“When I hired into the University of Massachusetts Amherst Labor Center as director in 2018,” Cedric de Leon said, “I wanted to bring a vision of intersectional solidarity, one in which the struggle for economic justice is inseparable from the fight for gender equity and racial justice.” He began thinking about what this would look like in practice and searching for examples. But he found that historians who center Black workers had produced very localized studies—books like Robert Korstad’s Civil Rights Unionism, about FTA Local 22 and the Black women who led the tobacco workers in North Carolina, or Robin D.G. Kelley’s Hammer and Hoe, about communists organizing in Alabama. “They’re fantastic studies,” he said, “and I thought to myself, ‘There’s got to be Black mass organizations that tried to nationalize this struggle. What are they?” When he found them in the historical record, he decided to write Freedom Train, which is under contract with University of California Press.

De Leon has written three previous books and numerous journal articles. His work is informed by his experience in the labor movement as a researcher, organizer, rank-and-file member and elected officer. Steven Pitts, creator of Convergence’s Black Work Talk podcast and the associate director emeritus of the University of California Berkeley Labor Center, sat down with De Leon to talk about Freedom Train in depth. They had a rich conversation. This is a small slice of their discussion.

Steven Pitts: Let’s start with one, two or three major elements of the book you would like people to know about.

Cedric de Leon: One thing I show in the book is the inconsistency of white trade unionists and labor activists, including progressive ones, in advancing the cause of interracial labor solidarity. We’re told that folks in the CIO and the Communist Party were unapologetic about their advocacy of Black labor, but what we see in fact is that the record is uneven. And by contrast, Black folks, and in particular, the independent Black labor organizations that they founded, were not only more consistent, but they were really the vanguard of the struggle for interracial solidarity. So that’s the first thing.

The second piece is that I really wanted to move beyond this academic tendency to prove or demonstrate Black agency by just showing that Black folk were around, that they were present at their own liberation. And I just think that that’s kind of a thin account of Black agency and Black efficacy. What I tried to show in the book is that Black folk cared enough about integrating the labor movement that they disagreed about it. And also, by the way, they occasionally aligned with one another and put aside their disagreements for their own tactical and strategic reasons. I think that’s a far richer account of Black agency. These are not all just settled questions: How do we get the institutionalized labor movement to not only accept Black members but also accept Black leadership? These are not easy questions, and people disagreed vehemently about how to pursue those goals.

So that’s the second piece: I wanted to show a little bit of the flavor of Black factionalism. I want people to see not just the consensus, but also the conflict within the Black community over these issues.

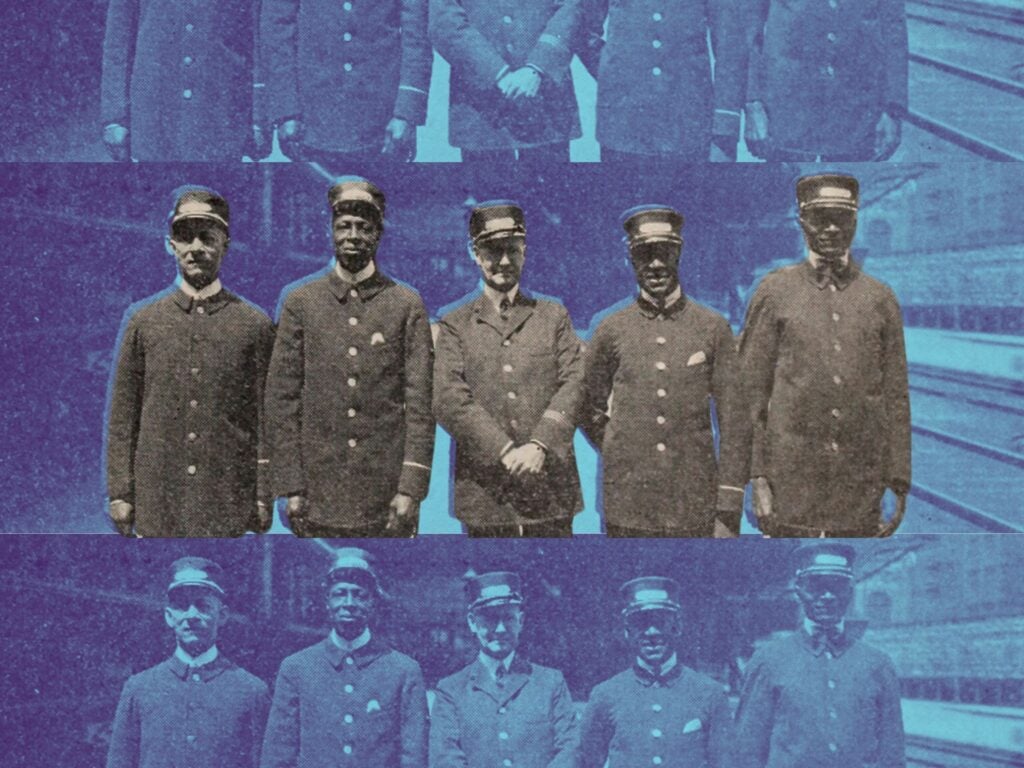

And I suppose if I had to pick a third takeaway, it would be the role of Black women. And in particular, the growing influence of Black women in the in the struggle for interracial solidarity. They’re basically absent in the beginning of the book where I’m writing about the African Blood Brotherhood and the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP). The Black women are part of the leadership in Harlem for the African Blood Brotherhood. And there are a number of women’s auxiliaries throughout the BSCP who are active and doing important work for that union.

