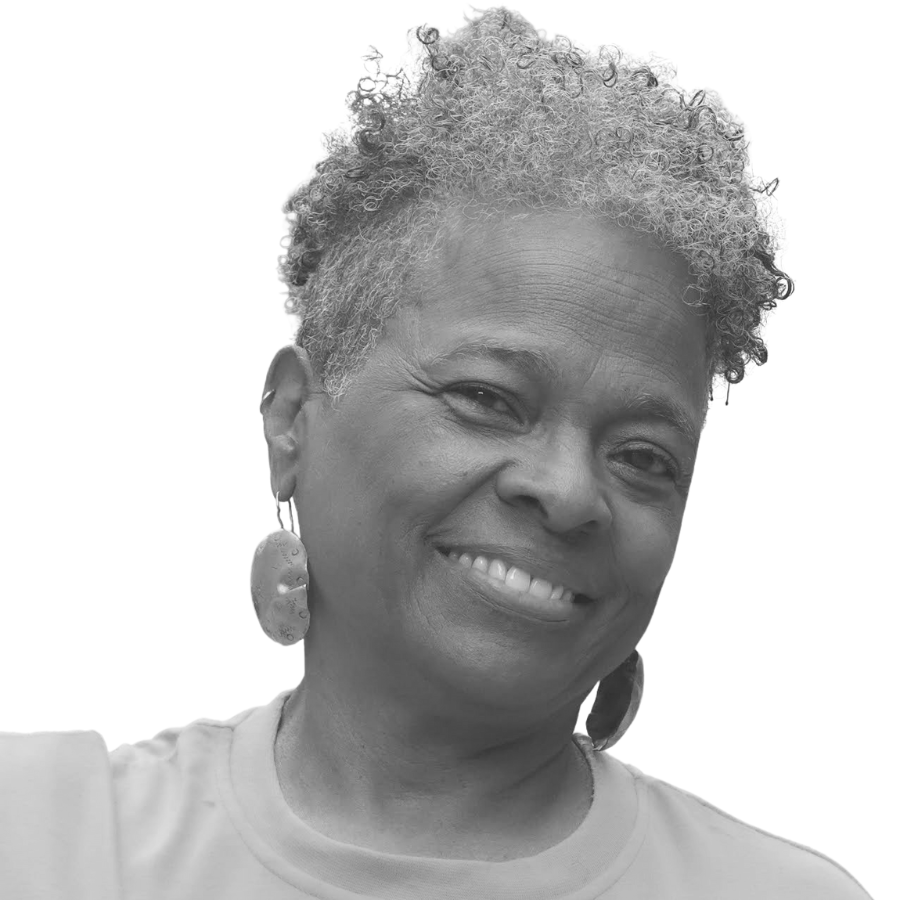

Fifty-six percent of people in the US who self-identify as Black call the South home. Today’s guest, Shafeah M’Balia, explains why and how we need to focus organizing strategies on Black workers in southern states. Shafeah is a lifelong activist and organizer with Black Workers for Justice and Muslims for Social Change.

In this episode Shafeah talks with host Jamala Rogers to help listeners understand why they need to move through lingering, harmful stereotypes of the South and understand the interconnectedness of all workers in the region’s supply chains. She’ll review her past and present efforts to organize southern workers, and explore why international solidarity with movements like that for a free Palestine matter to US workers.

[00:00:00] Shafea M’Balia: And they playing chess game and we the pawns. And so we’ve been, you know, arguing about whether or not we should be in solidarity with Palestine or we should be in solidarity with, you know, Trinidadians fight for reparations or Palestinians fighting against, you know, for their own country back. And they’ll use that as a way for us not to understand that we are also paying for that.

[00:00:24] It’s our money that is paying for those bombs that are being dropped. But we ain’t [00:00:30] got no healthcare. Homelessness is increasing exponentially, you know, across this country. And nobody, and that’s not being addressed.

[00:00:47] Bianca Cunningham: Welcome to Black Work Talk. The podcast voice of Black workers, leaders, activists, and intellectuals exploring connections between race, capitalism, labor, and culture, and the struggle for democratic, progressive governing power. [00:01:00] I’m your host, Bianca Cunningham.

[00:01:02] Jamala Rogers: And I’m your host, Jamilah Rogers. episode I’ll be joined by lifelong activist and organizer with the Black Workers for Justice, Shafia Mbalia, who’s going to discuss the importance of organizing Black workers in the South, why worker solidarity should be extended to the movement for a free Palestine, and much, much

[00:01:22] Shafea M’Balia: more.

[00:01:25] Jamala Rogers: So on episodes. of Black Work Talk, we will spend a lot of [00:01:30] time in conversation with folks who are already organizers in the labor movement. There are also people who are coming into this movement as new workers, and we want to make sure that those who are interested. And wanting to engage and organize, uh, know how to do that, because one of the things that I think we need to minimize is, is the number of mistakes that can be made as you sort of build your committee and move on to creating a [00:02:00] union.

[00:02:00] So there are a number of. So we’re going to talk about some of the tactics that we look at as we are building these committees and looking at how do you actually get to a union and here we are going to ask Bianca to share her insights about that. Bianca.

[00:02:19] Bianca Cunningham: Thanks, Jamala. So today we’re going to talk about building majority support.

[00:02:23] So. After you’ve had conversations with your co workers, you have a representative [00:02:30] committee, um, and have identified, you know, issues that everybody really cares about and is willing to, you know, move to, you know, change, you need to talk, start to talk openly and build your base. So, this is beyond even the committee or your initial trusted ones.

[00:02:48] Ideally, you and the committee have sat down and mapped out your workplace by name or department, right? Listed all the people out and gave somewhat of a blind assessment, if you will, of [00:03:00] where you feel like those folks are in relation to support for the union, normally a one being the most supportive. Uh, those are probably people who you’ve already spoken to or are really well aware of.

[00:03:10] Two, meaning people you don’t know or may be on the fence. Or three, meaning people who you know are going to be openly, uh, against the union. So in this phase, where you’re talking to your coworkers and building majority support through these one on one conversations, you want to figure out who are the best people to have you know, conversations with who based on relationships or [00:03:30] familiarity or the fact that we work next to each other, you know, whatever the case may be.

[00:03:34] And so you want to identify who are the best people to talk to the twos. And then you want to come up with a game plan to not be super explicit right off the bat in those conversations, but to be a little bit more vague. So just thinking about my own experience when I was having conversations with people who I wasn’t quite sure where they would stand, I started by asking them about the things that they care about.

