In early December around 100 people crammed into a church in downtown Buffalo for Our City Buffalo’s fifth annual Anti-Displacement Summit. Community and cultural organizers, policy experts, interpreters, Indigenous elders, writers and poets, parents and youth, and all kinds of Buffalonians educated themselves and each other on policies and community-rooted solutions to protect long-time residents and communities of color from the negative impacts of profit-driven economic development.

Displacement weighs heavy on the hearts and minds of residents every year around this time. It was more pronounced at this year’s summit, as the human toll could – literally – be counted. The first anniversary of the 2022 Buffalo Blizzard was about to arrive, much as the blizzard itself had, without much fanfare or forethought. More than 47 people were victims of the erosion of services and the continued impact of ever-growing displacement. This displacement, like all displacement, was preventable, the result of government underpreparedness and inaction.

“Buffalo failed us. It failed a lot of people. It failed a lot of families – brothers, sisters, mothers, friends. It’s devastating and disgusting…it’s disgusting that it took a year to remember all the names,” lamented Edie Syta, whose mother died trying to buy fish from the Broadway Market for Christmas Eve dinner. Her mother, Stasia Syta, was an immigrant from Poland who didn’t speak English, and wasn’t informed by authorities about the severity of the storm.

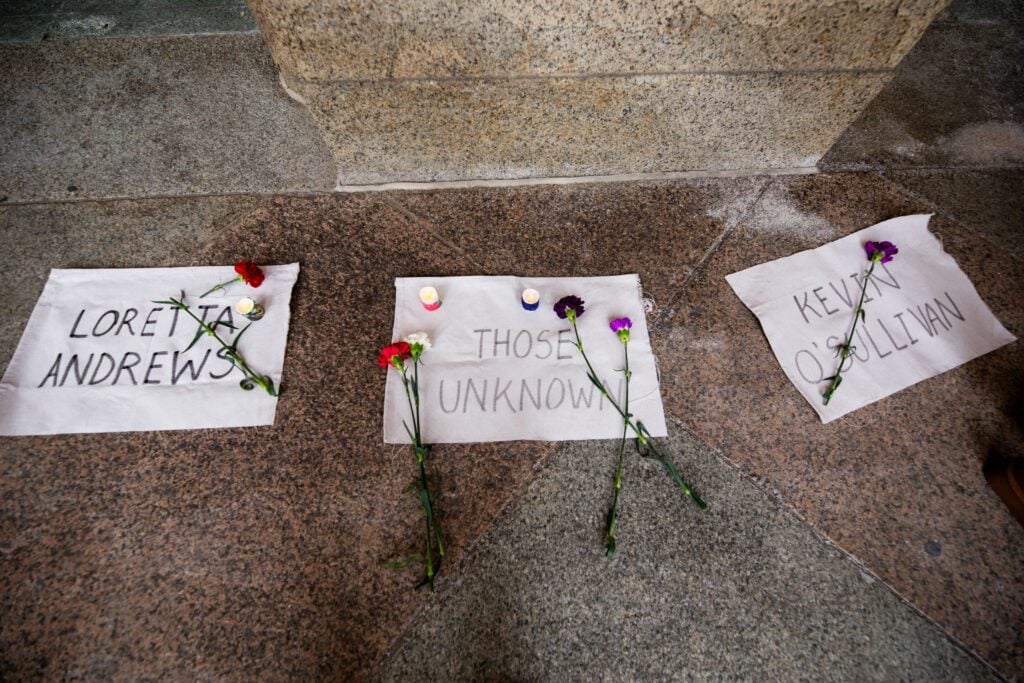

Edie was one of dozens of family members, loved ones, and community members who silently marched down Delaware Avenue from the Summit to City Hall in a community-led, public memorial for the victims. The first and only. With tears, flowers, deep breaths, libations, lights and banners bearing the names of all those known and unknown, the community remembered.

City of Good Neighbors

This has become the new norm in Buffalo. The community meets the moment, time and again. They respond with their whole chest and an ever-expanding mutual aid network. Buffalonians have always had a reputation for helping each other. That help has become systematized over the years, born out of years of union, community, and faith-based organizing, and, more recently, a white supremacist mass shooting and a catastrophic blizzard. Meanwhile, elected leaders have settled on a predictable strategy to abdicate their responsibility: Refuse to acknowledge the harm that has been caused and maintain the status quo, or, in more extreme circumstances, fill the void with empty promises and wordy platitudes, with full confidence that the community will either forget or move on.

