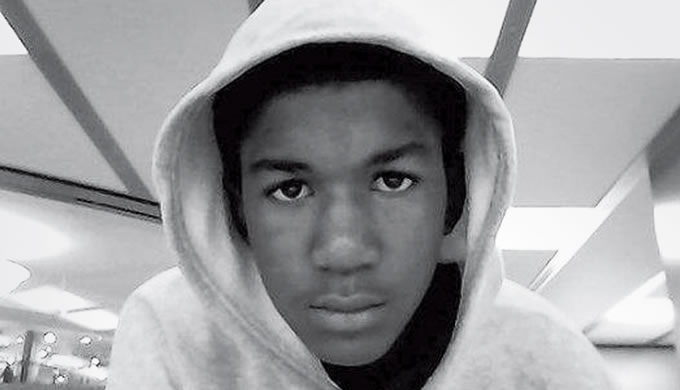

It has been almost four months since George Zimmerman got away with murder. I started writing this post back then, but was so overcome with emotions that I couldn’t articulate much more than what was on our placards as we marched across the city in protest: “Justice for Trayvon Martin.” And then, inwardly and in small groups of friends, colleagues, and students: “Not again.”

Because this was an “again.” It was another moment in American history where the message to Black people, Black youth, and Black young men in particular was “YOUR LIVES DON’T MATTER.” My unshakable belief in human goodness, despite so much evidence to the contrary, first led me to believe that this would be a moment where the racism that continues to permeate and define American culture would be so obvious, so egregious, so up front that people wouldn’t be able to deny it. That we would have to have an honest conversation about not only overt acts of violence, such as Zimmerman harassing, provoking, and ultimately murdering an unarmed boy, but the systemic racism that is felt through our court system, police force, and local and national governments.

But that’s not what happened. Even after the President gave an impromptu news conference, naming racism and what it feels like in America, acknowledging that he, arguably the most powerful man in the world, could have been Trayvon Martin. He, who was voted in to office by not just Black people in this country, but the majority of the voters. And still, much of the country was in denial about it. Continues to be. Sometimes feels like always will be. And it felt hopeless.

So I did not write about it, outside of the message I sent to my students who organized the Trayvon Martin fundraiser the year before. Outside of the email I wrote to a family member, in response to racist propaganda she sent me in the days afterward. But I did a lot of talking about it. While marching through the streets of Manhattan last summer, so many of us turned to each other, almost speechless with grief and rage, and said “I’m here because I don’t know what else to do and it’s too much to be alone right now. But it is not enough.” That’s how I felt about writing. It’s not enough. I felt like giving up—and I’m not even the target of racist violence the way that many people in my community are. But one of the benefits of my job is being inspired by youth. And as a teacher, I do not actually have the luxury of giving up. Not for long, anyway.

As a white teacher of almost exclusively students of color, I think a lot about my responsibility of being an anti-racist ally and a caretaker of my young people. I do what I often do when I come up against something in my teaching and can’t figure out how to respond: I turn to my students. So it is with deep gratitude for them and the rest of my school community that I finally find the words that I have been looking for since July, and to share this story with you about the day my Crew kicked it with Peggy McIntosh and her 1989 article about the knapsack.

****

Alice walks in late, a stack of papers in one hand, and a small bag of office supplies in the other. She throws down her bag and starts stapling furiously, enlisting two other students to help her.

“Sorry I’m late, Rachel. Class ran over, and I didn’t have anything prepared and I dropped my phone on way back from yoga and …” Her voice trails off as she goes back to focusing on her task. I wave off her angst and grab a stapler to help her create her article packets. It is student-led discussion day, where they are required to lead class with a text of their choosing. This particular student, a fiery young activist whose consciousness was blown open this year by Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow, did not turn in her outline in advance, but told me she was going to be talking about race. I looked down as I stapled and saw what she chose: Peggy McIntosh’s “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack.” I smiled and looked up at her. I hadn’t read it since my college days, and I was curious of where she would take it and how the other students would respond.

Alice began reading, and it took a few moments for the students to settle in. Reading the introduction, where McIntosh talks about her work in Women’s Studies, one of my students sucked his teeth and rolled his eyes. Alice ignored him and continued to read in a strong, clear voice: “Thinking through unacknowledged male privilege as a phenomenon, I realized that, since hierarchies in our society are interlocking, there was most likely a phenomenon of white privilege that was similarly denied and protected.” Some of the students groaned.

One spoke up: “There she goes again …”

I re-direct: “Who do you all think this article is written for, after reading the intro?”

Emmanuel answers quickly: “Ignorant white people. Why do we have to read this?”

“Stop being so ignorant and keep reading,” replies Alice.

He sighs heavily. “Girl … fine.” He clears his throat, “As a white person …” He stops reading and looks up over his glasses, eyebrow raised.

“It’s fine, Emmanuel, we know you’re not a white person. Keep reading.” I say.

He laughs and returns to the paragraph: “… I realized I had been taught about racism as something that puts others at a disadvantage, but had been taught not to see one of its corollary aspects, white privilege, which puts me at an advantage …”

As we continued reading, the students became really quiet. There’s this energy that comes over the room when my students are really taken in by something. I watch them as they devour the material, eyes glued to the paper, voices loud and clear as they read. When they stumble over a word, they don’t just keep pushing forward like they do when they’re embarrassed, but take the time to pronounce everything right, their peers jumping in if they need to, to make sure that nothing gets lost in the translation from page to voice.