[00:03:56] and setting out hypotheticals. So I never talked about a [00:04:00] union necessarily, but I talked about what would it look like for us to have power to affect some change in our workplace, whether that be over wages or benefits or even like, um, smaller practices, like how we take breaks. And so getting their feedback will let you know.

[00:04:17] whether or not they support a union coming in. So you want to really, you have to be actively listening and you also have to be calculating in your head at the same time that you’re listening, um, about where you’re going to [00:04:30] take the conversation. And so if you find that they’re very animated and that they feel strongly about some of the same issues that you all have identified or they’re, excited about the prospect of being able to affect change or take issues to them to management, then maybe you want to trust them a little bit more to talk about what those steps would be.

[00:04:49] If you find that they’re a little bit more afraid or kind of retracting or feeling uncomfortable in those situations, that’s probably an invitation for you to stop where you are. [00:05:00] And kind of bring it back to the group to assess how you would want to continue sharing information with that person. You might notice that I only talked about having conversations with twos.

[00:05:10] We should be completely ignoring the threes right now, actively, and also making sure that the twos that we’re talking to aren’t too close to some of those threes to go run tell that. So just being really, really, really careful about that. But in addition, once you’re having these conversations and another really great way to build support for the union is to [00:05:30] get your co workers to sign like some sort of like petition or a letter that states like what your key issues and goals are.

[00:05:36] For us, we had like kind of like a manifesto, if you will, where we talked about the importance of continuing the into the path of the civil rights movement by advocating for Black workers rights in our own jobs and in our own positions, right? And so we talked about standing on the shoulders of our ancestors, right?

[00:05:55] Um, and really like wanting to make things better for the greater good [00:06:00] of the employees in the company, not just for ourselves, something that we had every single person kind of sign. so that we can deliver it once we did get to some of the later steps, but it also kind of solidified by seeing other people’s names on the paper.

[00:06:13] It kind of grows and then you realize you’re not in this alone. And so it’s something to build momentum, but also to establish support. And then lastly, I just want to say that you legally only need 30 percent of people on cards. To file at the [00:06:30] NLRB, you need people to sign a card to say that they want to have an election to vote for a union.

[00:06:35] That’s the purpose of those conversations, right? But even though you only need 30 percent by law, any good union organizer would tell you, you need at least 80 percent because you’re going to have drop offs. Like people are going to get intimidated, back out, change their mind once the company starts their anti union campaign.

[00:06:52] So just something to keep in mind.

[00:06:54] Jamala Rogers: So, Bianca, a couple of things that I thought about while you were talking, because you talked, one of the things you said [00:07:00] was standing on the shoulders of our ancestors. And it may sound like this conversation is likened to runaway slaves. When you’re trying to get off the plantation and you have to be careful about who you talk to it’s not exactly the same thing But it’s the same Fear that’s guiding people and that is you don’t want to get in any trouble you are wanting to [00:07:30] Disassociate yourself with the folks who are planning these rebellions and these runaways.

[00:07:36] So, part of it is just self preservation. To your point, it’s like, those are the people that you’re not going to be engaged in. You know, these people would, you know of them already by some of the viewpoints that they’ve expressed in the break room, okay? So, you know that they’re going to be opposed to a union because they’re going up against, you know, the white establishment.

[00:07:58] That’s

[00:07:58] Bianca Cunningham: so interesting that you [00:08:00] liken it to that. I mean, I do think that people would say, you know, our current, uh, labor system is somewhat, somewhat of like a, you know, um, a system of slavery. Certainly not, not likening it to shadow slavery, but some sort of slavery, right? And I feel like this is also just like, to your point tied to survival, we need our jobs to survive and our jobs are tied to our ability to survive many times.

[00:08:24] And so that’s why that fear is so effective in this place because nobody wants to [00:08:30] lose their livelihood or their ability to provide for themselves and their families.

[00:08:34] Shafea M’Balia: Yeah. I just

[00:08:35] Jamala Rogers: think we have to be mindful of that.

[00:08:36] Shafea M’Balia: Those are not going to be the folks in your

[00:08:39] Jamala Rogers: inner circle where you discuss some strategy and tactics because they, they are going to.

[00:08:44] Um, so that people don’t have to be alarmed that even such things are happening. Uh, the other thing that I think is important is for people who may not be so fearful, um, as the people that we’re talking about, but who do have some reservations. [00:09:00] Uh, you know, the approach that sometimes I take with them is let’s get it on the ballot or let’s get it in front of folks and the petition.

[00:09:10] Uh, so that people have a right. To vote up or down and sometimes I found that that is effective because it doesn’t mean that you agree It means that you agree that we should have the right to for all of us to vote it up or down And uh that that has proved to be effective for some people because [00:09:30] they did not want to be seen As somebody that was stopping others because we’ve been talked to we’ve been taught about, you know majority rules so even if you are opposed to it, are you going to suppress the other voices that need to be

[00:09:45] Shafea M’Balia: heard or the other, uh, ways that we are trying to organize people.

[00:09:49] So I

[00:09:50] Jamala Rogers: always felt like for those people on the, on the fence, not like they’re scared or I’m gonna tell on y’all, but just needing a little bit of a nudge to be able to say, [00:10:00] We just want to get this in front of the workers, and your

[00:10:03] Shafea M’Balia: signing this will help get that.

[00:10:05] Jamala Rogers: If you decide later to vote it down, that’s

[00:10:07] Shafea M’Balia: your right to do that.

[00:10:08] But by that time, you have a

[00:10:10] Jamala Rogers: opportunity to actually engage them some more and

[00:10:13] Shafea M’Balia: solidify their support for a

[00:10:16] Jamala Rogers: union.

[00:10:23] So today on Black Work Talk, we are

[00:10:26] Shafea M’Balia: going to be having a

[00:10:27] Jamala Rogers: conversation with Shafia Mbalia. [00:10:30] And Shafia is a member of the Black Workers for Justice. She’s served many capacities in an organization over the last 40 years, uh, including, uh, being a founding member of the Women’s Commission. Uh, she’s a founding member of Muslims for Social Change, and she’s the Southern Regional Coordinator for the Imam Jamil Action Network.