But the community hasn’t forgotten or moved on. In fact, Buffalonians are coming to terms with the fact that they must support each other and contest for power at the same time. This on top of everything else feels heavy, overwhelming, and unsustainable. As a result, the movement to build enough power to self-govern has had many stops and starts over the past couple of years.

It might be a new year but as we closed out 2023, Buffalo was still reeling from the trauma and pain of 2022. That year began like others do, but things drastically changed on May 14th. A white supremacist shot 13 people at a grocery store on the East Side, murdering 10. The city’s dishonorable claim as one of the most racially segregated metropolitan areas in the United States became more than a statistic that day.

The Buffalo-based think tank Partnership for the Public Good had released a report entitled A City Divided: A Brief History of Segregation in Buffalo in April of 2018, almost four full years prior to the Tops massacre. It told a familiar story to those who live it every day. It itemized the far-reaching costs of segregation on people of Hundreds of residents participated in public hearings, Council meetings, and other forums to make their voices heard. Thousands more spoke out against the gerrymandered districts over the course of the next several months. They raised their voices about the need to confront systemic racism now, not repeating the mistakes of our past and waiting for another generation to begin to address the flagrant harm.

Less than nine months later, while the grief and trauma of May 14th was still raw, tragedy would strike again. This time in the form of a blizzard, the likes of which had been felt and experienced by Buffalo before, but not for at least a generation. The total accumulation from December 21st through December 26th, 2022 was 51.0 inches (or 4.3 feet), and included hurricane-force winds of up to 80 miles per hour, wind chill temperature of negative 30 degrees, and whiteout conditions. Starting on the 23rd, parts of the city of Buffalo experienced almost two full days of zero visibility.

The blizzard and lake-effect snowstorm paralyzed the region, hindered holiday travel and canceled Christmas celebrations, knocked out power for more than 100,000 people, temporarily put an end to all emergency services in the city, and left more than 47 community members dead in Erie County; 31 of those were in the city, and 20 of those were people of color.

People were stranded on their way to run errands that would’ve taken only a few short minutes under normal conditions. Roads were impassable. Desperation led Buffalonians to defy the travel ban and unsuccessfully try to make it to vulnerable family, friends, and loved ones—sometimes with tragic consequences. Anndel Taylor, a 22-year-old member of 1199SEIU, died on a stretch of highway connecting the suburban town of East Aurora, where she worked at Absolute Care of Aurora Park, to the city of Buffalo where she lived. Abdul Sharifu, a 26-year-old Congolese father-to-be, was killed when he ventured out into the storm to buy milk for a neighbor’s baby. “Trying to bring a gallon of milk home to a friend cost him his life,” recalled his friend during the remembrance in front of City Hall.

However, the response from the City of Good Neighbors was equally dramatic and moving. There was a 70,000-person Facebook group that verifiably saved lives, started by two people who feeling powerless, decided to connect people. Up and down main arteries and side streets across the city, people looked after each other. The Buffalo Mutual Aid Network, Twitter/X, community organization and block club listservs, text group chats and Facebook status updates are full of documented instances of people coming to the aid of others. Folks shoveled each other out, provided groceries and supplies, performed wellness checks, saved pets and other non-human creatures, and risked their lives in the name of community care and collective action. Dozens of volunteers from the Black East Side community and Bangladeshi East Side community joined forces to save hundreds of Buffalonians, providing them with transportation, food, water, shelter, and other basic needs. A Buffalo couple even sheltered a deceased woman’s body in their home until it could be collected by the authorities days later.

County and local elected leaders and officials were widely criticized for their ill-prepared and poorly managed response to the storm. Erie County Executive Mark Poloncarz defended his decision to wait to enact a travel ban. He openly condemned Buffalo’s Mayor Byron Brown for his handling of the Buffalo blizzard and storm cleanup efforts, calling it “embarrassing,” in one of the most memorable moments of the 2022 Buffalo Blizzard. He also revealed that Brown hadn’t been on daily coordination calls with other municipalities. Both were held accountable in the court of public opinion for not informing people further in advance or having a definitive plan to keep people safe during a life-threatening storm.