But I would say that Black women grow in influence in the National Negro Congress (NNC) in the 1930s and early ‘40s, especially with the leadership of Thelma Dale. And I would say like the high point of Black women’s involvement in this struggle was with the National Negro Labor Council in the 1950s, when Vicki Garvin is really part of the top leadership of that organization. I would be remiss if I if I didn’t at least mention the throughline of Black women’s leadership throughout the struggle.

Black workers help grow the CIO

Steven Pitts: I thought the idea that Black leftists were actively engaged in organizing Black workers to support the formation of core CIO unions is really important. Because oftentimes what happens in the popular kind of storytelling is we have some discontent, and a sit down in Flint. Then all hell broke loose and all of a sudden we have massive union density. That’s the short version of the story, right? But there is no real sense of the hard work…the organizing that took place to achieve the successes. So give me a sense of the actual work itself because it’s an amazing story.

Cedric de Leon: The work that the National Negro Congress did was absolutely pivotal. It’s a story that is not told about the massive growth of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) in the 1930s because the CIO did something that was important, at the prompting of Black trade unionists. which was to say, we’re going to decide what the strategic sectors are that we’re going to organize. One of the arguments that they made was that in order to actually push the industrial union movement forward and extract massive concessions from capital in this moment, we need to hit capital where it hurts, and that is in steel and in auto, especially steel. These sectors of the American economy were sectors in which Black folks were disproportionately concentrated. Because it was dirty work. It was hard work.

White folks were concentrated in the trades, in skilled trade positions, even in auto plants. The folks in the foundry, the people who are doing the so-called unskilled work on the line, and so forth, were Black people. And so the question was, “How are we going to reach these Black workers? And how are we also going to prevent the boss from dividing the Union by race, which they had done to dramatic effect in the 1919 Great Steel Strike?”

And what [NNC Executive Director] John P Davis did was basically hector every major league leader of the steelworker organizing campaign, Van Bittner, John Brophy, you know, Phil Murray, all these cats. John P. Davis would like go to cities where he knew they were going to be, go to the hotel where they were, and just buttonhole them, and give them a proposal and say, “Look, let me explain to you what the steel industry looks like in various parts of the country. There’s parts of the country, places like Birmingham, Pittsburgh, Gary, Chicago, where most skilled workers are Black. Let me ask you a question: John Brophy, tell me Phil Murray, how do you get to these people? How do you then organize them? Well, before you answer I have a proposal for you. Give me the resources to hire Black rank and file steelworkers as staff organizers, and let us organize the steel industry for you.”

And it’s just genius. Some of these organizers who Davis recruits are just incredible. And by the way, the rank and file were ready, especially in the context of the Depression and so forth but, by one account, Steel Worker Organizing Committee “lodges,” as they were called, grew like mushrooms all over the country because of the partnership between the NNC and the CIO. There are a ton of internal documents talking about the very tight coordination between Davis and the NNC cadres, and the CIO.

This happens in other industries as well where Black people are disproportionately concentrated, industries such as tobacco, meatpacking and auto. In meatpacking in the Gary-Chicago corridor there are 14 locals that that are formed in the span of just three years, and nine of the 14 locals are headed by Black workers. This is the work that the NNC does. We’re talking about hardcore one on one organizing, organizing committees, cadres, it’s striking for recognition and first contracts. They do this all over the country. And the unsung heroes of that campaign, who I think were central to the massive growth of the CIO, were Black workers and Black labor activists like John P. Davis.

Black united front wins first step to fair employment

Steven Pitts: It seems to me from reading your book and knowing things about the period that the biggest growth in terms of both Black local organizing and Black left power came when folks formed an organic, legitimate, broader coalition, a Black united front.

So this whole notion of what’s important to building power is [the] united front and a key challenge is holding the coalition together. You had a rich discussion of one of these united fronts: the March on Washington Movement of the 1940s. Tell me more about it.

Cedric de Leon: Right. So [Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters organizer and President A. Phillip] Randolph was president of the NNC and resigns at the 1940 annual meeting because he believes that the Congress had been basically infiltrated by the CIO and the Communist Party. So he decides to basically go back to his post and devote himself full time to the BSCP. But as he returns to the sort of workaday tasks of that job, he realizes that his membership is upset about still another set of issues, the exclusion of Black workers from the defense industries and by association, the unions who represent the workers in those industries, and also the segregation of the armed forces.

And he’s pulled into these successive meetings at the White House, to deal with this issue, and those conversations go nowhere. And he’s saying, this is not enough. It’s not moving the needle. I think what we need to do is bring is bring thousands of Black folks to Washington, DC, and pressure the New Deal administration to desegregate the defense industry, really desegregate industry, labor and government.