[00:10:51] Shafea M’Balia: And

[00:10:52] Jamala Rogers: she’s the co director of the University. Uh, so you could see Working, organizing [00:11:00] workers is in her DNA. And so those intersections, believe me, she’s, she’s working on. So welcome to the

[00:11:06] Shafea M’Balia: show today, Shafia. Thank you so much Jamala for having me. Um, it is, it’s an honor. Um, and a pleasure to hang out with you.

[00:11:17] Yeah. Yeah, we

[00:11:18] Jamala Rogers: haven’t done it in a minute.

[00:11:20] Shafea M’Balia: Long time. Yes. And, and

[00:11:22] Jamala Rogers: I don’t, I feel even good that it’s, uh, via, uh, virtual. So I’m not going to even complain just being able to see you and hear [00:11:30] you. Uh, other than like email and that kind of thing. So, yeah, but you’ve been quite busy. Uh, and you were busy even before the Israeli attack on.

[00:11:40] on Palestine. So we’re going to get to that in a minute. Uh, but I really want, uh, the listeners to understand the strategic importance of organizing in the South and particularly organizing workers in the South. So can you speak a little bit to why that’s important and why that is a [00:12:00] dominant theme right now for a union and other labor groups, workers rights groups in the South?

[00:12:08] Well,

[00:12:09] Shafea M’Balia: let’s, let’s start with You know, what is the strategic role that the South plays both in the U. S. economy and even in the world economy? You know, what is projected about the South that it’s poor, ain’t got no money, that folks are ignorant, everything is [00:12:30] that it’s just, it’s just agricultural and, and all this other stuff and it’s, and it’s real, you know, some backwater.

[00:12:37] that has nothing to do with, um, you know, what’s happening in the world. And that couldn’t be further from the truth. Since the inception of the United States, it has, the south of the southern part of this, this, what is now called the United States, has played a pivotal role economically in both the development of [00:13:00] the United States and its history.

[00:13:02] And, uh, before that, but cotton played a major role in, in the development of the economy. And in fact, the exportation of, of cotton went into Europe. Britain in particular, was As much, if not larger than the rest of the economy, when you, when you put everything together, it played a humongous role in, in, in the um, the input of resources.

[00:13:29] And that does not [00:13:30] even include the question of slavery, in terms of the bodies, the labor, right, the sale of bodies, the breeding of bodies. The labor of our bodies, um, as, as, as black people, as enslaved Africans, that does not even include the, the monetary value of that, of those, the combination of those things into this [00:14:00] economy.

[00:14:00] Of course, while there was slavery in the North, there was slavery, you know, the, the importation of slaves and then the breeding of, the forced breeding of human beings was a major part of the economy of the South and contributed to the North. And in fact, you know, that, that, that, that question was the fundamental question that was really being fought over, you know, Lincoln care nothing about us.

[00:14:26] One of the few [00:14:30] things that Kanye said, right? They don’t care about you. And so, the economics of it, uh, is the growth of the country, period. The fact that Black people and enslaved Africans What counted as three fifths of a person had to do with the question of control of the South in Congress, in the U.

[00:14:52] S. Congress, so that what they called anti Beldon congressmen could control, you know, the important [00:15:00] committees and direction of the country. So from the very beginning, and of course, you know, the, the, the question of genocide of the indigenous people, you know, this place wasn’t always the United States, you know, this is a state apparatus that was, uh, created on top of peoples.

[00:15:21] And it is estimated, been said that there are as many people who were living on this continent as were in Europe at the [00:15:30] time. just in a bigger space. But we’ll, we’ll move forward and then look at, so you know, four of the busiest ports in the U. S. or in the South. Much of the military, the U. S. military, is based in the South.

[00:15:47] Charlotte and Atlanta are major world financial centers of banking. And so when you combine all of those things recently, uh, in fact, just this past [00:16:00] week with the United auto workers strike, you know, they talked about that, we could get into the. the strategy, which was just, was sharp, was, you know, we need to study that of what the UAW did and strengthen, strengthen those caucuses and all other unions that, you know, just turn stuff upside down.

[00:16:22] One of the key things that came out in a Democracy Now! interview with the, um, the president of UAW [00:16:30] is they talked about Not only the wages of the lowest paid workers, and we know who’s always the lowest paid. We don’t know who’s the first hired, excuse me, the last hired in the first fired. But on top of their their wages going up from something like 18 an hour to up to 40 in a few years, um, that the U.

[00:16:52] A. W. Is going to be going after the new push the new wave of of, uh, [00:17:00] auto branch plants and EV plants, right? Uh, the battery plants that are being, uh, constructed now that they’re going after those, those plants. And guess where they are? They’re in the South. Yeah, they’re across the South. And one of the things that Black Workers for Justice discovered in the work that we were doing is that, you know, many people do not understand that the auto industry, while, you know, the big three are based in Detroit [00:17:30] and, and have, you know, major plants in major parts of the country.

[00:17:34] But they have contracted out in their supply chain across the South, major, you know, plants and and workers because of the propaganda campaign, anti union, uh, propaganda war for decades that folks don’t understand that they are actually part of the auto industry. And so they think that they’re they think that they’re part of the bezel industry and the window [00:18:00] industry and the chair.

[00:18:02] You know, um, industry, but those different parts, um, all make up. The supply chain, you know, into putting together a car where I live in Savannah in Savannah, Georgia, uh, they’re getting ready for at least two battery plants, maybe three, um, in, in Southern and Middle Georgia. I think the third is a middle might be in North Georgia.

[00:18:27] I can’t remember right now. And so there’s a [00:18:30] major part that the South place inside the country, and then that international that economic. base has international ties around the world. And forgive me, I’m blanking right now. But in terms of, you know, you’ve got not just, you know, uh, Ford and GM, but you’ve got Nissan, you got Honda, you got Honda.

[00:18:55] Um, you’ve got all manner of, of, Uh, [00:19:00] international or global manufacturing companies that have major operations in the United States South. Why? Because there are no unions, because the union history is, is shallow. Folks don’t have that information. You know, there’s been this serious propaganda campaign waged and what, what states call business friendly.

[00:19:24] When they mean, when they say business friendly, what they mean is anti union.[00:19:30]

[00:19:35] Hi, this is Kayden, the publisher of Convergence magazine. There are a lot of places that you can put your hard earned money in support of our movements, but if you’re enjoying this show, I hope you’ll consider subscribing to Convergence on Patreon. We’re a small, independent operation and rely heavily on our readers and listeners like you to support our work.