Instead of reallocating funds to make sure that people had what they needed during the storm, the City’s limited resources went into the immediate creation of an anti-looting detail. The day after Christmas, Mayor Brown held a press conference where he chastised Buffalonians who broke into businesses during the storm, referring to them as the “lowest of the low.” The new anti-looting unit expanded the reach of the Buffalo Police Department overnight. It was reported that 10 people were arrested mere days after the detail was created. “You’re destroying your community. It will not be tolerated,” Buffalo Police Commissioner Joseph Gramaglia said. “We’ve made it a priority to each of our district detectives. We will put your face on TV.”

City of No Illusions

“We are all we have” isn’t just a subversive or anarchic political slogan. It’s a phrase that I’ve heard repeated over the past 12 months in the most unlikely places in Buffalo and by the most unlikely of sources. For the majority of Buffalonians it’s how they’ve always felt–though it does seem to be more acute after a year filled with death and trauma (2022), followed by a year of non-acknowledgement and the political elite scurrying like rats on a sinking ship to leave their current office (2023).

In the aftermath of the deadly blizzard, in which most – if not all – of the blame from the community’s perspective was placed squarely on City Hall, Mayor Brown requested an independent study from New York University’s Robert F. Wagner School of Public Service. After months of interviews and anticipation, a 170-page report was released in the sweltering heat and sunshine of Summer 2023. It chronicled the failures of the City of Buffalo and other governmental actors. It also made pointed recommendations for how the City could improve its emergency preparedness and responsiveness for next time. The list included such obvious items as adequate equipment, effective communication with the public, coordination of road closures, and equitable distribution of resources in neighborhoods throughout the city, not neglecting the poorest neighborhoods and those most in need. There were also personnel recommendations–a fleet manager and emergency manager, for starters.

If only things were that easy in Buffalo. Because the city has a strong-mayor form of government, the Mayor’s sign-off was needed for any of NYU’s recommendations to actually be implemented in a real way. That’s difficult for many reasons, chief of which is that there’s no money. Over the years, the Brown administration has balanced the budget with unrealistic revenue projections, borrowing from Buffalo Public Schools and spending down the City’s reserves.

Due in large part to an unprecedented amount of American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) dollars from the federal government, $331 million to be exact, the City of Buffalo has been able to fill budget gaps inconspicuously. Not unprecedented nationally but highly relevant for what’s ahead, Buffalo has spent about 50% of its ARPA dollars in this way. Those funds run out at the end of the year, and that means that the bills will begin to stack up and the revenue generation – namely raising property taxes – that Brown so harshly criticized his former political opponent India Walton for will become hypercritical (but not enough) in balancing the City’s budget. Rumors have been swirling about a return of the Buffalo Fiscal Stability Authority – the City’s control board – formed in 2003 to keep the City from going bankrupt.

Although the Mayor preferred not to include an emergency manager in the final 2024 budget, it was successfully negotiated by the Common Council. The position would have never been filled except for the fact that the Mayor took a public shellacking at the end of October, notably when he would have still been in the running for a new job as the president of Buffalo State University.

As the City’s snow plan was being finalized, University District Council Member Rasheed Wyatt mounted a one-man protest and refused to vote “yes” for any other hires for the City of Buffalo until the position was filled. Giving credence to his position, a former emergency management expert in New York City who reviewed the plan, speaking in an interview with local media, said it was “doomed to fail” without the City of Buffalo having its own emergency manager. An offer was made to a prospective candidate days later.

That debacle is consistent with what organizers, activists, and BLIPOC working-class Buffalonians have experienced over the course of the Brown administration. That’s why they fought so hard to try to elect India Walton mayor in 2021. Her election would have given the people the opportunity to govern and control public resources for the good of all–reversing the current practice of prioritizing profits for private developers and corporate landlords, maintaining the political and personal power to fail upwards.

That’s why recently Our City Action Buffalo and other community anchor institutions and organizations have decided to apply greater emphasis on an outside-inside strategy. This strategy builds the social and political capital and infrastructure needed to change material conditions for people on the ground while still holding elected leaders accountable.

