay Jacobs compared Walton to former Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke.

In mid-September when the Walton campaign replaced community-rooted, novice campaign managers with an out-of-town, professional campaign manager, it became clear that the campaign was facing some challenges, even though its messaging indicated otherwise. Multiple leadership changes led to perceived instability and uncertainty, and with only a month and a half until Election Day, people began to feel what the polls reflected: Brown was up, by a lot.

Not only had Walton’s campaign started from scratch, and bobbled a bit over the summer, but it was taking on a long-term project in a compressed time frame. The real relationship-building needed to move transformative politics can’t happen in a single campaign cycle. Going forward,

Buffalo’s new, emergent Left, like community organizers and activists all over, will be learning how to build power between elections that can be harnessed for the campaign sprints.

All this said, the Walton campaign still was transformative.

Elections help us build collective power

Our City Action Buffalo (OCAB) helped India Walton obtain an endorsement by People’s Action in March 2021, one of the campaign’s first major national nods. OCAB ultimately decided to organize independently so that it could complement the campaign’s work through strategic interventions. and coordinate with other progressive organizations locally, statewide, and nationally.

This involved weekly calls with Our Revolution, Roots Action, Democracy for America, Progressive Democrats of America and others who wanted to throw down to support the Walton campaign. Late in the cycle, the Working Families Party formed an independent expenditure campaign as well, after an independent poll showed, yet again, that Brown had a commanding lead over Walton.

This work culminated in a GOTV weekend for the Buffalo movement history books. In a former butcher shop in the heart of Buffalo’s West Side, in New York State’s most diverse zip code outside of New York City, OCAB set up a headquarters for their efforts. Partners such as Community Voices Heard Power and Black Voters Matter traveled across the state in vans for six to eight hours to participate.

During orientations, members of these organizations reflected that they came because if it can happen in Buffalo, it can happen in their place. Youth of color from across the city reflected the hope that they felt at the prospect of a mayor who shared their vision for the future. They were poll watchers, canvassers, and social media gurus who provided joyful content that attracted even more people to the cause. The energy and excitement was palpable throughout GOTV, with people constantly in and out.

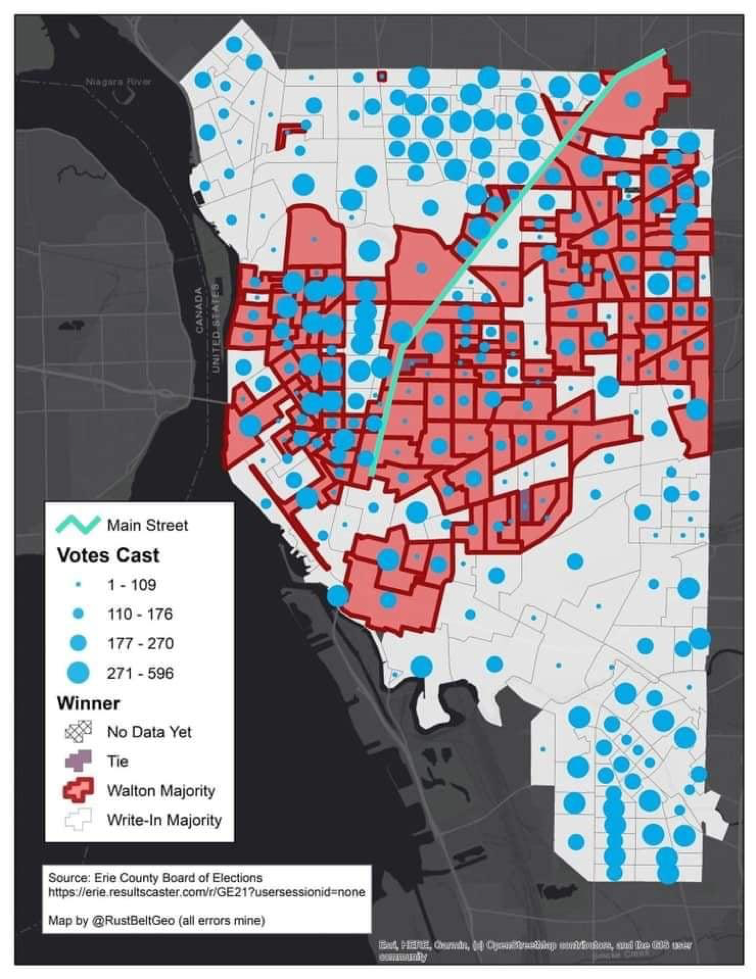

That weekend hundreds of shifts were covered and thousands of doors knocked. They focused their efforts, as OCAB had throughout the general election, in the Masten, Ellicott, Delaware, and Niagara districts. The first two districts are located on Buffalo’s East Side and represent Black, working-class voters. Delaware is Buffalo’s most affluent district, liberally minded in some parts and incredibly conservative in others–think California. Finally, Niagara is located on Buffalo’s West Side, and is home to immigrants, refugees, Black and Brown people, and white progressives. It is arguably the most progressive district in the city of Buffalo and the heart of Walton’s base. The combined efforts of the Walton campaign and OCAB secured wins for Walton in three out of four of the districts above, including Byron Brown’s home district of Masten.

Main street no longer divides us

Twenty years ago, Buffalo’s own Ani DiFranco wrote the song Subdivision with lyrics that hold true even today: “The Berlin Wall still runs down Main Street, separating East Side from West.” Community elder and founder of The Buffalo Latino Village Alberto Cappas evoked the same imagery in his op-ed in The News towards the end of the general election. “It’s time for Walton to tear down Buffalo’s Berlin Wall,” he wrote.

Even though she didn’t win the campaign, Walton connected the East Side and West Side in a way that had never happened before in a citywide election. The post-election map tells the story of a united East Side and West Side in common cause. For all the poltricks of the power structure and challenges with the Walton campaign throughout the election, one fact remains: The poor and working-class communities of color—specifically Buffalo’s East Side Black population—and white progressives could be the coalition that changes the face of politics in this city.

Did you enjoy this article?

We're in the middle of our annual fund drive, and this year we're building our own internal infrastructure for subscriptions, meaning more of every dollar pledged goes to fulfilling our mission. Subscribe today to support our work and be a part of Convergence's next evolution.