[00:19:53] You patreon. com slash convergence mag. Subscriptions are pay what you can, but at 10 bucks a month, [00:20:00] you’ll get goodies as well as knowing you’re helping to build a better media system. One that supports people’s movements and fights fascism. And if you can’t afford it right now, don’t worry. All our shows will be free for you to enjoy.

[00:20:11] You can also help by leaving us a positive review or sharing this episode with a comrade. Thank you so much for listening.

[00:20:23] Jamala Rogers: So Shafir, just based on what you in terms of giving that history and [00:20:30] looking at The South geographical, uh, politically, and I’m thinking about, for example, what would make organizing workers down there much different from anywhere else in the country, just based on that history, the history of, you know, uh, low or no unionization, uh, the fact that you had white pathology helping to shape not only the mindset of [00:21:00] whites in the South, but blacks as well.

[00:21:02] So what kind of barriers did that create for organizing in the South?

[00:21:08] Shafea M’Balia: Well, we, we looked at, you know, thinking about the role that the South itself plays, you know, in the world and then looking at, you know, workers themselves and, um, you know, Malcolm X said that, you know, there’s an up South and a down South.

[00:21:28] Um, but there is a [00:21:30] real difference in, in a sense of, That the South has always been the bastion, the birthling, you know, of the most virulent racism. Uh, and, and that translates into, for example, um, even more of a A, uh, a struggle around leadership of, of, uh, of black workers, the question of more of a, a control by corporations [00:22:00] of the, of the business climate and, and of the propaganda machine.

[00:22:06] Um, the South is also has, it’s not surprising to see. You know, to go in a small town or between small towns and all of a sudden you’ll see a huge plant employing hundreds or thousands of workers and maybe they pay a little bit more than what’s being paid outside. That’s [00:22:30] what happened. Bessemer, Alabama, um, is that there was the threat, you know, which.

[00:22:39] Of shutting down the plant or or paying the wages of what is in the area And if it’s a matter of two dollars or four dollars or five dollars, you know more per hour You know, that’s a significant amount in someone’s paycheck Uh, and of course as I said the mess the question of racism and then and when you have plants [00:23:00] and manufacturing That is let’s say isolated from each other.

[00:23:05] You don’t have Neighborhoods like you might have in st. Louis Or in the large cities where the plant is located in a neighborhood people live nearby and so it affects the the thinking the organization of a neighborhood or community, you know, that’s all, you know, close together. And so it makes it that much more more difficult for [00:23:30] folks to see solidarity with each other, or to see how the, the, the plants.

[00:23:38] Existence there has a direct impact on their lives other than the paycheck. But what does it mean for the community? What does it mean for control of the local political system? The local political system in, in, in many of the smaller towns are much more vulnerable to the budgets [00:24:00] of, of corporations to have an impact.

[00:24:03] So they’ll, they’ll make a donation, you know, for playgrounds and churches and that are the kind of, uh, of donations that, that, um, they’re not used to getting. Um, and, and they have therefore much more of an impact on chambers of commerce. For example, well, you know, if you don’t like this, then we can move, you know, to move, um, and therefore [00:24:30] impact on a tax base, the, the question of, of workers isolation from each other is a very, is a very real one in that it’s much more difficult for folks to see the solidarity between each other.

[00:24:45] If you’re not also seeing directly the impacts of the economy, how the economy affects each other, unless it’s really wholesale in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, where I used to live when NAFTA. Was [00:25:00] passed it was something like 15 plants shut down and the town

[00:25:06] Jamala Rogers: And for listeners who uh, I just want to say sharpie for listeners who may not know Uh explain what nafta is north

[00:25:13] Shafea M’Balia: american free trade agreement Uh, and it’s an international trade agreement that took place between canada the united states and mexico to to play with um tariffs and taxes and and therefore development [00:25:30] Between and commerce between the countries.

[00:25:33] So it made it much easier for example for sledge lock You know the folks that make those locks in your door Well, they’d already moved from san francisco to rocky mount where they paid something I think somewhere around 16 18 an hour and they’d already moved to rocky mount where they paid folks something like 8 to 12 an hour you had people who Who who retired, you know make it no more [00:26:00] than 12 something an hour And so one day they came in and said, we’re going to move.

[00:26:05] And we’re moving to after NAFTA, we’re going to move, we’re moving to Mexico. And they said, well, why this is the flagship state, you know, the flagship plant, you make your money. They say, yeah, we make your money. We just want to make more. And so we moved to Mexico and where we can pay people eight to 12 a day.

[00:26:26] And so one of the things that we did was, [00:26:30] was to, um, you know, have some workers went down to Mexico and pass out leaflets. At the plant, the new plant, when it opened up, besides struggling around pay and terminate, uh, severance packages, we sent a delegation down to the plant in Mexico to explain to the Mexican workers what the plant was doing.

[00:26:52] And, you know, discussions with Workers in, in, in the United States about that is not the problem with the Mexican workers, the [00:27:00] Mexican where it was trying to eat, they just, they, there is the, it’s the company that is making the decisions and using us all like, like chess pieces. And so it’s a lot more difficult to figure out workers impact on each other because of the isolation, the smaller towns, you know, the greater distances, you know, the less compactness.

[00:27:26] Of neighborhoods, uh, and communities, [00:27:30] uh, with each other. And so that’s, you know, one of the things that, that are important. And of course, with the lack of history of, of unionization, folks, you have, we always have to do a lot more, there’s a lot more education that, that has to be done about what it means to have a union in the

[00:27:49] Jamala Rogers: workplace.

[00:27:50] And we’re going to definitely get to the role of education in a minute, Shafia, but you, when you were talking

[00:27:56] Shafea M’Balia: about the, how these plants pick, [00:28:00]

[00:28:00] Jamala Rogers: uh, sites that’s conducive to their self interest, and I remember, uh, the plant in St. Louis, at least the GEM plant, was built initially in a predominantly white residential area so that it made it accessible for those white workers to come.

[00:28:17] Over a short period of time, that neighborhood became predominantly Black. A lot of those workers were Black, and a lot of those workers also happened to be members of the Organization for Black Struggle. [00:28:30] So it made the plant facility accessible for protests, for a number of activities. So in a very short time, they said, We’re moving to Wentzville, Missouri, and Wentzville, Missouri is predominantly white and predominantly rural.