A blizzard-related example of how the community has become more sophisticated in its approach is through self-organizing meetings, workshops, summits, and other popular education opportunities to share community resources (community fridges, snow brigades, etc.), develop community emergency plans, and present life or death information for the next extreme weather event. The community has taken this on independently while also keeping a watchful eye on City Hall, advocating for disinvestment from the over-policing of Black and Brown communities, investing greater public resources in warming shelters, climate catastrophe mitigation projects, interpretation and translation services to better communicate with Buffalo’s diverse and ever-growing population, and implementing other recommendations contained within the NYU report.

City of Healing and Redemption

In a climate-impacted city such as Buffalo, it was only a matter of time until the next storm took place. This past weekend’s lake-effect snow pummeled the Buffalo area, reminding residents of the horrors of one year ago and providing state, county, and local officials with a mulligan of sorts: to prove through actions that they had learned valuable lessons and were better prepared and more aware of the dire consequences for ineptitude.

State and county officials were aggressive in their approach, putting travel bans in place early and keeping them there for the duration of the storm. The only time they faltered in this approach was when Erie County Executive Mark Poloncarz announced that county residents who wanted to shovel at the Bills stadium were exempt from the travel ban. They utilized the emergency alert system twice to warn the public of the life-threatening storm, and provided regular updates to the public on what they could expect. New York State Governor Kathy Hochul’s successful negotiation to postpone the Buffalo Bills playoff game from Sunday to Monday was met with controversy outside of Buffalo but not (much) within it. She had heard her constituents’ cries of outrage at the handling of the last blizzard and did what needed to be done to quell them this time. And although it was clear that the state and county were running the show, with the City of Buffalo mostly parroting talking points and boosting information provided by the county, there did seem to be a seriousness about the snow removal efforts this time around that didn’t previously exist. Today, Buffalonians are savoring the sense of relief.

At least for the moment. The question still remains: Will Buffalo be ready for more severe and less predictable extreme weather events? Buffalo residents are beginning to answer that question through collective action and mutual aid efforts, running movement leaders for political office, resisting the City’s neoliberal policies, and showing up at City Hall to speak truth to power when it matters most.

Buffalo-born trauma therapist Nicolalita Rodriguez co-emceed the memorial for blizzard victims in Niagara Square on that unseasonably warm day in December. After everyone had spoken and the last note of “A Change is Gonna Come” had been sung, she stepped up to the mic and said, “Every one of these people has a story. They’re not just a name. We treat trauma as an individual and inevitable occurrence. We offer our sympathy, business as usual, like our City did. As a trauma therapist, I can tell you that this trauma is collective. Collective trauma requires collective healing.”

In the coming year, Buffalonians will attempt to heal. The only way that can happen is by rejecting cynicism that keeps us unorganized and choosing hope through collective action. If displacement, segregation, poverty, and climate catastrophe are all policy-driven phenomena, then by out-organizing the opposition Buffalonians can prioritize the passage of policies that create a truly equitable, inclusive, climate-resilient, and democratic community.

“The onus should not be on individual people. This trauma is systemic. The deaths of our loved ones could have absolutely been prevented,” Rodriguez continued, “In honoring the lives of those we’ve lost, we stand together to let our City know, we reject your sympathies. For any kind of healing process to begin, we need empathy and that starts with accountability.”

That’s why we’ll be drawing down power from those who would seek to skirt accountability and not commit to co-governing with the people. The new year brings new campaigns, and alongside policies, we’ll take aim at the very levers of power, by deepening and expanding participatory governance and community self-determination, by amending the current corporate charter, which concentrates power for the establishment, with one that is firmly grounded in community and human rights.

For more information on the ongoing organizing for justice and democracy in Buffalo, check out Our City Action Buffalo.

Featured image: December 2023 memorial for victims of the Christmas Blizzard of 2022 in Buffalo. Photo by Nathan Peracciny.

Did you enjoy this article?

We're in the middle of our annual fund drive, and this year we're building our own internal infrastructure for subscriptions, meaning more of every dollar pledged goes to fulfilling our mission. Subscribe today to support our work and be a part of Convergence's next evolution.