And to make a long story short, he is able, under the pressure of that mass demonstration, to push the Roosevelt administration to sign Executive Order 8802, which prohibits discrimination in the defense industries and also establishes a Fair Employment Commission to basically bring to heel anybody who runs afoul of this executive order. And it was hailed at the time as the first major government measure that made an appreciable difference in the lives of Black working people since Reconstruction. Once he’s able to secure this executive order, he then calls off the March on Washington.

Steven Pitts: How did non-left elements of Black civil society relate to the March on Washington Movement?

Cedric de Leon: The rough pattern is that whenever the left and liberal factions in Black labor work together, the other elements of Black civil society—the press, the clergy, the NAACP, in the Urban League, and the fraternal organizations—are part of the coalition too. But when they break, typically what happens is that the bulk of Black civil society, with the exception of the intellectuals, goes with Randolph pretty much every time. And so, you know, in this case, the NAACP is very deeply involved in the March on Washington movement in 1941. And in fact, it’s [NAACP President] Walter White and Randolph in the Oval Office with President Roosevelt. So the NAACP especially plays a leading role.

Steven Pitts: I want to close with another important chapter, and that’s the role of Black labor leading up to the March on Washington in 1963. That’s a story not usually told. You know, I think that for a long time, the story was just that Martin Luther King summoned folks to DC and gave a speech about a Dream. What’s still not fully recognized is the role of Black labor in turning out a quarter-million people, and the presence of economic issues as central demands. So give us a sense of what’s happened in terms of Black labor in the late 1950s and early ‘60s, and the role Black labor played in the build-up to the March on Washington in 1963.

Black labor moves the 1963 March on Washington

Cedric de Leon: The story that typically does not get told is that actually the people who will organize the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom were in the Negro American Labor Council. The moving spirit behind it was, once again, A. Philip Randolph and his lieutenant who was once a member of the US Young Communist League, Bayard Rustin. One thing that’s significant about that is that it was the first time since the National Negro Congress in the 1930s where the liberal and left factions of Black labor unite. And so they do so first to try and push George Meany, president of the AFL-CIO at that time, and the leadership, to enact stringent punishments for those local and state affiliates who continued to practice racial discrimination in their unions. They tried through internal channels, but also acting out at executive committee meetings and also national conventions, and they were not able to make that happen.

Also, even though the liberal and left factions are sort of cooperating in the Negro American Labor Council, they’re fighting with each other inside the council. And so there’s a militant wing that is just sitting there thinking they keep coming to these conventions, they’re organizing on the ground, and nothing is changing. And at this point people start to talk about doing militant direct action. Joe Overton in New York specifically says, “Why don’t we do a march on Washington?”

But nothing really happens until Randolph talks to Bayard Rustin in early 1963 and basically asked Rustin to formulate a plan to do an actual march on Washington.

The pivot there, strategically speaking, is to see if they could accomplish legislatively what they could not do internally within the labor movement. Could they get the federal government to impose anti-discrimination laws onto the labor movement, industry and the rest of government? And the reason they did [was] because African Americans were once again facing a crisis of unemployment and underemployment, something that Dr. King spoke about extensively. That was the pivot. Could we now, to your point earlier, work towards pressing the state to do what we need them to do so that we can be members and leaders in the labor movement?

It turns out that that tactic was able to push organized labor to impose civil rights discipline on their local and state affiliates to the point where the State Feds [state federations of labor unions] of Alabama and Mississippi actually find themselves lobbying on behalf of the civil rights bill in 1964. The March succeeds so fantastically that organized labor is simply embarrassed to not cop to Randolph’s line. And so [AFL-CIO President George] Meany imposes civil rights discipline on his local and state affiliates.

And simultaneously, the mass pressure from below scares enough white elites in Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is passed by the Senate, because [the Negro-Labor Alliance] now threatened a national one-day strike if they didn’t pass that and tried to filibuster in the Senate. These are just titanic victories. And as you say, the sanitized version of the story is Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

But what we don’t hear about is Black labor’s leadership in this moment. Because as a matter of fact, the NAACP and the Urban League are resistant to joining the March. They declined to endorse the March and it’s only in July that the NAACP and the National Urban League signed on as co-sponsors of the March, because they are worried once again about jeopardizing the relationships with white elites on Capitol Hill. The SCLC was doing really important work doing voter registration and desegregating public spaces in the South. They were not really focused on the March on Washington. It was the Negro American Labor Council, Bayard Rustin and A. Philip Randolph, who really were the masterminds behind this magnificent triumph in American labor history.

Steven Pitts: Cedric, I am really glad to have finally sat down and talked with you. This was a wonderful conversation and there is so much more in the book I wished we could have dug into. There is a lot here. It makes a valuable contribution to better understanding the historical interplay of different strands of Black labor activism and their collective impact on the Black Freedom Struggle. I hope folks will pick up the book, digest it, discuss it, and explore how to apply lessons to this current moment of rising activism. Be good, man!

Featured image: Pullman Porters and a conductor, 1920, from the Baltimore and Ohio employee magazine. The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, which was organized in 1925, played a vital role in both labor and civil rights organizing. Image from the Flickr Commons.