[00:28:47] It’s about 40 minutes away from St. Louis. So, you know, in other words, you Negroes won’t be on the sidewalks there because there are no sidewalks. So, uh, you know, when you were saying that, I’m like, oh yeah, you know, that’s definitely what we [00:29:00] saw happening here in, in St. Louis. And also when the other piece that you talked about was

[00:29:05] Shafea M’Balia: How

[00:29:06] Jamala Rogers: NAFTA, the role that it played in really undermining workers, you know, whether they be in Mexico or, or the South.

[00:29:17] But I also thought about the power of unions. Globally, when these kinds of issues come up, I’m like, you all, you said, talked about the way you all went there to [00:29:30] really, really, it was about solidarity. And as the world has gotten smaller, and the communications are a lot wider, we’ve been able to do that.

[00:29:40] And specifically, I remember just jaw dropping. Kind of response when I saw how doing the anti apartheid movement to see the the international longshoremen shut down ports But so I don’t you know, I don’t know that

[00:29:57] Shafea M’Balia: people understand like when you got that kind of power of [00:30:00] workers

[00:30:01] Jamala Rogers: And you got an issue that you’re trying to impact globally You got the power at home.

[00:30:06] That’s that’s to me just so inspiring.

[00:30:09] Shafea M’Balia: So we got to remember that

[00:30:11] Jamala Rogers: workers struck strikes and workers struggles all across the globe. We’re all connected because a lot of times it’s the same damn corporations that have spread their wings in other

[00:30:22] Shafea M’Balia: places. That reminds me of, um, the shot, the, uh, Charlotte Charleston, the Charleston dock work.

[00:30:29] [00:30:30] Oh yeah. What was that 20 years? Five. I think it was. Um, yeah, just about that time. Lieutenant governor was running, wanted to be governor and he was supporting this company who they wanted to build a non union port facility on somewhat near a facility. I think in North Charleston that Whereas the Charleston [00:31:00] port was, was organized, was unionized.

[00:31:02] And so a lot of folks don’t understand, like, for example, there’s a lot of black workers up in, up in, in, in, in dock workers. And it’s one of the few jobs that you don’t, you can feed your family without having had a quote unquote college degree. You can, might not even need a high school, I’m not sure. You can feed a family.

[00:31:23] You don’t have to have three jobs. They pay well and that’s because that’s only [00:31:30] because that there’s a union and it’s not has nothing to do with the, you know, the good graces of, you know, the whim of management. And, uh, so when the workers got, got wind. That, that, uh, this company wanted to build this other facility that would be non union, you know, they began to fight about that.

[00:31:49] Well, um, the state of, of, uh, Carolina, South Carolina, they made that a political and a criminal issue [00:32:00] by, um, arresting, you know, a numbers of workers, uh, uh, for demonstrating. The key, the key lesson that you were pointing out was the kind of solidarity. That happened as a result of them reaching out when other dock workers heard about what was happening first ILWU international longshoreman work longshore warehouse [00:32:30] workers Particularly local 10 on the west coast came in with a sizable donation for the strike fund And then the word was put out I mean they the brothers and sisters had the with the thinking to reach out to dock workers around the world And they were shutting down ports on the other side of the world in solidarity with the dock workers struggle in Charleston and enable them to win, to beat, you know, the state of South Carolina [00:33:00] and, um, and that company that wanted to set up now, of course the company going to try again somewhere else and they have, but, but they were not able to beat that solidarity.

[00:33:10] You know, when workers begin, we be, we begin to understand the power that we have. Um,

[00:33:17] Jamala Rogers: of, of just organizing and being in solidarity and being on one accord. You can’t do this if folks are all over the place in terms of, of solidarity. You, you gotta be of one of one mind and one [00:33:30] accord and, and thinking about that, I’m just looking at the, uh, it is been so encouraging to see the number of new formations in the south.

[00:33:38] that are responding to organizing, uh, the South. For example, uh, the Southern Workers Schools and Assemblies, uh, the Communiversity. Uh, tell a little bit about the Southern Workers Schools, because I know you all had a gathering back there in the spring, and I’m always just totally like, you know, uh, joyful when folks come [00:34:00] together, uh, particularly around workers struggles.

[00:34:02] And, uh, you all had folks from all over the South, you know, in those spaces. So talk about what came out of that and what you all are trying to do with those Southern workers schools and, and the assemblies as well.

[00:34:15] Shafea M’Balia: Well, the Southern workers assembly is a formation, if you will, a formation of, I, I, I’ll call it a new labor kind of formation.

[00:34:27] Cause it’s not, it’s, it’s made up of unions, but [00:34:30] it’s also made up of organizing committees and, you know, workplace committees that are not at the stage of, of being organized and committee yet, but just beginning to do the work and, and showing each other how to do the work, right. How to, how to, uh, you know.

[00:34:48] But both nuts in both kinds of organizing, as well as looking at, you know, the need for solidarity and how movement, how bringing in other workers from other workplaces [00:35:00] can affect and enhance the organizing that you’re doing. And so it’s kind of like it’s an educational and it’s a. Uh, vehicle, and it’s a way of breaking the isolation that workers across the South feel with each other.

[00:35:14] Now, union wise, kudos to national nurses union and to the United electrical workers union. Also, uh, ILA international longshoremen’s association, local 1422 out of Charleston. The same folks who did [00:35:30] fight. Back in the Charleston five that we were just talking about, and there’s a couple of other locals. Of course, Huey Local 150 out of North Carolina is a, is a major, uh, is a major player and bringing workers in.

[00:35:43] But those two, those combinations of education and breaking the isolation so that folks can build solidarity. So it played a role in, in bringing Amazon workers across the South together. They’ve, uh, they sit down and they bring, uh, try to bring [00:36:00] dock workers together, restaurant workers together. It’s really timely that we’re having this conversation because there’s a school is coming up next week.

[00:36:07] Uh, well, I don’t know when you’re going to add this, but, um, the weekend of. November 9th to the 11th. So, I’m not sure when we are airing, but there’s another school that’s coming up, and we know that Amazon workers are looking to [00:36:30] come through. And so, it also plays an incubation. Is that the word? As an incubator, incubation, I’m making up my own words

[00:36:42] Jamala Rogers: here.

[00:36:43] You putting something together and taking care of it, special care until it grows on its own. That’s right.