When we started reading the list of white privileges, at first they gave me quizzical looks. As we read on, they started nodding their heads, adding stories and anecdotes about when they experienced them (#17, 21, 33; it went on). For a significant portion of the class, we were all hysterical (#40: choosing public accommodations. One of our students told a story about when he and his after-school youth media program stayed in a hotel in a small city in Pennsylvania. When they came down to complain about their broken TV and tub, the white man behind the counter told them they were probably the ones that broke them, and to go back upstairs and leave him alone. The students’ ideas for how he should have responded got really creative and had us literally gasping for breath, we were laughing so hard).

There were many points where the students continued to laugh, like #46: flesh-colored bandages. They were like, “This sh*t is funny, but it’s real, Rachel.” Yeah it’s real. And though we were laughing and joking about it in that room, I am reflecting on it now in light of many conversations I have had with my family members and people from my almost 100% white home town (Southeast Michigan: that sh*t’s real) about race and the Zimmerman verdict. And how not funny any of the 50 facts that Peggy McIntosh lists really are. How they are a byproduct and reinforcement of the world we inhabit, and this world allowed a young man to be murdered, with his killer receiving no consequences.

Towards the end of class, my student Jordyn asked me: “Rachel, how come some white people get it, but most of them really just don’t?” I thought back to the year prior when I took my students ice skating at Bryant Park, and Kemia, a direct and assertive young woman, was standing really close to me as we walked down the street. I tried to make a joke with her: “Honey, you live in the South Bronx. How are you walking around in Herald Square clinging to me like you’re my child?” “Because, Rachel. When white people bump into you, they don’t say excuse me. It gets me so pissed and I don’t want to ruin my day. I paid $11 to come on this trip.” I put my arm around her shoulders and we walk to the rink together. It may seem like a relatively benign example, especially if you are living in New York City where you are jostled many times a day as you rush from one obligation to the next. But the way it made her shrink, her shoulders slumping forward, her head slightly bent, anxiety in her voice and her gait—it was not benign. It was so very heavy.

McIntosh’s analogy of a knapsack works: White folks are carrying around a whole bag of goodies and privileges that they were carrying since they left the womb (as my brother puts it, “White people are born on third base, and walk around thinking that they hit a triple!”). A whole bag of keys, access cards, get out of jail free passes, and other goodies that open doors, keep them on the flip side of the power structure, and allow them to walk willfully ignorant through their days if they choose, never having to think twice about racism and its legacy. They can use what’s inside their knapsack to shut people of color down by telling them they are pulling out what they perceive to be in their knapsack: that pesky little “race card” that they pull out when they try to have real talk about policing, job discrimination, the hypersexualization and objectification of Black women’s bodies (Miley Cyrus, anyone? Oh wait, I’m beyond tired of talking about her).

And then there’s the other knapsack. The heavy-ass one that Trayvon Martin and every other young (or old or middle aged or any) Black person has to carry through their lives. Weighed down heavy with historical and present structural and more personal racisms. Red-lining and intergenerational transfer of wealth. Guilty until proven innocent. Suspicion and rage and code switching and all the other things they need to carry with them to survive in a largely white-owned world. For young Black men, this heavy-ass knapsack of racism they are forced to carry often ups the consequences of their actions. Like how drug use rates are the same across race, but Black people are disproportionately incarcerated for their use.

I think about W.E.B. Dubois’ The Souls of Black Folk, and his description of the double consciousness, written back in 1903, and how the words still ring true, more than 100 years later:

“It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his two-ness—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

I think of the heavy-ass knapsack Trayvon was forced to carry in his short human life. I think of how the media turned the Zimmerman trial into the Martin trial, how it became about Trayvon’s guilt or innocence. I think of how my boys are weighed down so heavily with the burden of historical and present structural racism, and the extra knowledge they have to carry and the extra risk they have to face to just do what most teenagers do: make bad choices and get into some kind of trouble (and get into trouble even when they are NOT getting into trouble).

What would their lives be like if their mental, physical (you can see it in their bodies, their walk, their eyes), spiritual, and emotional space was freed up by not having to carry that heavy-ass knapsack? I wish this for my youth so deeply. And these are adolescent boys. White people: can you imagine carrying that around with you? All the time? Your sons/brothers/self having to be aware of that, all the time, and hold it on your just broadening shoulders? The consequences are so great, not just for their individual lives, but for our collective experience as a country, a world. Returning again to Du Bois:

“Through history, the powers of single black men flash here and there like falling stars, and die sometimes before the world has rightly gauged their brightness.”

Where would we be as a nation if we did not lose so many bright stars, either in body or in spirit, before they reached their full actualization?

All this I’m thinking about as I struggle to answer Jordyn’s question: Why do so many white people just not get it? I don’t remember exactly what I said that day. But I am thinking about an email exchange I had just last week with Alice. She earned a scholarship and went away to college. We were chatting about how her classes were going, and how she was liking school in general. She wrote to me about her African-American Studies class and all the books she has been reading, and then described her fellow students this way:

“I love the people here—correction, the people of color here. They are like family. As for the white people, some are cool but others are so ignorant. I mean, it could be worse. But I think we’re finding ways to improve it.”

I chuckled to myself as I read it. One, because I can totally hear her voice and see her face as if we were talking in person, and two, because I had just returned from a conference where I was having very similar thoughts. It was a gathering of educators who had really solid pedagogy, but lacked a depth of race and class analysis that I found deeply troubling. At first I was kinda bummed thinking about this: how from one generation to the next, not much seems to change. But as I reflected more, I replied to Alice:

“What’s cool about college is that because many students are really open to new ideas and having so many new experiences, the possibility for change is very present. It takes personal commitment from people, and as we see in our country, a lot of white people choose not to do that work. But some do. And you will find each other. And hopefully become important allies in justice work.”

And this gives me hope. The staff at my school gives me hope. The many tireless activists in my two homes, Detroit and New York City, who are doing amazing things that many woul