Seven days a week, all year long, you can find a sprawling open-air market on Chicago’s West Side. Vendors at the unpermitted market offer a range of services and sell everything from food and housewares to cigarettes, movies and CDs, often much cheaper than elsewhere. The market is the crossroads of Chicago’s informal economy—the survival economy for a majority of the city’s Black residents.

On the Jan. 27 episode of Frontline Dispatches, Richard Wallace of Equity And Transformation (E.A.T.) opened a window on the informal economy. “The informal economy is where you land when you’re told you can’t get a job here because you have a background, so it’s tied to the prison-industrial complex. It’s where you get hip-hop, jazz, it’s where our people have used their creativity to get some form of wage or income for themselves… when they are boxed out of the economy.” Informal workers not only sell at the market. They also do house-cleaning, childcare and elder care, style hair and wash cars, work as handymen and movers, and a range of other things. Their work helps them survive, just barely, and helps the larger Black community survive through the affordable services they provide.

Founded in 2018, E.A.T. aims to “build social and economic equity for Black workers engaged in the informal economy.” The organization released its report “Survival Economies: Black Informality in Chicago” in late January. With documentation and stories, the report breaks down the who, what and why of Black informality, locating it “at the nexus of systems failure.” Racialized exclusion from the job market, disinvestment in neighborhoods after manufacturing fled, punitive welfare “reform,” and everyday enforcement of “the New Jim Crow” all contribute. Below is the forward Richard Wallace wrote for the report. You can read the full report here.

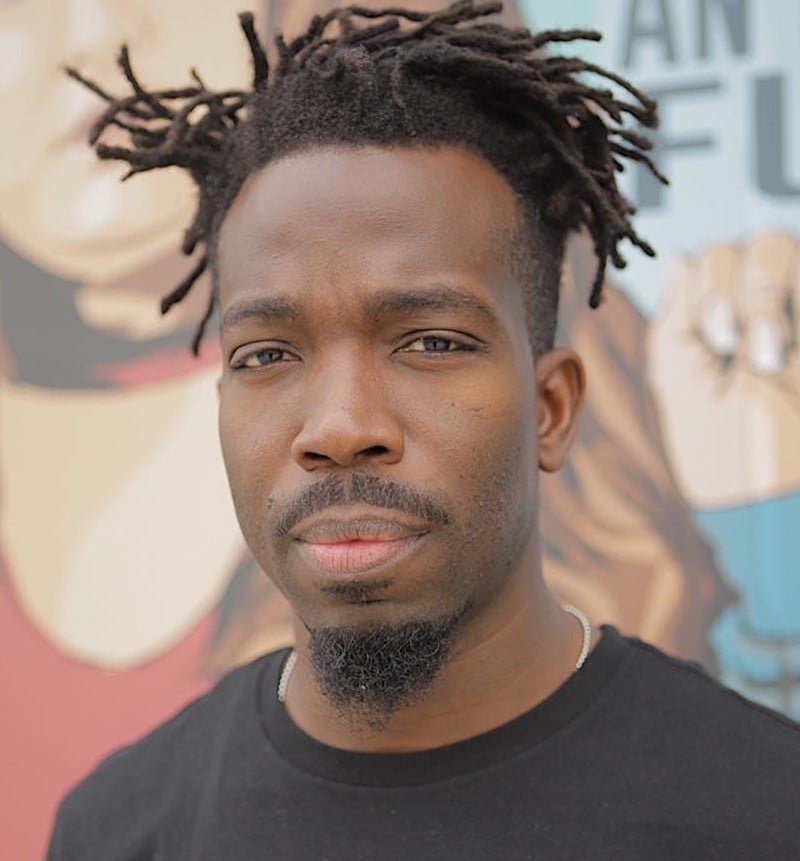

I am the founding executive director of Equity and Transformation (EAT). Our mission is to build social and economic equity for Black informal workers. For years I worked as a labor organizer and watched intervention after intervention fail to reduce the racial wealth gap or the unemployment gap for Black workers in Chicago. Persistent inequality led me to seek answers about how Black people in Chicago were surviving, even in the absence of an essential resource—regular, full-time employment. What I found was that Black people face systemic challenges. Their earnings are low. Their work is often criminalized. And as a result, the lives of Black informal workers are inherently at risk.

But I also found that Black informal workers are resilient and creative, and they have constructed an informal economy to acquire a means of subsistence. They have made lemonade out of lemons and are light years ahead of what policymakers define as alternatives to formal employment.

I knew there would be pushback for developing an intervention for Black informal workers because this isn’t traditional labor organizing. In fact, to date, EAT is the only organization in the US that focuses on Black informality. This is alarming considering the fact that nationwide Black people have an unemployment rate more than double that of their white counterparts. If Black workers cannot gain access to formal employment, yet they must operate in a system that requires money to acquire food, water and shelter, then there must be an alternative system of survival. Whether it is anti-Black racism, social stigma or a misconception of true worker solidarity, the broader labor movement has ignored the struggles and activism of Black informal workers who earn their living in these survival economies.

The basis for this research report stemmed from a need to better understand what unemployed Black people are doing to survive. This question leads us to try to better understand informality and the survival economies that have been created in cities like Chicago. There is a broad understanding of what formally employed workers will need in times of crisis, but there is little or no information about what Black informal workers require. EAT’s mission is to not only understand the scope of the problem, but to develop tools to break down barriers of accessibility, now and for future generations.

In closing, I would love to live in a world where all people had equal access to labor and economy, but we are not there in the US, and it’s painfully evident in every employment and economics statistic that is reported. Until that happens, work must be done to understand the current conditions of unemployed Black people and to move that understanding toward a more just and equitable future.

Did you enjoy this article?

We're in the middle of our annual fund drive, and this year we're building our own internal infrastructure for subscriptions, meaning more of every dollar pledged goes to fulfilling our mission. Subscribe today to support our work and be a part of Convergence's next evolution.