[00:36:48] Shafea M’Balia: There you go. There you go. And so, and so folks get to see and understand that they are not alone. That the issues that they think [00:37:00] are the worst in the world, my everywhere, you know, we go, it’s like everywhere I go, everybody thinks.

[00:37:06] That where they are is the absolute worst. And can nobody match ? Yeah. The problem that they have. And then they go meet somebody from another place or another workplace or another town and they’re like, uh, they’re talking the same, that’s worse, has

[00:37:22] Jamala Rogers: worse conditions than them. Right.

[00:37:24] Shafea M’Balia: You know, or more, you know, more horror stories and all the same kind of conditions.

[00:37:29] And [00:37:30] so, you know, we put, let encourage folks and folks get a chance to put heads together. And, and talk about things to do and things not to do, but also the need for building across the South so that a Southern movement of workers can be rebuilt to challenge local laws in the state or locally, uh, to come up with strategies, you know, just like the ruling class comes, has strategies that they [00:38:00] fight us with.

[00:38:01] Across the board, you know how they came up, you know, people thought, for example, that the right to work to starve laws just kind of organically came up in these different state assemblies. No, that was a coordinated action, you know, not just by the GOP per se, but also what is it the American Legislative Executive Council, Alec.

[00:38:25] That put together model legislation that these folks just [00:38:30] took to all of the different state legislators and all of a sudden popped up all these, these proposals, you know, as they have done in all both economically and socially, because, you know, these, these cultural and social laws affect us, us workers as human beings too.

[00:38:50] And so all of that is about, you know, keeping us off balance. Distracting on the defense on a defense and divided, [00:39:00] right. Um, and, and playing on, you know, the question of the racism that, uh, that, that, that gets fed. And when you talk about an incubation in terms of, of United States, you know, looking at it, playing people off and propaganda, twisting folks now around the, the Palestine piece.

[00:39:22] It is so, so insidious. Um, so we folks are able to start seeing and, and, and, and, and [00:39:30] struggling and, and ways of struggling around that and new ways of organizing. And so, you know, that is, that’s, um, you know, some of the things that the Southern Workers Assembly does and they do through the schools and they, they, uh, courage, the kind of organizing and communications that.

[00:39:51] You know, wouldn’t normally happen, you know, if we left into the isolation of our, our everyday, you know, go to work, come home, [00:40:00] you know, fall out, get up, go to work, come fall out. Yeah. Right. And do it all over

[00:40:06] Jamala Rogers: again. Yeah.

[00:40:08] Shafea M’Balia: So that’s, you know, that’s part of the Southern Workers Assembly in the schools. It was one last spring.

[00:40:12] I think that’s the one you were talking about. And I said, there’s another one coming up. You know, in the very near future. So, so Shafia, are these

[00:40:23] Jamala Rogers: places where campaigns emanate or campaigns are brought to the group for support or a little [00:40:30] of both? How does that work?

[00:40:32] Shafea M’Balia: Probably a little of both. I know that, in fact, I know that people bring campaigns.

[00:40:40] Right. And then some of also what happens is by virtue of folks coming together, they come up with, and there are proposals for campaigns, you know, to try to bring folks together. Uh, and so, for example, out of, [00:41:00] uh, maybe when was it a year and a half ago, there was the Southern Workers Power Program that got developed.

[00:41:10] And test it out. There was also before that there was the, um, PPE campaign during the pandemic, safe jobs, save lives campaign, particularly took off in North Carolina, but it was in other parts of the South, you know, which was a campaign [00:41:30] for getting protective equipment, a statewide campaign for workers to fight for protective equipment on their jobs.

[00:41:41] And Shafi, I think

[00:41:43] Jamala Rogers: people make an assumption that if you’re working somewhere, and this is what COVID illuminated for around a number of things, but particularly around worker conditions. And that is if you had a workplace, they automatically provided you with the gear [00:42:00] and mask and all that you needed.

[00:42:02] And I think what we saw was that that was not the case. And in fact, what we we’ve heard from folks on this show is that their unions. Provided them with masks and, uh, and all of that and the education around COVID. Are you finding that that was the case in

[00:42:18] Shafea M’Balia: the South as well? Oh, child, please. It was the, it was, it was a unions on and, or it was a Southern workers assembly to help either unions or workers [00:42:30] committees to fight for the equipment themselves.

[00:42:33] It wasn’t coming out of management. Shoot. I can remember working at the post office. And even just things before the pandemic and even such things as heat, excessive heat, which is of course with climate change, going to be a major issue, you know, for workers. Um,

[00:42:53] Jamala Rogers: in fact, that was one of the demands for the UPS workers who didn’t have air conditioning

[00:42:58] Shafea M’Balia: in their truck.

[00:42:58] That’s right. [00:43:00] That’s right. Well, I remember we didn’t have air conditioning. We used to hear about air conditioning, other trucks up north. And we like, How they got we down here in the south and we and it’s always at least 10 degrees hotter in this room than it is outside, whatever it is outside. And we, you know, we laugh because we said, okay, when are they going to come up with the excessive heat?

[00:43:23] Stand up talk. It’ll be when, you know, by the time they do it, it’ll be the fall when the temperatures get ready to drop. Right, [00:43:30] right, right, right. And you know, it never quite syncs up for black workers. Right. You know, so, uh, so yes, those, those are, they, they get generated, you know, from organization of the workers themselves responding to our own needs.

[00:43:50] It’s like, you know, we know what we’re doing. We, we are the experts at, you know, how things are carried out. We [00:44:00] are the, uh, what the essential workers and that, you know, you, you notice they hurry up and, and, and they kind of watered that down, you know, that, that the, the, um, the, the discussion of that so that people didn’t really, you know, they try to keep people’s minds off of the fact that you are essential.

[00:44:23] If you don’t want to, you’re not moving.

[00:44:28] Folks who were, you know, [00:44:30] cleaning the hospitals and cleaning the streets and, you know, turned the beds over at the nursing homes and kept the buses running and all those, those are essential jobs and those are where we are. And it’s funny, I have these arguments with, with folks who, who may be in other sectors of the economy who think, you know, uh, uh, black workers are, are we’re obsolete.

[00:44:55] I’m like, what? No, you don’t know where we are. It’s that [00:45:00] consciousness. That’s the part of the problem is that consciousness of where we are, what we do and what those jobs are and strategic value about. How to look at a overall picture to figure out how do we move together? That’s why that solidarity is important.

[00:45:21] That’s why that understanding the larger picture is important. Um, there was a gentleman came out with this book [00:45:30] called Labor Strategy. Oh, gracious. What he talked about was choke point. And looking at an industry where there are choke points in the economy. And that, um, and that if you identify where those choke points are, then you can have tremendous leverage about what happens.

[00:45:55] And therefore know where, if you know where to organize, when, you know, [00:46:00] when is strategic to make that move. Um, and, and, and so you don’t have to have. At least initially the majority of everywhere or the entire industry or the entire company. But you know, where, what is strategic to make that move? Where’s the heart?

[00:46:20] Where’s the, this, that, that makes the whole entity happen. And go organize that.

[00:46:27] Jamala Rogers: Exactly. And I’m thinking about that [00:46:30] term essential. And one of the things I know is that you all have found, uh, political and popular education to be essential to the development, uh, of workers and, and workers organizations.

[00:46:43] And, and, and I truly believe that because if you don’t have an educated, informed worker, you really, uh, just got somebody that’s going to be in the way. And I’m thinking about. When uh, there was a skilled trade union that [00:47:00] came to the organization for black struggle This is post ferguson because you know, everybody got some money to do something for you know The poor youth and so they created this program where they were looking for apprentices And uh, they came to us and say we got these, you know jobs is going to be number.

[00:47:19] Once they finish, they’re going to go skip the whole thing. They’re going to come right into the union. They’ll be making X number of dollars per hour. And we said, well, that sounds fantastic. Uh, we would like to see some kind of [00:47:30] political education as part of the training to do the skill that one of those days will be for political education around workers struggles, around workers history.

[00:47:39] Um, That was not a good idea for them. Um, and so we said that’s part of the, the, if there’s going to be a partnership here, that’s going to be a condition. And, uh, they, they refused to, uh, concede on that. So we, we pulled out. And so the power [00:48:00] of Uh, organized, informed worker must be pretty damn scary even inside of a union.

[00:48:06] So talk about like what you all have been doing at the communiversity and other spaces to really bring that kind of, uh, political education

[00:48:15] Shafea M’Balia: to workers. Well, I mean, educate, you know, I thank you for that, that, that lesson. I’m gonna take that one back. Right.

[00:48:26] I’m gonna take that one back. Right. I shamelessly, you know, [00:48:30] copy. Um, and pass on lessons. Um, no, no problem here. No copyright here either. We give credit now. We give credit. Mm hmm. Education has always been a real part of of BWFJ, um, history. We’ve done worker schools ourselves, you know, in the past. Um, I can think back, you know, of bringing folks in.

[00:48:55] Not just simply know your rights. You know, but how does the society work [00:49:00] and and what is it and what role do the workers play? So that we are conscious that we you know, we first of all that we have knowledge We have knowledge Right, you can’t figure out the choke point Unless you sit workers down and say, how does this work?

[00:49:16] Who goes? And you don’t want it. No, and how did they get there? And how did they get there? Right? Um, yeah, and then helping people put folks, you know, uh, uh, uh, put it put it all together. [00:49:30] Um, we did In the past, uh, BWFJ, uh, call international worker schools where we partnered up with, uh, international unions out of this one was, uh, uh, out of Germany and we did, uh, one for public sector workers, one for private sector workers, and then one for women with women and folks got to talk about their experiences and figure out, you know, and make connections with each other, [00:50:00] the communiversity.

[00:50:02] That is a newly developing, I’ll call it, partner, um, with BWFJ, um, is a combination of, um, of workers, activists, and labor scholars, black history scholars, um, working together to figure out, to do the education, to, to be the tool that we need. Workers need, uh, [00:50:30] their workers can use to further educate. So looking at the examples I just talked about in terms of the international school or the other kinds of workshops, other kinds of speakers, we’ve begun to do a series of, of, um, of webinars.

[00:50:46] And we’re trying to figure out the hybrid version, right. Of webinars and meetings that talks about the impact. Or and the effect [00:51:00] of black workers or a or the phenomenon of something on black workers So for example, let me let me make that real so right before the um, the teamsters Settled their contract, you know, we had discussion with teamsters on you know, what’s the impact of this?

[00:51:19] We found out that 20 of the drivers uh ups We’re black, black drivers were black workers. Well, we’ll see impact community. [00:51:30] What is the impact in a union? You know, what role could, should, uh, a black caucus play? What are the kinds of demands, you know, that are being raised? Uh, so we did that with, uh, with the teamsters and the teamsters black caucus.

[00:51:47] Then we did a second one that webinar was called how we move black workers and transportation logistics. And we put together bus drivers and, uh, UPS drivers [00:52:00] and, uh, Longshore. All of these are, is logistics and transportation, which many times people don’t think about. Right, right. You know, this, this stuff comes in.

[00:52:11] I

[00:52:11] Jamala Rogers: mean, if ever there was a strategy, that’s where it needs to be right there. Logistics. How, how is capitalism moving its goods and services and how to disrupt that? That’s right.

[00:52:20] Shafea M’Balia: So it comes, it comes from China. Well, how does it get into the country? You got young workers who unloaded onto [00:52:30] trucks, truck drivers who drive it, you know, to terminals to, you know, direct companies.

[00:52:38] And then you got, you know, retail and, and workers who then, you know, uh, unloaded at, at, at the facility or postal workers who move it. Move mail through. So, you know, it was a, you know, discussion, you know, very rich discussion like that. The second one we did mm-Hmm. was [00:53:00] on, uh, UAW and what does the UAW strike mean for black workers?

[00:53:06] And in that, we, we did a thing of where are black workers in general in the economy and where the auto, where is the auto industry and who’s the auto industry? Right. Um, so that and who does that effect? We just also did a piece, uh, with, um, a Palestinian American born [00:53:30] Palestinian worker and a woman worker who is, uh, on the ground coordinator for the stop cop city referendum campaign.

[00:53:40] And it’s the older folks who have to do with each other. Well, uh, the same ones who dropping them bombs are the same ones who come over here and they’re training folks in St. Louis. They’re training police in Savannah. They’re training police in Atlanta. [00:54:00] They’re training folks around the country on those same kinds of tactics.

[00:54:07] Right.

[00:54:09] Jamala Rogers: They’re connecting the dots and we have to do the same thing. So, so Shafia in the, in the few minutes that we have left, you talked about the, the Palestinian, and I know that this has been almost a divisive issue in our movement around the Palestinian question, but you all know, And you’ve spoken on [00:54:30] that.

[00:54:30] I think you might even have a statement of why black workers should be in solidarity with Palestine. Can you talk about how

[00:54:37] Shafea M’Balia: important that is? We’ve been talking all this whole conversation has been about solidarity, right? And how in isolation, you know, one of the major strategies of the oppressor is divide and conquer.

[00:54:53] Right to make me think that what was happening to you don’t have nothing to do with me, right? and [00:55:00] so You know, we just gave an example of what the idf the israeli defense force quote unquote defense force They’re over here training the police who use those same tactics on us in the streets Where y’all think that stuff come from that stuff?

[00:55:20] I mean, you know folks here I mean, they do have the intelligence I guess to make it up, but Here you got, I mean, a particular, [00:55:30] a particular methodology that is being exported and we need to know about that. You know, the oppressed also need to link up with each other. The same ones who are, Just as we’re talking about the police, the same ones who are, who have come up with that strategy against the Palestinians are the same ones who have come up with the strategy against us, who use it against, between us and indigenous folks, looking for [00:56:00] whatever, okay, you’re taller than me.

[00:56:01] You know, I got more gray hair to you. I wear glasses. You don’t. I mean, they’ll figure out anything that may be different to make us think that we should. In fact, I think about the reparations movement. I know this is not about Palestine per se, but you’ve got something that’s developed around reparations where you got some folks talking about, well, we don’t need to talk about folks who can’t trace their history back to, uh, before 1865 in this [00:56:30] country.

[00:56:30] Well, that’s You know, imperialism, capitalism is worldwide and they playing chess game and playing chess and we the pawns. And so we’ve been, you know, arguing about whether or not we should be in solidarity with Palestine or we should be in solidarity with, you know, Trinidadians fight for reparations or Palestinians fighting against, you know, for their own country back.

[00:56:55] And they’ll use that as a way for us not to understand [00:57:00] that we are also paying for that. It’s our money that is paying for those bombs that are being dropped. But we ain’t got no health care. We got folks sitting out. I mean, homelessness is increasing exponentially, you know, across this country. And nobody, and that’s not being addressed.

[00:57:21] And when we raise it, they’re like, they ain’t got no money, but they throwing money at Ukraine and Palestine. Like, Oh. [00:57:30] At israel’s already getting three three billion a year plus

[00:57:34] Jamala Rogers: Deep deep pockets. They keep on finding money. Yes.

[00:57:37] Shafea M’Balia: Yes. Whoa. Yeah Here we go. Yeah, they get three billion dollars a year and they was claiming that they didn’t have money They weren’t getting basic supplies for their soldier.

[00:57:48] What y’all doing to money? Right with

[00:57:51] Jamala Rogers: that not not three million three billion with a B

[00:57:56] Shafea M’Balia: And now these jokers gonna go back And they talk about to [00:58:00] this day today. I know again, we won’t air this today, but today, uh, we’re taping this on. What is it? November 3rd, they just passed in the house. I think it was 14 billion more to give these folks and they want to do it in a way that they don’t even have to account.

[00:58:22] Right? Mm-Hmm. , right? So again, we ain’t got no healthcare. We got folks being put out on the street [00:58:30] and being made to be criminals to survive around, you know, across the border, like chess pieces, like, and have know, and then, and then playing folks off against these other, you know, thousands of folks. Ain’t nobody already ain’t got no healthcare.

[00:58:47] Ain’t got no housing, and you got folks in the street. And the folks who are living there already said, well, we ain’t got no housing and here you go, you got, you know, 10, 000 immigrants who are coming, [00:59:00] you know, what else going to do, how come we can’t, you know, how are we giving housing to these people when we ain’t got housing.

[00:59:06] And so it gets to be, you know, they’re playing people off against each other, as opposed to the ones who are making the policy in the first place. And so, you know, those, those economic reasons, those, those political reasons, those moral reasons. Right? Yeah. Those, those

[00:59:27] Jamala Rogers: are all, all of the

[00:59:28] Shafea M’Balia: above. Yes. All of the above.

[00:59:29] [00:59:30] Yes. It’s like they bombed in, in, uh, what is it, in the eighties, in Philly, and they dropping bombs and killing babies, you know? Uh. And old people, you know, in Israel now and ain’t nobody supposed to say nothing. Right, right.

[00:59:48] Jamala Rogers: Well, we certainly have, have explored a number of issues. We’ve been all over the globe.

[00:59:56] But Shafia, we just scratched the surface, right? [01:00:00]

[01:00:00] Shafea M’Balia: We just scratched the surface.

[01:00:01] Jamala Rogers: It’s so much that’s happening and is potentially going to happen when it comes to workers rights, particularly Black workers rights. We thank you so much for taking time out of your busy organizing schedule to join us on

[01:00:15] Shafea M’Balia: Black Work Talk.

[01:00:18] So thank you so much. I’d love to do it again. We got to hang out some more. I’m going to get you on one of ours. So we can share. And um, [01:00:30] You know, share the work that y’all are doing. OBS. St. Louis. And the solidarity between both, you know, the workplaces, the organizations, the communities, you know, we are one.

[01:00:42] Jamala Rogers: That’s right. That’s right. So we will, uh, stay in tune if there’s issues or, or events that are happening. We’re going to, uh, get them out to, uh, folks that they know about it and participate with, especially the ones that are virtual. So you can be anywhere in the world. And participate in that. But again, thank [01:01:00] you.

[01:01:00] And, uh, continue to struggle, continue to solidarity. Uh, and

[01:01:04] Shafea M’Balia: we’ll talk soon. Yes, ma’am. Thank you so much.

[01:01:11] Bianca Cunningham: I thanks to Shafia Mbele for joining us today. Black Work Talk is published by Convergence, a magazine for radical insights. If you haven’t already subscribed, be sure to do so to catch future episodes when they drop and leave a review wherever you listen.

[01:01:26] You can support this show by becoming a monthly patron for as [01:01:30] low as 5 per month at patreon. com slash black work talk. Executive producer for Black Work Talk is Xiomara Copeno, and Josh Elstro is our producer. I’m Bianca Cunningham.

[01:01:42] Jamala Rogers: And I’m Jamilah Rogers, co host. Thank you for listening

[01:01:45] Shafea M’Balia: to Black Work Talk.